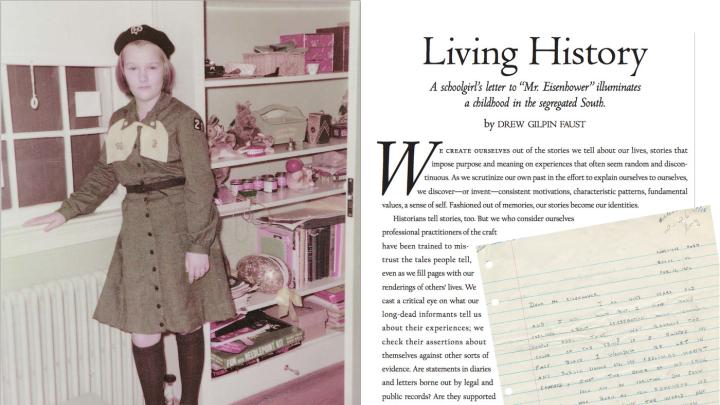

About perhaps no other public issue does President Drew Faust feel more passionately—nor express herself more personally—than America’s history and continuing legacy of racial division. In the spring of 2003, when she was dean of the Radcliffe Institute, Harvard Magazine published “Living History,” her essay about her girlhood in segregated Virginia in the wake of Brown v. Board of Education, in light of her subsequent career as an historian of the American South and the Civil War.

In early February, she was asked during a Faculty of Arts and Sciences meeting about her decision to speak out about highly publicized events in which unarmed black citizens had been shot by policemen. Faust responded by saying that having grown up in an era of segregation, and having marched during the Selma campaign for voting rights, the issues of rights for the disenfranchised and those discriminated against had always been central to her. The sense of injustice so evident in those earlier times was still felt by so many Americans, she continued, and that explained her decision to speak out.

This morning, in Memorial Church, Faust spoke directly about Selma, before departing for Alabama to join the fiftieth-anniversary commemoration of the Selma march. (President Barack Obama and his family are scheduled to participate.) The Reverend Jonathan Lee Walton, Pusey minister in the Memorial Church and Plummer professor of Christian morals, observed in an e-mail that when he learned about Faust's experience in Selma, and

[w]ith student activism on campus at a fevered pitch during the fall term, I could not help but think of the connection. The generational gulf that many students feel between themselves and those in prominent positions such as President Faust is often exaggerated. Thus, I thought Morning Prayers would be a wonderful moment for President Faust to simply bear witness to her own experiences as a student protester. And with the fiftieth anniversary of Bloody Sunday coming up on the calendar, I could not think of a more appropriate Morning Prayers speaker for March 6, 2015 on our campus. President Faust, and so many others, prove a simple yet profound point. Leadership does not begin with a position or title. It begins when one answers a call to get involved. No matter where you fall on the political spectrum, this is an important life lesson.

Throughout Lent, Memorial Church will hold events focused on Selma and civil rights; in his prayer after Faust spoke, Walton called on those present to both remember the past and to be "catalyzed to action" against injustice in the present.

Faust began her remarks by invoking Seamus Heaney’s vivid lines on history-changing moments. This is her address:

History

says, Don’t hope

On this side of the grave.

But then, once in a lifetime

The longed-for tidal wave

Of justice can rise up,

And hope and history rhyme.

“History says, Don’t hope,” the poet Seamus Heaney tells us. But sometimes, perhaps “once in a lifetime/The longed-for tidal wave/Of justice can rise up,/And hope and history rhyme.”

I was blessed, early in my life, to witness such a tidal wave, to see the injustices of the segregated Virginia society in which I grew up weakened by Brown v. Board in 1954, then challenged head-on by the Civil Rights movement that gained momentum in the years that followed. The issues seemed to me unambiguous; the compelling nature of what was right appeared both unquestionable and unavoidable.

Justice is born not only of hope. Justice makes demands beyond the patience and passivity Heaney portrays in his moving lines. When I leave this church today, I will travel to Alabama to join the commemoration of the fiftieth anniversary of the voting rights march at Selma. I was there 50 years ago, as a 17-year-old college freshman who skipped her midterms—which did not help my GPA—because I felt I had no choice. I had watched a flickering black and white TV as John Lewis and hundreds of others were clubbed and gassed on Selma’s Edmund Pettus Bridge as they sought their constitutional rights. I heard Martin Luther King declare that “No American is without responsibility.” And I felt the burden of that responsibility from the time I was small—growing up with the privileges of whiteness in the racial hierarchy of 1950s Virginia. So when King urged Americans to affirm that obligation by joining a renewed march, I knew I had to go. It was a moral imperative. I could do more than hope; I could act; I did not have to await a tidal wave; I could be part of it.

I'm not sure there has ever been a moment of such absolute and powerful moral clarity in my life since. Perhaps it's a function of aging—everything comes to seem more complicated, more amenable to compromise. As we used to say in those days: never trust anyone over 30. Or maybe we've learned in the aftermath of those heady triumphs—the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the Voting Rights Act of 1965—how justice requires perennial struggle. No victory is absolute; we have to keep our eyes on the prize to hold on—even to the Voting Rights Act itself, which is being threatened and eroded at the same time we are celebrating its passage.

But I will never forget that I was given a moment where I could help make history and hope rhyme. And I go to Alabama to remember as well those for whom it was far more than just a moment, or a series of abandoned midterms. I go in honor of Martin Luther King, of Hosea Williams, of James Bevel, of Diane Nash, of Andrew Young, of Jimmie Lee Jackson, of John Lewis, and so many others who have devoted their lives to the cause of justice and freedom.

As the movie Selma was being filmed, veteran Civil Rights leader Andrew Young was explaining to the actors who would be playing these heroic figures how they might understand what motivated their characters. “You must ask,” Young explained, “What are you willing to die for?” and then, “Live for that.”

I go to Selma to honor these lives—and all lives and times of such meaning and purpose.