We create ourselves out of the stories we tell about our lives, stories that impose purpose and meaning on experiences that often seem random and discontinuous. As we scrutinize our own past in the effort to explain ourselves to ourselves, we discover — or invent — consistent motivations, characteristic patterns, fundamental values, a sense of self. Fashioned out of memories, our stories become our identities.

|

| Catharine Drew Gilpin, Girl Scout, on February 9, 1957, the week she wrote to "Mr. Eisenhower." Not yet an historian, she misdated her letter, writing 1956. |

| Photograph courtesy of Drew Gilpin Faust |

Historians tell stories, too. But we who consider ourselves professional practitioners of the craft have been trained to mistrust the tales people tell, even as we fill pages with our renderings of others' lives. We cast a critical eye on what our long-dead informants tell us about their experiences; we check their assertions about themselves against other sorts of evidence. Are statements in diaries and letters borne out by legal and public records? Are they supported by the writings of contemporaries with different perspectives and agendas? We challenge the narratives of our historical colleagues as we endeavor to find the truth, and we build careers by revising interpretations, by piecing together data in new ways that yield a new plot, a fresh account, a richer understanding about a segment of the past.

To be a historian is thus to be in some sense a living contradiction. We are at once the agents and the objects of history. We are on the one hand individuals — like all others — struggling to fashion a coherent and stable narrative of our own lives that will provide the foundation of a self. Yet we are by education and inclination compelled to be skeptical of such stories. We must, paradoxically, place ourselves both outside and inside of history.

Arnold Toynbee wrote about this complex relationship with the past when he remembered witnessing Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee procession as a small boy. History, he felt then, was "something that happens to other people." Triumphant imperial Britain seemed in 1897 above history. But, he continued tellingly, if he had been a small boy in the American South instead of in London, he would have known that "history had happened to my people in my part of the world." He would have been inside it.

Letter courtesy of the Eisenhower Library

I knew from the time I was a small child in Virginia that I lived in history. When I was born, a half century after the Diamond Jubilee, the South was still breathing the air of war and defeat. The Lee-Jackson Highway took me to school; ubiquitous Confederate-gray historical markers memorialized battles like Cedar Creek, Belle Grove, or Bethel, or skirmishes along the Opequon and the Shenandoah; seven small marble slabs noted the presence of unnamed Confederate dead just behind my grandfather's grave in the Old Chapel cemetery; and my grandmother sought to inspire and instruct us with choruses of "I'm a good old rebel/That's just what I am/For this fair land of freedom/I do not give a damn" — impressing us in no small part by the entirely uncharacteristic use of profanity to underscore her passion. But my sense of history was more immediate as well. By mid century, the Civil War's unresolved legacies of race had assumed new urgency as the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court decision challenged the customs of racial segregation that had been legally enshrined by Plessy v. Ferguson in 1896. Now integration was to become the law of the land; schools, and then all of southern society, were to be transformed with "all deliberate speed."

I have always known that I became a southern historian because I grew up in that particular time and place. My sense of self, my story about how I became who I am, has always been situated in events now nearly a half-century old and the subject of academic study for many of my fellow historians. I developed a narrative about my childhood, about my identity as rebellious daughter, that I offered to all those who asked — and to some who didn't — a narrative that explained my redemption as a white southerner and my resurrection as civil-rights advocate and activist. In the preface to Mothers of Invention, published in 1996, I committed to print the story I had repeated so often.

My professional historical interest in the South grew out of those early years...for I lived in Harry Byrd's home county during the era of Brown v. Topeka and "massive resistance" to school desegregation....It was not until I heard news about the Brown decision on the radio that I even noticed that my elementary school was all white and recognized that this was not an accident. But I quickly penned a letter to President Eisenhower to say how illogical I thought this seemed in the face of precepts of equality I had already imbibed by second grade. I confronted the paradox of being both a southerner and an American at an early age.

Seeing this explanation in print was jarring, for it juxtaposed my own narrative with the stories that filled the rest of that book — stories I had subjected to the historian's critical eye, had researched and footnoted. Not a few of those footnotes cited letters written by women of all ages to their president — to Jefferson Davis, in this study of Confederate women. But if these letters, not to mention those written to Lincoln, to FDR, and to every other American president had been saved and archived, why not my letter to Eisenhower? It had never occurred to me. But I could no longer simply stand outside the past and make my judgments about it. I had to look at my own memories. I had to make myself the object as well as the agent of history. I had to find the footnote to document my own life.

It seemed a long shot. Perhaps the letter had been lost or misfiled. Perhaps it had never existed. Perhaps I had just thought about writing it or perhaps I had entirely invented a legendary past in order to root my rebellious teenaged years of the 1960s in a dramatic childhood epiphany and a personal myth of origin. Perhaps I had indeed written to Eisenhower, but not with the enlightened integrationist and egalitarian document of my memory. Perhaps I had sent something more consistent with the conventional segregationist views of the white society in which I lived. Perhaps the letter would be horrifying.

The papers of the Eisenhower administration are not stored, like those of the nineteenth-century presidents with which I was familiar, in the National Archives in Washington. Instead, they have been collected in the Eisenhower Library in Abilene, Kansas. And there, among 23 million pages of manuscripts, was my letter. "I have located a letter, " wrote archivist Herbert Pankratz in an e-mail titled "Letter by a School Child," "...in the White House Central Files. In the letter Miss Gilpin expresses her feelings about how Black Americans are treated and urges the president to make schools more open to minorities." But the letter was written in 1957, not 1954. Mr. Pankratz offered to mail me a copy.

As I waited for the envelope from Abilene, I continued to wonder and worry about what I had written. Why 1957? Clearly I wasn't responding to Brown. Yet one thing I did know. In 1957 I would never have written about "Black Americans." That must have been a description of my letter composed much later by an archivist who was creating a calendar of materials in the Central Files. "Black" was a usage introduced in the mid to late 1960s; I had probably, I thought ruefully, written about "colored people."

"Dear Mr. Eisenhower," the letter began. "I am nine years old and I am white, but I have many feelings about segregation." I greeted the letter with some relief, with surprise — and at the same time with the eye of the historian who has subjected thousands of such documents to critical scrutiny. I have taught classes that have spent hours discussing a single text like this one — providing context, analyzing word choice, sentence structure, shape of argument, looking for what it has to reveal about another place and time. I have been deeply moved by discovering in a collection of family papers a bloodstained communication from a soldier announcing his own impending death. I have been excited to recognize that the slave names in a white owner's account book represent not just his record of profit and loss but tell a subversive story of black family ties maintained in face of slavery's oppressions. I have always felt that documents somehow magically connected me to the past; reading manuscripts has always been my favorite part of being a historian — even though I have always been slightly ashamed to enjoy such antiquarianism and sentimentality — both highly suspect in the eyes of professional historians. Now here was a copy of a letter I had written, a letter about which I had only vague and inaccurate memories, a letter that not only represented some earlier version of whoever I am, but was available to any historical researcher as part of the Dwight D. Eisenhower Library of the National Archives of the United States. This was no longer just my letter; it had officially become archival; it was now what historians respectfully call a Primary Source.

The letter is written on lined, three-hole, notebook paper, which I must have taken out of my school binder. This seems consistent with my memory that I never told my parents I was writing to the president. They discovered what I had been up to only when a formulaic acknowledgement arrived from the White House. They were stunned — both that I should have written to the president and that I should have expressed the thoughts that I did. I printed in block letters, perhaps worried that my handwriting would otherwise be illegible. I wrote the letter, fittingly — though I doubt I knew this — on Lincoln's Birthday in 1957. I was, as the first line of the letter proclaimed, nine years old. I also wanted the president to know — in my first sentence — that even if I was very young, even if I was not among those feeling the force of discrimination, I felt strongly about segregation.

I grew up in a privileged family in the rural Shenandoah Valley. Much of the western part of the state of Virginia had a very small black population, but my county, Clarke, had been home to younger sons of Tidewater gentry families during the eighteenth and early nineteenth century, and these Burwells, Byrds, Randolphs, and Carters had brought their slaves with them to the Valley. The descendants of the white owners and the black laborers remained, joined by newer families like mine, which had come to the Valley at the turn of the twentieth century. In 1950, Clarke County's population of 7,074 was 17 percent black; in adjacent Warren and Frederick Counties, the percentages were 8 and 2 percent; in Loudoun and Fauquier, slightly to the east, the percentages were 19 and 26. This was not the Deep South, and I remember no signs designating water fountains or waiting rooms as Colored or White. But it was a community of rigid racial segregation nonetheless, with lines drawn by custom and common understanding. There were separate black and white schools; such restaurants and other public facilities as existed in the largely rural county were restricted to whites. In our own house, the black cook and handyman had a separate bathroom. When I once used it, my mother reprimanded me for invading their privacy.

In February 1957, I was in the fifth grade of an all-white school in Millwood, population approximately 200, the nearest settlement to our farm and the site as well of the all-white Episcopal church to which my family belonged. The county seat, Berryville, eight miles away, had fewer than 1,000 inhabitants; Washington, D.C., was 60 miles to the east. I am not sure where we got our news. We had no television, but I remember the almost constant chatter of the radio — especially in the car as I was driven to school or church or piano lessons. The Washington Post was the nearest major newspaper. Somehow I managed to feel engaged with what was happening in the world. I worried in 1956 about refugees from the Hungarian Revolution and wrote about them in school; I would worry in 1957 that the launch of Sputnik meant the Russians might try to take over America. Cold War anxieties had made their way to rural Virginia. And I worried about what was happening in the South.

In the winter of 1956-7, the news was filled with stories about the growing conflict over civil rights. The preceding fall the Post had reported regularly on the progress of the Montgomery bus boycott and the rising prominence of Martin Luther King. In Washington itself, battle was being joined over what ultimately became the 1957 Civil Rights Act, the first significant piece of civil-rights legislation since Reconstruction. But in February, Congress was still in the midst of hearings and confronted threats of a Senate filibuster from the South. Alabama state judge George Wallace testified on February 6 that the bill would make federal judges "dictators" and undermine precious rights of the states; the attorney general of Georgia claimed that in creating a civil-rights division charged with protecting civil and voting rights, the bill would transform the U.S. Department of Justice into a "Soviet-type gestapo." Yet while the Post editorialized in favor of guarantees of rights for black Americans, even its own advertising pages testified to rather different assumptions. Help Wanted notices specified "Colored Men" or "Men. Over 18 (White)." And housing ads announced "Sale DC Houses. Colored-Upper NW. True Splendor" or "Colored-Bargain. Modern 2 Family Brick. Only $395 Down."

|

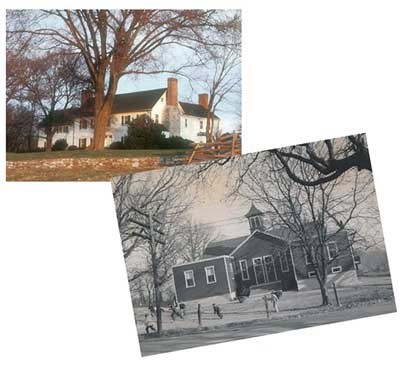

| Lakeville Farm, in western Virginia, the author's childhood home. A 1956 view of the all-white school she attended in nearby Millwood. |

| Photographs courtesy of Drew Gilpin Faust |

When Eisenhower traveled to Georgia in early February 1957 for a weekend visit to the plantation of his Secretary of the Treasury, the local Presbyterian minister greeted him with a Sunday-morning sermon describing "racial tensions that hang over our southland like a heavy thunderbolt." These tensions were nowhere heavier in early 1957 than in Virginia.

Virginia was not an obvious leader for southern opposition to the Supreme Court's rulings on desegregation. In many ways the state had become increasingly oriented toward the North; its population was less than one-quarter black, and political scientist V.O. Key had in 1949 proclaimed the state's race relations as "perhaps the most harmonious in the South." Integration of higher education was already quietly underway with the admission of a few black students to the University of Virginia and Virginia Polytechnic Institute. State officials, including Governor Thomas Stanley, initially responded to the announcement of the Brown decision with calls for compliance. Stanley promised to "work toward a plan...in keeping with the edict of the Court."

But the most powerful man in Virginia politics — U.S. Senator, former governor, and Clarke County resident Harry Byrd — took a different perspective. The Court decision, he proclaimed, posed "the greatest crisis since the War Between the States." The actions of the Court threatened so to extend federal power as to establish "totalitarian government." Byrd's militant and unyielding opposition and the political effectiveness within the Commonwealth of the fabled — indeed notorious — Byrd Machine would derail efforts by moderates to design a workable plan of compliance and place Virginia at the head of the South's battle against Brown.

|

| Raphael Johnson and Victoria Wilson, the handyman and cook for the Gilpin household, also figured in Drew Gilpin's dawning awareness of the unspoken rules of racial interaction. |

| Photographs courtesy of Drew Gilpin Faust |

Harry Byrd had entered politics just after the turn of the century and had controlled a powerful statewide Democratic machine for four decades. After serving as governor, he joined the U.S. Senate in 1933 and quickly became a national figure, a leading opponent of FDR and the New Deal, and the embodiment of the growing alienation of southern Democrats from the growing liberalism of the national party.

Byrd had long claimed the role of champion of the Constitution against the expansion of federal power and, in the tradition of his states' right forebears who had defended the prerogatives of the South in the decades before the Civil War, he embraced two doctrines to serve as the foundation for what would prove a last-ditch battle against integration after Brown. "Interposition" and "massive resistance" became the watchwords of the Byrd movement and of the growing struggle against desegregation across the South. Invoking John C. Calhoun's early-nineteenth-century language of nullification, the first doctrine argued that the contractual provisions of the U.S. Constitution provided for the interposition of state sovereignty between the dictates of federal courts and the actions of local school boards; the second doctrine, of "massive resistance," became a rallying cry for states to use this power to block the implementation of Brown.

In early February 1956, the Virginia legislature adopted an interposition resolution and urged "our sister States" to join in "prompt and deliberate efforts to check this and further encroachment by the Supreme Court, through judicial legislation, upon the reserved powers of the States." In the course of the next year, seven more states followed, passing their own interposition measures. Under pressure from Byrd and his allies, Virginia's Governor Stanley abandoned his earlier moderation and convened a special session of the General Assembly in August 1956 to consider a program of massive resistance. With Byrd forces in control, the legislature adopted 23 segregationist laws, including five measures explicitly designed to intimidate the NAACP. At the core of the program of massive resistance was a law that removed control over any school integrated by court order from its local authorities to the Commonwealth of Virginia. The governor would then close the school, thus enshrining state power over either federal or local prerogatives. This policy assumed that no public education at all was preferable to desegregated schools. In September 1958, the threat of massive resistance became reality when the governor shut down Warren County High School in Front Royal, just 18 miles southwest of Millwood, rather than permit 22 black pupils to enroll under federal court order. As the state pursued its intransigent course, high schools in Charlottesville and Norfolk were closed as well, denying public education to more than 13,000 of its black and white citizens. But in January 1959 both the Virginia Supreme Court of Appeals and the federal district court in Norfolk declared the state's school-closing measures unconstitutional. Within days, Virginia's governor broke his long and deep ties with the Byrd Machine and appeared before the General Assembly to call for an end to massive resistance.

When I had written to President Eisenhower nearly two years earlier, I did not know how the battle over Virginia's schools would turn out. Nor, of course, did I anticipate the struggles that would follow across the South as Eisenhower sent troops to uphold federal authority in Little Rock the next fall, or as the civil-rights movement extended well beyond school issues and spread to Greensboro, Albany, Orangeburg, Birmingham, Selma, and Mississippi. So what was it that prompted me on a February day in 1957 to appeal to the president? What I remember is that I heard something on the radio as I was being driven home from school by Raphael Johnson — a black man who worked for my family, doing everything from mowing the lawn, shining shoes, and washing floors and windows, to transporting my brothers and me around the county, entertaining us all the while with quizzes on state and world capitals or the order of the presidents. I was in the car with Raphael when I heard something that made me realize that black children did not go to my school because they were not allowed to, because I was white and they were not.

I may well have heard a story about that day's decision by Norfolk federal judge Walter Hoffman to set August 15 as the deadline for integration in the Tidewater city of Newport News. Or I may have heard reports of Virginia's appeal the preceding day to delay federal desegregation mandates for Arlington and Charlottesville. But why did I respond to these reports, rather than news the preceding fall of Montgomery bombings? Or of the massive resistance legislation passed in Richmond in August and September?

In my memory, in the story I had often told of that trip home from school, I asked Raphael if what I had just understood was true, whether I would be excluded from my school if I painted my face black. I came home and wrote these very words in my letter, not now as a question but already transformed into a declaration of outrage to the president. "If I painted my face black I wouldn't be let in any public schools etc. My feelings haven't changed, just the color of my skin."

What I remember is that Raphael did not answer my question. My probings about the unarticulated rules of racial interaction made him acutely uncomfortable; he was evasive. But his evasion was for me answer enough. How was it possible that I never asked that question or saw those realities until I was nine years old? How could I have not noticed before? Why did I notice then? And given my long obliviousness, why did these discoveries make me so upset? How did I know how to read Raphael's response and not to press him? Why did I have, as I wrote Eisenhower, "many feelings about segregation?"

It was not because race was a subject much discussed in my household. I lived in a world where social arrangements were taken for granted and assumed to be timeless. A child's obligation was to learn these usages, not to question them. The complexities of racial deportment were of a piece with learning manners and etiquette more generally. There were formalized ways of organizing almost every aspect of human relationships and interactions — how you placed your fork and knife on the plate when you had finished eating, what you did with a fingerbowl; who walked through a door first, whose name was spoken first in an introduction, how others were addressed — black adults with just a first name, whites as "Mr." or "Mrs." — whose hand you shook and whose you didn't, who ate in the dining room and who in the kitchen. But to a young white child sorting through this array of behavioral rules and expectations, the dictates of racial etiquette hardly stood out from all the others.

Partly this was because the iron fist of prejudice in my 1950s Virginia was sheathed in the velvet glove of paternalism. I do not think I ever heard the word "nigger" as a child; I never witnessed any physical cruelty of whites towards blacks. The white adults around me treated "colored people" with what they considered to be good manners. Yet there was at the same time an undeniable assumption of superiority — of greater intelligence, of entitlement, of earned social position — that took its most pernicious and overt expression in occasions of humor or gentle mockery, disguised, or perhaps rationalized, as patronizing affection. When I became a historian and began to read about black and white interaction in the Old South of a century earlier, much seemed startlingly familiar.

No one talked openly about race in my family. It would have been considered rude — not unlike discussing sex, another prohibited topic. That the Supreme Court or Martin Luther King would raise such issues was above all a breach of decorum. Such rare references as I heard from my elders about the emerging civil-rights revolution consisted of clucking dismissals of impropriety and ill-mannered presumption. The elephant sat unmentioned in the living room. Even in the political arena, the discussion of race in Virginia was coded. Harry Byrd's program of massive resistance never directly invoked race or attacked blacks; instead he spoke of constitutional abstractions: of states' rights and federal encroachments.

Yet somehow I knew that, as with sex, talking about race was not just rude, but dangerous. When I asked Raphael about my school, I crossed both those lines — of propriety and of safety. To acknowledge race was the first step toward change. Raphael knew far better than I the dangers involved in any questioning of his place. But even at nine I knew enough to recognize my questions as a transgression.

Like a majority of white Virginians, my parents had voted for Eisenhower in 1952 and 1956. The solidly Democratic South was beginning to break apart, recognizing the Republican party as the more natural home for its conservatism. Harry Byrd had in a sense given his permission for such realignment, refusing to support Adlai Stevenson's Democratic presidential candidacy. When Eisenhower won election, Byrd hailed the new administration as a "ray of hope" that federal power and spending might be curbed.

I understood little of this in 1957, but I had been taken the preceding fall, as part of the 1956 campaign season, to an Eisenhower rally in nearby Middleburg. The candidate himself appeared, and although I remember nothing of what he said, the man's benevolent mien and generous smile made me glad to wear my "I Like Ike" button. I had seen the president; the White House had a human face; I could certainly write to him. I would address my letter to "Mr.," not "President," Eisenhower.

What surprised me most about the letter when I was reunited with it after more than 45 years was that the argument it offered against segregation was fundamentally a religious one. I had not remembered that at all. "Long ago on Christmas Day Jesus Christ was born. As you remember he was born to save the world ...Colored people aren't given a chance...So what if their skin is black? They still have feelings but most of all are God's people!" For years, I had told myself and others a quite different story about the sources and logic of my racial views. I thought that the combination of the merciless rationality and the political innocence of the child had led me to see the inconsistencies between the American creed of democracy and equality and the cruel realities of race in the mid-twentieth-century South. Perhaps I had been encouraged to make these assumptions about my motivations by the literature of southern history and by books like Gunnar Myrdal's 1944 classic An American Dilemma:The Negro Problem and Modern Democracy, which emphasized the emerging awareness after World War II of the contradictions inherent in American racial attitudes. I thought that the paradoxes of freedom and unfreedom that had plagued Virginians since the slaveowner Thomas Jefferson penned the Declaration of Independence had prompted me to understand — even as a nine-year-old — the hypocrisy of the white South. But my letter did not invoke American values; it assailed a different sort of hypocrisy. It was suffused with Christianity.

Perhaps I took this perspective because of the widely reported news of a declaration in early February 1957 from 60 of Richmond's Protestant clergy, who decried the sacrifice of the state's public school system "on the altar...of prejudice" and called for a "Judeo-Christian framework...of moral resolution" for the crisis. I certainly seemed to share their "Judeo-Christian" approach. But I have never thought of my childhood or my family as particularly religious. Ours was the detached faith of Episcopalianism, not the enthusiastic piety of the evangelical South. Talk about God was confined to Sunday-morning church, Sunday school, and a daily rendition of the Lord's Prayer — recited so fast at bedtime as to be almost one long word "whoartinheavenhallowedbethyname." Any other invocation of religion was almost as indecorous as discussing sex or race. We did not even say grace at meals. Yet here I was writing to the president demanding justice for "God's people."

Neither race nor the civil-rights movement was ever mentioned in our all-white local church. By the middle years of the 1960s my outrage at this stunning silence would lead me to abandon organized religion permanently. But in 1957 I was too young to notice how much less progressive our local minister seemed to be on the segregation question than many of Richmond's clergymen. When I learned much later about the colonial Virginia "right of advowson," which gave landowners effective control over the appointment and retention of clergy, I came to look upon the behavior of our rector, his failure to question the assumptions of the small circle of Clarke County residents who served as his vestry and set his salary, as part of a very long and ignoble tradition. His timidity and conformity, his failure to speak out against — perhaps even to see — twentieth-century racial injustice, were of a piece with the church's willful blindness — even complicity — in the establishment of slavery in the seventeenth century and in its defense up to the moment of its abolition.

Yet I imbibed some sort of egalitarian message from the church, nonetheless. Was it from the weekly Bible stories in Sunday school? The only one of these classes that I specifically recall was memorable for rather different reasons. One day, my father came to teach my class, substituting for the regular instructor — I think the minister's wife — who was sick. That Sunday's tale was Samson and Delilah. When we got to the end, my father asked if we children could identify the moral of the story. When no one supplied it, he offered his interpretation: "Never trust a woman." It seems Sunday school was no more likely to liberate my mind on questions of gender than of race.

Yet Christianity bore a message of freedom and justice and human worth that even the legacies of slavery and the inhumanity of segregation and racism could not silence. Jesus Christ, I informed Eisenhower, was born to save "not only white people but black yellow red and brown." In their segregated churches, white southern Christians sang:

In Christ there is no East or West

In Him no South or North;

But one great fellowship of love

Throughout the whole wide earth.

Join hands, then brothers of the faith

What e'er your race may be;

Who serves my Father as a son

Is surely kin to me.

In the leather-bound Common Prayer and Hymnal that I was given as a child, this is hymn 263. The words are attributed to "John Oxenham, 1908"; the notes appear above the stanzas on two treble staves marked simply "Negro Melody." Christianity in the mid-twentieth-century South, as in many other times and places, contained powerful ambiguities.

Slaves a century earlier had found in Christianity a message of self-affirmation and a promise of ultimate liberation that provided a critical foundation for community, identity, and survival. In the mid twentieth century, Christianity would serve as the weapon of the weak, an ideology for mass civil-rights activism, a lever of change that would make the transformation of southern race relations possible. Martin Luther King's effectiveness depended on the existence of thousands of Americans like me who could be confronted with the contradictions between their fundamental religious and moral commitments and their participation in the South's systems of racial oppression.

In his famous "Letter from Birmingham Jail," written in 1963, King articulated his challenge to the Christian South to live up to its professed ideals. "The contemporary Church is so often a weak, ineffectual voice with an uncertain sound....It is so often the arch supporter of the status quo....But the judgment of God is upon the Church as never before. If the Church of today does not recapture the sacrificial spirit of the early Church, it will lose its authentic ring, forfeit the loyalty of millions....I hope the Church...will meet the challenge of this decisive hour."

King explained the strategy that had shaped his efforts in Montgomery, in Albany, and in Birmingham. His movement depended on its appeal to "the light of human conscience" and its commitment to ending the silence of consent to the status quo. "Nonviolent direct action seeks to create such a crisis...that a community...is forced to confront the issue. It seeks so to dramatize the issue that it can no longer be ignored."

As I grew older, King would successfully appeal to my conscience. I am not sure what, if anything, I knew of his efforts in Montgomery when I wrote to Eisenhower in 1957. But his message spoke to exactly the sentiments that prompted my letter. And it was these same sentiments that encouraged me, by my later years in high school, to get involved with Quaker activists and to spend the summer of 1964 on a civil-rights initiative in Orangeburg, Atlanta, and Birmingham. Eight years after I wrote President Eisenhower, I responded to Martin Luther King's dramatization of the injustices at Selma in exactly the way he hoped and intended. Like thousands of other Americans, I found the television images of Bloody Sunday on Selma's Edmund Pettus Bridge intolerable. I could not stand by as peaceful citizens were clubbed and gassed as they marched for the right to vote. A college freshman, I cut my spring midterms and went to Selma. As with my letter to Eisenhower, I never told my parents. Even as I differed from them on issues of race and civil rights, I seem to have been less successful in challenging their rules about silences. For all the changes that came to Virginia and the world in the sixties and afterwards, we still never talked openly about race, religion, or sex.

The nine-year-old writer closes her letter with emotion, as if the effort to advance the logic of her position has for a full page only just managed to contain the intense "feelings about segregation" she described in the first paragraph. "Please Mr. Eisenhower please try and have schools and other things accept colored people." This letter takes its place within the tradition of entreaties and petitions from women to their rulers. Indeed it was within the nineteenth-century abolition movement that American women's right to petition was first forcefully expressed, as between 1831 and the Civil War women sent three million signatures to Congress pleading for the end of slavery. In 1863, Susan B. Anthony defined the petition as woman's most important political right. "Women," she observed, "can neither take the ballot or the bullet....Therefore, to us, the right of petition is one sacred right which we ought not to neglect." Like all American women until the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment in 1920, just 37 years earlier, this nine-year-old letter-writer cannot vote. She is, of course, too young. But that means that, like generations of women who preceded her, she has no political power to exert, no threat to offer, no reward to promise any elected official. She can only plead. This injustice matters to me, she writes, even though I am only nine, even though I am white and it is not being done to me.

Why did it matter so much? Was the injustice in some sense being done to me? There was, of course, a long tradition of white southern opposition to slavery that insisted slavery harmed whites more than blacks. Jefferson himself made this argument. But there is no evidence that I was thinking about segregation in this way. Yet I find something curious and perhaps revealing about the letter's signature. "Sincerly." I was a good speller. This is my one slip. But my name is out of alignment. It looks as if I wrote Drew Gilpin, which was indeed what I was called. And then I decided I should include my real first name, which I never used except to identify myself as female. So "Catharine" is added in front — sticking out from the 'Sincerly" and looking quite out of place. I wanted to be known not just as nine and white but as a girl. I am sure that had I not added the "Catharine," the response from the White House would have come to Mr. Gilpin; the description of the letter in the Eisenhower Library catalog would note that "Mr. Gilpin expresses his feelings...." I had begun to learn the realities of having a male name even by the age of nine; I knew I had to take action to claim my femaleness and my own identity. I wanted to speak to Eisenhower as the person I was, and clearly I saw part of that as being a girl.

Did being a girl have a more general importance to the letter and to my "feelings about segregation?" I have often wondered this as I have thought about the years that followed. I was the only daughter in a family of four children; I was the rebel who did not just march for civil rights and against the Vietnam War, but who fought endlessly with my mother, refusing to accept her insistence that "This is a man's world, sweetie, and the sooner you learn that the better off you'll be." Did my sense of the privileges allotted my brothers — who did not have to wear scratchy organdy dresses or lace underwear, sit decorously, curtsy, or accept innumerable other constraints on freedom — make me attuned to other sorts of injustice? I grew up in a man's world and a white world. Did I somehow see a connection between the two? The women's movement would certainly help me to make these connections many years later. But I did not have the language or analytic framework to articulate such insights until after I graduated from college. It is extraordinary what one doesn't see. Or perhaps on some level I did see, and the sense of my own place in my family and in the Virginia social order did make me sensitive to the place of others.

The public schools in Clarke County were not integrated until 1966. The vagueness of the Supreme Court's demand for "all deliberate speed" became an ironic betrayal of so many of the civil-rights movement's hopes. By 1966, I was a junior in college in Pennsylvania. I rarely returned to Virginia — from school or, indeed, ever again. I found its silences both too difficult to maintain and too difficult to challenge. I would wrestle with the dilemmas of race that had suffused my childhood from a distance of both time and space. Living my life north of the Mason-Dixon line, I abandoned activism for history, telling myself that I was searching in the nineteenth-century South's experiences of slavery and war for the understanding that might somehow contribute to change.

At the core of the questions I wanted to ask about the past was the desire to comprehend how human beings become so imbedded in the taken-for-grantedness of their world that they cannot see it clearly, how people come not just to accept but to defend slavery or segregation — or any of a host of other insupportable injustices. If we understand how others have failed to see or failed to speak, perhaps, I thought, we can come to recognize our own blindnesses, our own processes of rationalization and self-justification. Perhaps history can help us to see the contingency of our lives, our beliefs, and our social worlds. Perhaps history can help us understand that it could have been, we could have been, we could still be otherwise. In history we might find a sense of possibility.

But as I think of my nine-year-old self, I am acutely aware as well of the opportunities given — or denied — by specific historical moments. I wrote my letter because the radio, the newspapers, the Richmond clergy, the Supreme Court, the NAACP had begun to break the silence. Had I been born a decade earlier, I would never have asked those questions, written that letter, or been privileged to lead what has become my life. My actions — my letter, my protests, my marches — mattered very little to the cause of racial justice in the twentieth-century South; but they freed me: to speak, to see, and to escape from a world of dehumanizing silence.

Drew Gilpin Faust is professor of history, professor of Afro-American studies, and dean of the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study. This article was written for a collection of autobiographical essays by southern historians entitled Shapers of Southern History, to be published by the University of Georgia Press in 2004, and appears in this magazine with the editors' thanks.