Main Menu · Search · Current Issue ·Contact ·Archives ·Centennial ·Letters to the Editor ·FAQs

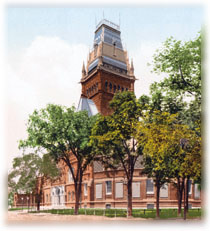

By the end of 1999, Memorial Hall will look much as it did in this view from a period postcard. |

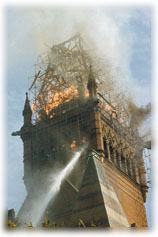

The tower of Memorial Hall, truncated by fire on September 6, 1956, will finally boast a spire once again. Construction begins on site July 1, and the building will be whole by year's end.

The hall sits just north of the Yard. "Looking sawed off, squatty, meaningless, the present stub of a tower can be seen from various places in the city," says Charles Sullivan, the longtime executive director of the Cambridge Historical Commission. "Restored, it will be magnificent, a visual landmark in the best sense, one that people will give directions by."

Even more loftily, the soaring spire may be seen as a symbolic exclamation point at the closing of the century and of the University Campaign.

Architects CBT of Boston have done their drawings. Harvard has ordered the steel for the frame. Contractors will build it off site in nine pieces, which truckers will transport to the hall, where a crane will hoist them up, to be bolted to the existing tower belfry and to each other-- this phase taking a month. Workers will construct a cantilevered platform encircling the top of the belfry, erect scaffolding, and put in place the red, green, and black slates--this work requiring three months. Finally, up go the sandstone pinnacles and the prefabricated dormers, the finials, the eight-foot-high balustrade with its filigree and foliation, and the weathervanes, all of copper. The spire will be 58 feet--five stories-- high to the top of the balustrade, says project manager Elizabeth Randall, and, counting the vanes, will reach an altitude of 210 feet, 6 3/4 inches, above ground --a full three-quarters of an inch taller than William James Hall.

The restoration will not replicate the spire that burned in 1956. That version had four clock faces, as well as a booming bell.

The desecration Byron Blanchard |

Memorial Hall has had three different spires. The first was covered in polychromatic slate but was otherwise quite plain. When the building was virtually complete, in 1876, the architects--Henry Van Brunt, A.B. 1854, and William R. Ware, A.B. 1852, S.B. '56--began to hear criticism that the spire was too plain. They were permitted to revise it. Within two years, the spire acquired four narrow dormers and eight crocketed finials that echoed the corner turrets. (This second spire is reproduced on page 63, from a postcard of the period.) The clocks and bell came in 1897, a reunion gift from the class of 1872. Van Brunt accommodated them, replaced the slates with copper sheeting, and reforested the spire with 16 finials. During World War II, Harvard stripped the spire of shaky decorations and replaced the eroded copper with tarpaper. It remained thus denuded until President Nathan M. Pusey and the Harvard Corporation authorized its restoration. Just as this work was nearly done, the spire caught fire, allegedly the victim of a worker's unattended blowtorch.

As Memorial Hall neared its centenary, signs of institutional indifference to its overall well-being, inside and out, were evident. This magazine devoted its March 1972 issue to the building's plight. Art historian Daniel D. Reiff '63, Ph.D. '70, wrote that the Ruskinian Gothic edifice was "unique in this country" and a "wonderful antidote" to featureless new construction everywhere to be seen. Historian Walter Muir Whitehill '26, A.M. '29, reminding readers that the building is, before all, a memorial to Harvard men who died fighting for the Union in the Civil War, argued with some outrage that the neglect of the structure was "a sorry example of the shortness of human memory" and declared, "It's high time something was done about it."

Something was, in the fullness of time. Well-wishers rejoiced in a major renovation of the building's interior and exterior in 1987-88 and celebrated further in 1996 when the vast "nave" was polished up with the aid of $12 million from the Annenberg Foundation and returned to service as a dining hall. Still, there sat that truncated tower.

In the 1980s, Robert G. Neiley '43, a Boston architect and member of the Cambridge Historical Commission, was in charge of Memorial Hall restorations. He was asked to draw plans for replacing the spire, the copper-clad one with clocks (see "The Missing Tower," May-June 1988, page 54). But which spire to build was not formally vetted at the time, says David Zewinski, associate dean for physical resources and planning. Neiley's view is that the clock spire "was too heavy visually. It was overkill. The tower now proposed is just perfect."

The decision to restore the second tower instead of the third was made by President Neil L. Rudenstine and Jeremy R. Knowles, dean of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences, with the advice of architectural historians. The rationale for the choice is that the slate version of the spire reflects most accurately the architects' original intent. Lacking expanses of copper and clocks, tower number two is also cheaper to build and maintain.

The project cost will be $4 million. About $2.5 million has already been given specifically for the restoration of the spire. Some of this is in a fund established in 1981 by Abram T. Collier '34, LL.B. '37, AMP '52, to which others have contributed. Katherine Bogdanovich Loker has made two $1-million gifts for the purpose. Earlier in the University Campaign, she funded the transformation of Memorial Hall's basement into Loker Commons, an undergraduate gathering place.

Says Charles Sullivan, "It was an amazingly generous act by Mrs. Loker and the University to undertake to replace the tower of a building that University administrators wished at one time would go away entirely."