Performance highlights for fiscal 2016:

•The endowment’s value stood at $35.7 billion as of June 30, the end of fiscal year 2016, a decrease of $1.9 billion (5.1 percent) from $37.6 billion a year earlier—a total that had finally exceeded the nominal peak value, not adjusted for inflation, reported in fiscal 2008, just before the financial crisis and ensuing recession. Updated, September 30, 2016, 10:45 a.m.: The University has announced the appointment of N.P. Narvekar, CEO of the Columbia University endowment-investment organization, as the new president and CEO of Harvard's endowment; read a complete report here.

•Harvard Management Company (HMC) recorded a negative 2.0 percent investment return on endowment assets during fiscal 2016, following positive returns of 5.8 percent in the prior year and 15.4 percent in fiscal 2014. (The return figures take investment fees and expenses into account.) Weak results, in a challenging investment environment for most endowments, were foreshadowed during the summer, as previously reported. The results modeled there assumed a modestly positive return on Harvard’s endowment investments; the results reported today—the (2.0) percent return—trail that estimate. Updated September 23, 2016, 11:40 a.m.: Yale reported a positive 3.4 percent investment return for fiscal 2016, enabling it to report an 8.1 percent cumulative annualized rate of return during the past decade. Given the positive investment return, the value of the Yale endowment decreased minimally, from $25.6 billion to $25.4 billion, after accounting for distributions, which appear to have exceeded $1 billion. Updated September 28, 2016, 11:00 A.M.: Stanford reported an investment return of negative 0.4 percent; after accounting for endowment distibutions ($1.13 billion) and gifts received, the endowment rose 0.8 percent in value, to $22.4 billion. Updated October 11, 9:05 a.m.: Princeton reported a positive investment return of 0.8 percent for the fiscal year, joining Yale as the only Ivy institutions to have positive returns for the period. Columbia reported a negative 0.9 percent investment return for the period—the last under the management of N.P. Narvekar, HMC's new leader.

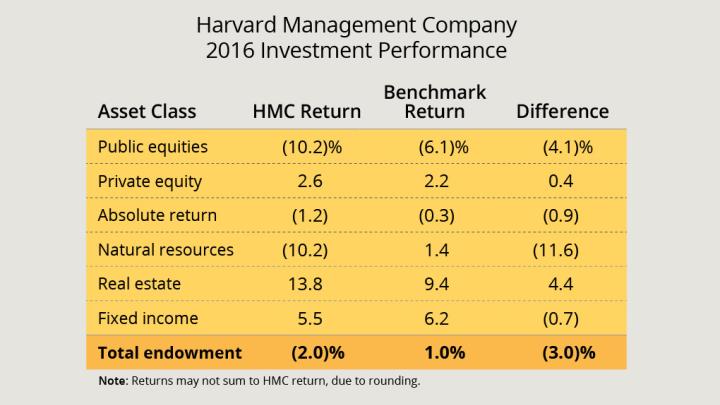

•HMC highlighted very strong returns for its real-estate investments, consistent with results in recent years and with other institutions’ fiscal 2016 results, but offsetting large losses in natural-resources and public-equities investments (see chart above and discussion below). Overall, HMC’s returns were 3 percentage points below its market benchmarks for its portfolio; had performance matched the benchmarks, the return for the year would have been slightly positive.

•The decline in endowment value reflects three intersecting factors:

- the negative investment return;

- the regular distribution of funds to support Harvard’s operations (reported as $1.7 billion—the largest source of revenue for the University budget), and possibly other one-time distributions, so-called “decapitalizations”; and

- the partially offsetting effect of gifts added to the endowment—the fruits of the capital campaign, which has now reported more than $7 billion of gifts and pledges. (Not all gifts are for endowment; many donors contribute funds for current use, or to underwrite building projects.)

(Exact figures for the operating distribution, decapitalizations, gifts, and pledges await publication of Harvard’s annual financial report later this autumn.)

•This year’s decline, after the long nominal recovery, comes as Harvard calculates that in inflation-adjusted terms, the fiscal 2015 endowment value “remains below the fiscal 2008 value, by approximately $5 billion.” That loss of purchasing power has now been exacerbated, a worrisome development because the endowment plays a crucial role in supporting the operations of a University budget $1 billion larger than in fiscal 2008. (see “Why It Matters,” below). In its extensive annual report issued last year, HMC identified its fundamental mission—assuring the financial underpinning for Harvard’s current and future academic strength—and as a result, its highest priority: achieving a long-term real return of 5 percent or more above inflation measured by the Higher Education Price Index, which is currently running at about a 2 percent annual rate.

•HMC also set a competitive goal of achieving top-quartile performance over an extended period relative to 10 peer university endowments—and noted that it had been in the bottom quartile for fiscal years 2011 through 2014. Relatively few peers have reported yet, but given HMC’s negative return, particularly relative to its market benchmarks, that record of underperformance may now be extended.

The results come at an unsettled time: after new president and CEO Stephen Blyth unveiled a sweeping overhaul of HMC’s asset allocation and relationships with external fund managers last year, it was announced during Commencement week that he would begin a medical leave immediately; chief operating officer Robert Ettl became interim CEO. In late July, Blyth’s resignation was disclosed, along with the hiring of a search firm to identify a new HMC leader.

This report examines HMC’s fiscal 2016 results; puts the endowment into the larger context of Harvard’s finances; and considers the challenges involved in improving performance.

The Year That Was

The Harvard Management Company (HMC), which invests the University’s endowment and other financial assets, today reported that the endowment’s value declined 5.1 percent, to $35.7 billion, as of the end of the fiscal year, this past June 30. That compares to a 3.3 percent gain in the endowment’s value during fiscal 2015.

This report was expected to be the first reflecting HMC’s new asset-allocation model, new relationships with external fund managers, and other changes put in place by Stephen Blyth, president and CEO, and described in his annual report last year. Instead, it comes in the wake of his unexpected leave and then departure after just 17 months in charge of the organization. Given the long-term nature of investments in illiquid asset classes that underlie value-added returns (such as private equity, venture capital, natural resources, and real estate), it was assumed that the changes Blyth outlined in a comprehensive effort to improve HMC’s portfolio would pay off only over a significant period of time. The risk is that continuing changes in HMC leadership, personnel (a new managing director for natural-resources investing was announced in mid August), and perhaps strategies may extend this transition, possibly deferring the hoped-for gains in performance.

In absolute terms, the endowment’s value declined $1.9 billion, trailing a back-of-the-envelope calculation prepared several weeks ago.

The decrease during the year just ended represents the interaction of three factors:

Depreciation. HMC’s in-house and external money managers suffered an aggregate 2.0 percent investment loss on endowment assets (after all expenses) during fiscal 2016. That produced a decline in value of perhaps $0.75 billion to $36.9 billion (disregarding other transfers and timing differences that go into the final rate-of-return calculation and reported endowment value). In recent years the rates of return were as follows, illustrating both the magnitude of changes in the value of the endowment (after large distributions to support the University operating budget, discussed immediately below) when investment returns are strong, and the volatility of those rates of return:

- Fiscal 2015: 5.8 percent (year-end value $37.6 billion)

- Fiscal 2014: 15.4 percent (year-end value $36.4 billion)

- Fiscal 2013: 11.3 percent (year-end value $32.7 billion)

- Fiscal 2012: (0.05) percent (year-end value $30.7 billion)

- Fiscal 2011: 21.4 percent (year-end value $32 billion)

- Fiscal 2010: 11.0 percent (year-end value $27.4 billion)

Distributions. The endowment’s value is reduced (in years of negative investment returns, further reduced) by distributions to support Harvard’s operating budget, and other distributions for one-time purposes (“decapitalizations”). The operating distributions totaled $1.59 billion in fiscal 2015, and were budgeted to increase perhaps 4 percent this past year. They in fact appear to have grown somewhat more, reflecting distributions on various transferred funds and new monies received, resulting in the $1.7 billion in fiscal 2016 distributions reported. Decapitalizations vary widely from year to year; the fiscal 2015 sum was $193 million. (Comparable figures for fiscal 2016 become available when the University’s annual financial report is published later this autumn.)

Gifts. Finally, the endowment’s value is augmented by capital gifts received and pledges of gifts for the endowment made during the year. The gift sum totaled $338 million in fiscal 2015 (and $513 million in fiscal 2014, more than double the fiscal 2013 figure)—reflecting the proceeds from the campaign. And there is a long runway, too: the annual financial report showed total pledges receivable of $2.25 billion at the end of fiscal 2015, up a robust 41 percent from $1.59 billion the prior year—pledges that gradually turn into gift proceeds, whether for near-term use, new buildings, or as endowment balances. (Pledges specifically for the endowment constituted $1.17 billion of that $2.25 billion as of June 30, 2015.) Again, the exact figure will be released with Harvard’s fiscal 2016 financial report this autumn.

Thus, the rough arithmetic would be: $37.6 billion beginning value minus $0.75 billion (fiscal 2016 investment losses), minus $1.7 billion (operating distributions for the University budget), plus perhaps $0.5 billion or more in gifts for endowment received and new pledges, equal the endowment’s $35.7-billion value as of this past June 30.

Why It Matters

HMC’s investment results are much more than fodder for an annual arm-chair guessing game. The resources provided by the endowment have become essential to Harvard’s academic mission; as the accompanying graph shows, endowment distributions have accounted for a steadily rising proportion of revenues.

Data from Harvard University Fact Book, Office of Institutional Research, Office of the Provost.

In fiscal 2015, endowment distributions provided 35 percent of operating revenues; the other sources of income were tuition and student fees (20 percent), sponsored-research support (18 percent), gifts for current use (10 percent, in a period of elevated philanthropy from the capital campaign); and all other (17 percent).

This represents a slightly greater reliance on endowment-derived revenues than in fiscal 2008, before the financial crisis. (The apparently greater reliance on endowment funding in the subsequent few fiscal years represents timing and budget effects as the University adjusted its spending, and incorporation of certain outsized decapitalizations.)

Expounding on the endowment’s significance in a report to the U.S. Congress this spring, President Drew Faust wrote that generations of philanthropy and investment exempt from taxation have produced the endowment, now “the University’s largest asset and our largest source of financial support.” Moreover, that role has grown:

Tuition alone does not cover the costs of educating a student, and research grants do not cover the full cost of the research enterprise. Increasingly, endowments play a significant role in bridging these gaps and making it possible for Harvard to pursue its mission. Reliance on endowment spending has grown substantially in recent years. Less than 20 years ago, one in five dollars spent was from the endowment; today, it is one in three.

And to underscore the point about libraries, laboratories, and professors, she noted, “A cost that is borne by the endowment is one that does not have to be paid with tuition dollars.”

Changes in the value of the endowment affect University and school operations gradually: to enable rational planning, based on “a predictable stream of available income,” as the annual financial report puts it, the “endowment distribution is based on presumptive guidance from a formula that is intended to provide budgetary stability by smoothing the impact of annual investment gains and losses” and making adjustments for “expectations about long-term returns and inflation rates.”

Presumably, the upward trajectory from the modest investment losses in fiscal 2012 toward double-digit positive returns in the succeeding two years led the Corporation to bump up the distribution. Now that trajectory has reversed, and the formula will take into account the decline from the 15.4 percent (2014) and 5.8 percent (2015) returns to the just-reported 2.0 percent investment loss—and corresponding 5.1 percent decline in the endowment’s value.

It is for the Corporation to determine exactly what adjustment to make, but the effects of restraining future endowment distributions will not be uniform.

For a $4.5-billion enterprise like Harvard (fiscal 2015 operating revenues), downshifting from annual increases in the endowment distribution of approximately $60 million in recent years (and apparently more in fiscal 2016), to potentially no increase in fiscal 2018, would obviously cause some discomfort. Annual changes in salaries, wages, and employee benefits alone—about half of Harvard’s expenses—have consumed much or all of the increased endowment distribution in recent years.

But for the certain schools, the prospective adjustment might be much more fraught. Based on fiscal 2015 data, these units were particularly endowment-dependent:

- the Radcliffe Institute, 89 percent of operating revenues;

- Harvard Divinity School, 70 percent; and

- the Faculty of Arts and Sciences (FAS), 51 percent.

Nor are other expenses level:

- FAS administrators, for example, point out that the renovated undergraduate Houses cost more to operate: their systems have been brought up to modern codes, common spaces are air-conditioned, unused basement storage areas have been repurposed into classrooms and studios, and new bed- and bathroom configurations result in greater reliance on professional janitorial services.

- The science and engineering complex in Allston will create vital research and teaching spaces—but it means operating a half-million square feet of new facilities.

In this sense, across the campus, campaign-funded benefactions entrain greater running costs, at least some of which faculties presumably hope to defray with rising endowment distributions. If lower distributions are forecast, belt-tightening may be expected to begin promptly. And from the perspective of their administrative deans, reducing expected endowment distributions means resetting their schools’ longer-term financial plans to a lower level; they cannot responsibly forecast future investment returns that will recover reduced revenue anytime soon.

At the same time, the adoption of Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) for financial reporting (one of Harvard’s many internal management reforms in the wake of the 2008-2009 crisis) will shine a brighter light on facilities depreciation; as the Corporation reviews school budgets, it can be expected to insist that they regularly fund building renewal—a major cost (like the $1-billion-plus House renewal) that deans have been able to defer, or avoid, in the past.

For units operating at a loss on a cash basis—of late, FAS, the School of Engineering and Applied Sciences, and Harvard Medical School—these discomforts may compound.

The Investment Context and Peers’ Performance

Following the favorable market conditions that supported strong returns in fiscal 2014, and then deteriorating conditions in fiscal 2015, the investing environment around the world was even less favorable during this past year.

For equity investors, global market indexes including United States equities registered losses of 3 percent to 4 percent in fiscal 2016: domestic returns were generally stronger, with the Standard & Poor’s 500 index of large-capitalization U.S. stocks appreciating about 4 percent; but international and especially emerging markets were down sharply. Private equity returns are difficult to measure, given the diverse nature of the assets and how they are valued, but appear to have been generally, if only modestly, positive.

The outstanding asset category in fiscal 2016 was the fixed-income sector, as unexpectedly low interest rates yielded returns of 6 percent to 7.7 percent on relatively conservative investments, as measured by U.S. aggregate and municipal-bond indexes. Real estate, reflecting characteristics of fixed-income and equity investments, was also strong. Commodities continued under sharp pressure—witness depressed oil and gas prices, and weak demand for many metals, reflecting subdued industrial growth throughout the world.

Because investors like HMC typically underweight relatively conventional fixed-income holdings, they tended not to capture the full strength of such investments this year. The Wilshire Trust Universe Comparison Service reported that the median return for large endowments was approximately negative 1 percent, given their significant commitment to alternative assets (private equity and venture capital; hedge funds—which appear to have performed poorly in fiscal 2016; natural resources and commodities; and real estate). In contrast, an indexed 60 percent stock/40 percent bond portfolio, which would have more U.S. equity exposure than most large endowments, and much more bond exposure, returned 4 percent for fiscal 2016.

It is early in the annual reporting season (most peers with large, diversified endowment portfolios, including Yale, Stanford, and Princeton, have yet to publish results Updated September 23, 2016, 11:40 a.m.: Yale has now reported; see a summary of its results at the top of this article), but the results to date are indicative of what kind of year investors had. Among higher-education institutions, the following reported these rates of returns during the fiscal year, and the resulting values of their endowments:

- MIT: 0.8 percent, down from a leading 13.2 percent in fiscal 2015. After taking spending into account, its endowment decreased 2.2 percent, to $13.2 billion from $13.5 billion.

- University of Virginia: negative 1.5 percent, compared with a positive return of 7.7 percent in fiscal 2015; $7.6 billion. The University of Virginia Investment Management Company, which has a very strong long-term record and excellent, detailed financial reporting, highlighted strong results in private real-estate and domestic buyout (a private-equity strategy) investments, but losses in public and growth equities, and natural resources.

- Bloomberg has reported uniformly negative results among public university endowments with $1 billion or more of assets, with the returns for 11 institutions ranging from negative 3.4 percent at the University of California system and Ohio State to negative 0.8 percent at Penn State.

The $300-billion California Public Employees’ Retirement System (CalPERS) differs in size and purpose from Harvard’s endowment, but its returns and comments on performance by asset class have often helped to illuminate the environment in which HMC operates. CalPERS reported preliminary fiscal 2016 returns of 0.61 percent. In the preceding fiscal years, it had reported returns of 2.4 percent (2015; Harvard 5.8 percent); 18.4 percent (2014; Harvard 15.4 percent); and 12.5 percent (2013; Harvard 11.3 percent). For fiscal 2016, CalPERS noted very strong returns on fixed-income investments (9.29 percent) and real-estate and infrastructure assets (7.06 percent and 8.98 percent)—but losses on public equities and forest land, and only nominally positive returns (1.70 percent) on private equities. (Real-estate and private-equities figures were based on March 31 valuations).

Harvard’s Performance

HMC’s (2.0) percent investment return—3.0 percentage points below its aggregate benchmark—had a sharply depressing effect on longer-term returns, as well. Its five-year cumulative annualized return is now 5.9 percent, and the 10-year return is 5.7 percent. All three rates of returns trail the 60/40 U.S. stock/bond portfolio (a proxy for relatively uncomplicated, and lightly managed, investment pools), for which the one-, five-, and 10-year returns are now, respectively, 5.0 percent, 8.9 percent, and 6.9 percent.

According to HMC’s report, from interim CEO Robert Ettl, public-equity investments made up 29.0 percent of the assets: 10.5 percent domestic, 7.0 percent foreign, and 11.5 percent emerging markets. (This allocation is slightly below the 33 percent modeled under the previous asset model, as described in HMC’s fiscal 2015 “policy portfolio.”) Returns for these assets were, respectively, (4.9) percent; (14.2) percent; and (12.0) percent—for an aggregate public-equities return of (10.2) percent, 4.1 percentage points worse than HMC’s benchmarks for this mix of investments. The report notes that HMC has “repositioned our public equity strategy to rely more heavily on external managers,” while citing underperformance in external domestic-stock managers and closely correlated, underperforming investments in several portfolios. Accordingly, in June, the internal equity team was downsized; the strategy for external equity managers has been changed; and the internal and external equity investment managers now report to new leadership internally.

Private-equity investments, a key category for endowments like Harvard’s, now make up 20 percent of HMC’s assets, a modest increase from the prior policy-portfolio allocation. Precise allocations are not provided, but HMC’s report indicates that the U.S. corporate finance segment returned 8.3 percent; international corporate finance investments returned 1.0 percent; and venture capital, long a stellar performer, yielded a loss: (1.5) percent. As a whole, private equity returned 2.6 percent, slightly above the benchmark.

Fixed-income investments made up 12.5 percent of the portfolio: domestic bonds, 9.0 percent, foreign bonds, 1.0 percent, inflation-linked bonds, 2.0 percent, and high-yield bonds, 0.5 percent. Returns for these assets were, respectively, 6.7 percent; 10.9 percent; 1.6 percent; and 2.1 percent—for an aggregate fixed-income return of 5.5 percent, lagging the 6.2 percent benchmark for this mix of investments. The fixed-income allocation increased from the 10 percent policy-portfolio allocation in fiscal 2015.

Absolute-return assets (hedge funds and other diversifying strategies)—14 percent of the total, down modestly from the fiscal 2015 model—yielded a loss: a (1.2) percent return, modestly weaker than the (0.30) benchmark loss.

The natural-resources portfolio—10 percent of assets, down 1 percentage point from the policy portfolio—was battered. It produced a large loss, with a return of (10.2) percent, and sharply underperformed the market benchmarks, which yielded a positive 1.4 percent return. HMC’s report cites illiquid markets for timber and agricultural lands, crop losses affecting one South American asset afflicted by drought, and political and economic conditions impairing the value of another asset there.

Real estate, now 14.5 percent of assets, vs. 12 percent in the 2015 policy portfolio, has been an area of consistent interest for HMC in recent years. Direct investments, launched starting in fiscal 2010, now make up more than half the portfolio and earned a return of 20.2 percent. The portfolio as a whole returned 13.8 percent—4.4 percentage points better than the benchmark.

Peering into 2017, Ettl outlines an “investment landscape…full of uncertainty. With a backdrop of slowing growth and rich valuations, endowment returns could be muted for some time to come.” He cites strong liquidity in the portfolio, and the benefits of steps taken in recent years to change the organization and reposition assets. Ettl concludes, “Investing with best-in-class managers, properly allocating assets, thoughtfully structuring our portfolio, and collaborating across asset classes will be critical to our success.”

Looking Under the Hood

In the long view, HMC’s investment returns on endowment assets have declined, and become more volatile (see graph). In their letter accompanying the University’s annual financial report, the treasurer and CFO have taken to warning about “certain vulnerabilities” exposed by the financial crisis, including, as they wrote in fiscal 2012, “endowment dependence and volatility.” As HMC’s then-CEO Stephen Blyth described matters in his 2015 report, real returns, above the Higher Education Price Index

have declined steadily over time. This can be attributed to a number of factors: (i) a steady and substantial decline in the risk-free real interest rate—for instance, the real yield of the ten-year TIPS (Treasury Inflation Protected Security) has declined from 4.3 percent in 2000 to 0.6 percent today; (ii) a reduction in risk premia across asset classes due to significant liquidity injections; and (iii) fewer opportunities for outperformance (or “alpha generation”) across markets.

All investors face the first condition: the long decline in interest rates, which have hovered at historic lows since the financial crisis. The second condition presumably affects institutions, like HMC, that have profited from their commitment to less liquid, higher-yielding investments (in private equity, natural resources, real estate, and so on), consistent with their long-term horizons. Over time, such investments have attracted increasing flows of funds as other investors perceive the opportunities and seek similar returns for their own portfolios, driving down potential returns for everyone. The third condition may reflect the combined influence of the preceding two, perhaps plus factors unique to the University and HMC.

Data from Harvard University Fact Book, Office of Institutional Research, Office of the Provost.

These factors lend themselves to different narratives about HMC’s evolving performance—and prospects. The following are caricatures, but they serve an illustrative purpose.

One narrative begins with HMC’s sustained, robust performance from 1990 to 2005, under Jack R. Meyer, M.B.A.’69—particularly the nearly 16 percent annualized return from 1995 to 2005 (a strong period for similar investing institutions, too, but an era when HMC was among the top performers). During his tenure, HMC managed much of its assets internally, in effect operating as a collection of in-house, University-owned hedge funds, producing stellar results by concentrating successfully on underexploited pockets of the investment universe. Beginning in 1998, several of the top-performing teams of HMC investors departed to form their own, private investment organizations (usually with an initial, large sum to invest on Harvard’s behalf)—a trend throughout the asset-management industry, as many portfolio managers set up their own shops (contributing to some of the competitive conditions Blyth outlined, cited above).

After Meyer and several senior colleagues followed suit in 2005, forming Convexity Capital, HMC was briefly led by Mohamed El-Erian, HMC president and CEO from 2006 to 2007. In the midst of the sustained high returns that followed the dot.com bust, during the period from 2003 through 2007 (12.5 percent to 23 percent annual gains), HMC aggressively invested funds with external managers. And then, disaster: in fiscal 2009, the return on endowment investments was negative 27.3 percent, and the endowment plunged by $11 billion. (The University’s assets overall decreased by $14 billion, weighted down further by losses on interest-rate swaps and liquidity problems associated with investing Harvard’s short-term funds alongside the endowment assets.) HMC also had $11 billion of commitments to fund external investments pending at the end of fiscal 2008: calls on its capital and future cash flow it was in no position to fulfill.

Thus, Jane L. Mendillo, HMC president and CEO from mid 2008 (just before the financial crash) through the end of 2014, understandably had to focus, initially at least, on damage-control: enhancing liquidity; unwinding those burdensome investment commitments; strengthening risk management; and doing everything possible to maximize the asset managers’ flexibility while ensuring that the University budget was still supported, even at a somewhat reduced level during a period of austerity. As a result, HMC had less capacity to pursue attractive opportunities from 2008 through 2010, when the financial crisis and recession depressed asset prices, and therefore paid a penalty in terms of forgone returns during the subsequent, protracted period of recovery in the financial markets. Following Mendillo’s departure, Blyth set about to reinvigorate HMC’s culture, rethink asset allocation in the prevailing economic and investment environments, and repair and refine relationships with the strongest external asset managers—relationships he admitted had frayed—all in pursuit of stronger returns (see his views in an extended interview late last year).

An alternate narrative focuses less on external conditions than on changes in HMC’s hybrid investment structure (some portfolios managed internally, other funds contracted out to private investment partnerships), and its evolution over time. Thus, whatever the market and competitive circumstances for superior investments, this interpretation emphasizes HMC’s evolving pursuit of opportunities.

A decade ago, the annual report on compensation for HMC’s highest-paid personnel regularly prompted external commentary—and frequently, sharp criticism. That pay peaked in fiscal 2002 and 2003, when extraordinary returns earned in the foreign and domestic fixed-income portfolios (a hard-to-fathom 52.4 percent in the former and 31.1 percent in the latter for fiscal 2003, huge margins of outperformance relative to their respective market benchmarks) resulted in $35.1-million and $34.1-million paychecks for portfolio managers Maurice Samuels and David R. Mittleman. (They and Jeffrey B. Larson, a foreign- and emerging-markets-equities investor, who earned $17.3 million that year, realized high returns for HMC, and correspondingly high compensation, for several years.)

What strikes some observers today is not the debate over the size of HMC’s performance-based compensation packages (which have since been adjusted downward), but rather who received them. A decade ago, the portfolio managers who made the investment decisions consistently earned more than CEO Jack Meyer—in some of their peak years, by tens of millions of dollars, even as Meyer typically earned several million dollars annually. Thus HMC’s highest compensation went to the investment professionals whose fund commitments and trades yielded returns substantially better than the market results in their asset classes, and who were able to sustain those value-added results over time.

Scroll forward to this decade, and the results look different. With HMC now investing perhaps just 40 percent of its funds internally (and with the compensation formula revised to dampen the prior peaks), its top tier of compensation has shifted. The leading earners are the president and CEO, and the sector heads (public markets, alternative assets, natural resources), who presumably oversee internal portfolio managers and external investment-management firms, review strategy, and so on (review the most recent compensation reports, now released with a lag, for calendar years 2011, 2012, 2013, and 2014, respectively).

In other words, of late, HMC’s best-compensated personnel have typically come from the organization’s senior management ranks, rather than principally from HMC staff members directly responsible for investing assets and running portfolios. And when the latter have still ranked among HMC’s best-compensated staff members, they have typically earned in the range of $4 million to $9 million: far less than portfolio managers made at HMC in the prior decade—and a mere fraction of what some of them reportedly took home once they left HMC’s employ and set up their own private investment partnerships.

Theories of Change

HMC's underperformance relative to the endowments of peer institutions, with whom Harvard competes for talent, and relative to its long-term real-return goal, is costly. Through fiscal 2015, HMC reported last year, its 10-year cumulative annualized return was 7.6 percent, vs. 10.1 percent for Princeton, 8.7 percent for Stanford (which reportedly has undertaken a sweeping overhaul since mid 2015), and 10.0 percent for Yale. Applied to the $37.6-billion value then, the difference between HMC’s rate of return and Yale’s represents the loss of $900 million in investment earnings in a single year—an amount that compounds over time (if the gap is not overcome through subsequent outperformance). Assuming normal endowment distributions, gradually effected via the smoothing formula, that translates into $40 million to $45 million in lost revenue annually for University and school operations—again, a sum that compounds.

As reported in the fiscal 2016 results, of course, the endowment declined $1.9 billion in value, during a period of robust capital-campaign fundraising and the resulting flow of gifts for the endowment. If not recaptured by subsequent outperformance, over time that loss of value translates through the smoothing formula into annual operating income of $85 million to $95 million forgone. Relative to HMC’s long-term goal of real returns 5 percentage points above the increase in higher-education costs, the gap is about $4.5 billion in current investment value: if sustained, about $200 million to $225 million in annual, distributable income to support the academic budget.

“This has been a challenging year for endowments and clearly these are disappointing results,” the chair of HMC’s board of directors, Paul Finnegan, who is also Harvard’s treasurer, said in the University news announcement accompanying the results. Refering to the board and HMC’s executives, he continued, “[W]e are all focused on taking the steps necessary to ensure HMC can continue to most effectively support the mission of Harvard University over the long term.”

In the HMC report, Robert Ettl pointed to steps to “strengthen HMC as a organization,” during a period when “we recognize that execution was…a key factor in this year’s disappointing results”—on both an absolute and a relative basis. He also bluntly acknowledged, “The last 10 years, inclusive of the global financial crisis, have been challenging for the Harvard endowment.”

How, then, does HMC proceed?

According to the first narrative sketched above, the challenge before HMC’s board of directors is to identify a new president and CEO who can carry on the work begun by Stephen Blyth in early 2015:

- fine-tuning the organization and focusing its people on finding outstanding investment opportunities, consistent with the liquidity and risk disciplines instilled in recent years;

- implementing its new asset-allocation strategies; and

- building stronger relationships with demonstrably superior external asset managers, after a period when those relationships admittedly weakened.

In combination, pursuing those priorities should over time translate into stronger, and ultimately top-tier, returns on Harvard’s endowment assets.

At a minimum, achieving those goals in this way will require superb execution. With Blyth’s departure, two of the three authors of HMC’s complex new asset-allocation model have now left the organization. To the extent that external money managers want to know the CEO, the effort Blyth put into meeting them in New York, California, and overseas may have to be duplicated by his successor. And other relationships, within HMC and beyond, may have to be refreshed given other changes in its personnel during the past couple of years.

As one would expect, as a recently appointed interim leader, Ettl has been steering HMC in the directions laid out when Blyth was president and CEO. The fiscal 2016 HMC report refers to the asset-allocation model put in place last year, and its tactical application. Ettl addresses changes from internal to external management of the domestic-stock portfolios, following disappointing performance, and efforts to better structure and oversee those externally managed portfolios. He refers to steps toward more concentrated private-equity relatonships, to the expertise of the new natural-resources head, and the forthcoming appointment of a new head of absolute-return and public-market assets. And expanding on one of the priorities Blyth established, HMC has changed compensation for its investment professionals to better align their merit pay, if any is earned, with the overall institutional goals (for real returns above inflation, outperformance relative to market benchmarks, and outperformance relative to peer universities).

On the other hand, should the board and new leader decide that reshaping HMC reflects the second narrative—the eclipse, for whatever reason, of the internal portfolio managers, and the organization’s competitive challenge in securing and retaining the best talent for its investing staff—changes of a different kind might be required. One issue is scale. As reported, peer institutions that rely entirely on external investment managers select and oversee those relationships with relatively small in-house cohorts; Princeton’s PRINCO unit, for example has 42 full-time-equivalent employees, compared to the 175 to 250 or so employees at HMC at various times during the past decade. A transition to a new-model HMC, focused heavily, or exclusively, on external managers who have strong performance records implies very significant staffing changes—and compounds the challenge of securing still more of those superior external relationships.

Stephen Blyth deliberately deemphasized describing HMC as a hybrid organization (and the presumed expense savings that accrued as a result), as part of his effort to focus on maximizing investment performance as the paramount objective. His successor will likely pursue a path between tweaking HMC in its present form to refine performance, and upending it completely—the poles caricatured above. With a search for that successor under way, understandably, Paul Finnegan was not available to comment on criteria for candidates or on HMC board priorities for the person chosen to be president and CEO.

Whatever course the new leadership and HMC board set, it is imperative that they succeed. Since the financial crisis, Harvard has made extensive, essential changes in financial management and control:

- reforming the Corporation at least in part to deepen its financial expertise and oversight;

- adopting consolidated annual budgets and variance reviews;

- creating a University capital planning and budgeting process;

- fostering conversation among HMC, the central administration, and operating units to assure that the institution maintains sufficient liquid funds to meet its needs; and

- as noted above, adopting formal procedures to smooth endowment distributions, and moving toward GAAP accounting, in part to highlight the need for continuous maintenance of the University’s extensive, expensive physical assets.

Even with those disciplines and capacities in place, however, the very size of the endowment exposes Harvard to continued risk—from the markets, and from its fund managers’ execution.

In 2008-2009, the deep losses on endowment investments were compounded by the University’s handling of its short-term funds and its interest-rate swaps: multiple decisions that penalized future investment performance and produced a liquidity crisis, forcing Harvard to borrow heavily. (The recent announcement that Harvard seeks to refinance some portion of $2 billion of expensive tax-exempt debt issued from 2008 to 2011—see “Other Financial Developments” here—is a welcome sign that the University in a position to take advantage of current, lower interest rates, potentially saving many millions of dollars in coming decades. If effected, the refinancing will, if not fully closing another chapter in the financial-crisis era, at least reduce the carrying cost significantly.)

In fiscal 2015 and 2016, continued weak performance has reduced the value of Harvard's investments and penalized its future finances. Put bluntly, in an era of constrained public support for sponsored research and higher financial-aid costs (which lessen net tuition receipts), the University has become significantly more dependent on endowment distributions and philanthropy—the theme the president, treasurer, and CFO have been sounding. Given what was a $37-billion endowment, as the latest report indicates, the leverage is enormous:

- In a favorable year with 10 percent investment returns, Harvard can fund the entire operating distribution and retain an equal sum to support its future academic programs.

- In a year like fiscal 2016, when the endowment assets depreciate modestly, underperforming market benchmarks, and the University makes normal distributions for the operating budget, the decline in value essentially offsets the gifts for the endowment received during the course of the capital campaign to date ($1.5 billion from fiscal years 2011 through 2015, plus the fiscal 2016 sum to be reported): the proceeds realized from six years of concerted private and public fundraising.

Consistent investment results of course help attract prospective donors, so endowment performance and philanthropy—the twin pillars of the University’s finances—are linked. The treasurer and CFO will have a lot to talk about in their letter when Harvard's annual financial report is released.

But clearly, getting HMC on the right course is among the institution’s highest financial priorities.

Read the HMC report here. Read the news release here.