![]()

Main Menu · Search · Current Issue · Contact · Archives · Centennial · Letters to the Editor · FAQs

![]()

Main Menu · Search · Current Issue · Contact · Archives · Centennial · Letters to the Editor · FAQs

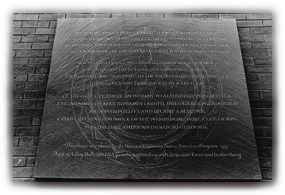

A handsome plaque on Matthews Hall, unveiled May 3, marks the site of Harvard's Indian College and salutes its first scholars. Photograph by Kris Snibbe A handsome plaque on Matthews Hall, unveiled May 3, marks the site of Harvard's Indian College and salutes its first scholars. Photograph by Kris Snibbe |

In an affecting ceremony on a chill, inhospitable morning in May, more than 300 people gathered by the southeast corner of Matthews Hall in Harvard Yard to witness the unveiling of a plaque affixed to its wall and to remember Caleb Cheeshahteaumuck, A.B. 1665, of the Wampanoag tribe of Martha's Vineyard, who was the first American Indian to graduate from Harvard College. The plaque commemorates Harvard's Indian College and its first scholars. Besides Cheeshahteaumuck, these included his classmate Joel Iacoomes, who perished in a shipwreck just before Commencement, two others who died of disease before completing their courses of study, and one who left to become a mariner.

"It's a memorable day when Harvard puts us back in its history," said Susan K. Power, tribal elder of the Standing Rock Sioux tribe and mother of Susan Power '83, J.D. '86, who would give a reading from her forthcoming book, Strong Heart Society, later in the day. The plaque had been the elder Power's idea.

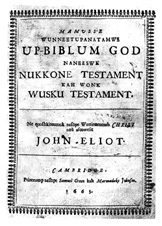

The "Indian Bible," 1663, a translation into Algonquian printed at the Indian College.PHOTOGRAPH COURTESY HARVARD COLLEGE LIBRARY The "Indian Bible," 1663, a translation into Algonquian printed at the Indian College.PHOTOGRAPH COURTESY HARVARD COLLEGE LIBRARY |

The speakers' platform at the ceremony was chock-a-block with Native Americans and senior Harvard administrators. The master of ceremonies was Dean Newton '92, J.D. '95, president of the alumni association of the Harvard University Native American Program. The mandate of that program, which was established in 1970 and expanded in 1990, is to advance "the well-being of indigenous peoples through self-determination, academic achievement, and community service."

One point of the ceremony, said President Neil L. Rudenstine, was "to remember and honor the fact that Native Americans had this land long before there was a Harvard." By its 1650 charter, he noted, the new college was charged with providing for the education of both English and Native American youth. Today Harvard offers two interdisciplinary courses on Native American nation-building and courses in Native American law and education. The first Bible published in North America, in the Algonquian language, was printed on the press housed in the Indian College, built in 1655 near the site of the new plaque.

The Indian College fell down in 1695, said Jeremy Knowles, dean of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences, and Harvard's early attempts to educate Native Americans tumbled also, owing in part to the insistence of the faculty that Indians be taught Latin and other matters valued by clerics. The relevance of the curriculum to the challenges and opportunities of their probable future lives did not seem, to the Indians, acute, said Knowles. He celebrated today's Native American Program, which "is enabling us to reclaim at last a role in the education of Native Americans and in Native American scholarship."

Beverly Wright, chairperson of the Wampanoag tribe of Gay Head, Massachusetts (townspeople voted later in May to change its name to its original Native American, Aquinnah, a reversion that must be approved by the state legislature), reported that more than 120 Native Americans from 40 tribes study at Harvard today, for which the University is to be commended, she said. (She seized the occasion to scold Massachusetts for denying the Wampanoags a license to build a gaming facility in Fall River. Education costs money, she noted.)

Cheeshahteaumuck's signature, from a surviving document.PHOTOGRAPH COURTESY HARVARD COLLEGE LIBRARY Cheeshahteaumuck's signature, from a surviving document.PHOTOGRAPH COURTESY HARVARD COLLEGE LIBRARY |

Next, Lorie Graham and Peter Golia of the Native American Program unveiled the handsome slate plaque while the Young Blood Singers drummed and sang an honor song. Behind the inscription on the plaque is a faint, incised representation, designed by Noelani Crawford, of a turtle, a powerful symbol in Indian creation stories. The plaque, which cost $12,000 and was carved by John Hegnauer, was the gift of Ray Halbritter, J.D. '90, to his parents, sister, and brother. He is leader of the Oneida Indian nation of New York.

Dean of the College Harry Lewis introduced Pablo Padilla '97, of the Zuni Pueblo and Mather House, who offered appealing, often humorous reflections on his undergraduate experience. The first of his tribe to attend Harvard, he comes from a family where English is rarely spoken and didn't learn the language until he was 10 or 11. Everyone he grew up with is poor. At Harvard, Padilla has not learned to aspire to be an investment banker. But, he said, old friends "tell me that now I walk too fast, talk too fast, and eat too fast." Back home, said Padilla, no one ever honks his car horn except to say hi to a friend in a passing car or on the street. When he was ready to begin his life at Harvard, his parents drove him across country. When they got to Harvard Square and were looking for a place to park, other motorists honked at them so insistently that they were quite astonished by the friendliness of the place.

A closing prayer was offered by Manley Begay, Ed.M. '89, director of the National Executive Education Program for Native American Leadership, which is based at the Kennedy School of Government. It was a long prayer, in Navajo, and even to some who did not understand the softly spoken words, it had a moving power.

Main Menu · Search · Current Issue · Contact · Archives · Centennial · Letters to the Editor · FAQs

![]()