Poet August Kleinzahler and orator Linda Greenhouse ’68, speaking in Sanders Theatre, launched the Memorial Day-shortened Commencement week at the 223rd Phi Beta Kappa literary exercises for the College on Tuesday morning, May 28. The much-honored Kleinzahler has a reputation as a pugnacious poet rooted in his home ground of Fort Lee, New Jersey, and his adopted home of San Francisco; Greenhouse is a Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist and author, renowned for her decades covering the U.S. Supreme Court for The New York Times and in books since leaving that position in 2008. (For detailed background on each, see “Bicoastal Poet, Beat Reporter.”)

Kleinzahler read three richly figured poems from his 2008 collection, Sleeping It Off in Rapid City. Greenhouse drew on her experience as Chief Marshal in 1993—when General Colin Powell was the Commencement speaker and gay rights became a more prominent public issue—to engage her audience in understanding the changes in American society and the court's role in those changes. (The poems and the oration appear as sidebars alongside this report.)

In the formal Alpha Iota Chapter business that preceded the poems and oration, president Logan McCarty (director of physical-sciences education, lecturer on chemistry and chemical biology, and lecturer on physics) oversaw the ceremonies. The Reverend Daniel Smith, lecturer on ministry (he teaches “Introduction to Public Preaching”) and affiliated minister in the Memorial Church, offered the invocation. The music—Randall Thompson’s “Felices Ter” (“Thrice happy they,” based on Horace’s Odes I, 13; 17-20, and inscribed on Harvard Yard’s Holyoke gate) and Franz Joseph Haydn’s “Stimmt an Die Saiten” (“Awake the Harps,” from The Creation)—was performed by the Harvard-Radcliffe Collegium Musicum, conducted by Andrew G. Clark, director of choral music.

In his introduction, McCarty touched on a drama about which most of the audience was presumably unaware. He began by addressing “Madam President [Drew Faust], Dean Hammonds….” Only minutes before, as she was putting on her academic gown for the ceremony, Harvard College dean Evelynn M. Hammonds's forthcoming departure from her office, at the end of the term, was announced. Thus, this was both a welcoming comment and a valedictory one, as Hammonds will preside over Commencement exercises involving College students for the last time this week.

McCarty traced Phi Beta Kappa's origins to William and Mary College, at the outset of the American Revolution, and said that through the centuries, its purpose—to promulgate “philosophy,” or in modern terms, "critical thinking," as the guide to living life—had remained important and intact. He then said the chapter would recognize guests who had conducted their lives guided by such a map.

Honorary Members

As it does annually, the chapter conferred honorary memberships on College alumni from the fiftieth-reunion class—people who have led lives marked by distinguished achievement and intellectual pursuits—plus retiring faculty members known for distinction in their fields and for mentoring students. Daniel Donoghue, Marquand professor of English, recognized these recipients:

Photograph by Jim Harrison

His Excellency the Right Honorable David Johnston

Photograph by Jim Harrison

Steven Lubin

Photograph by Jim Harrison

Frederica Drinkwater Perera

Photograph by Jim Harrison

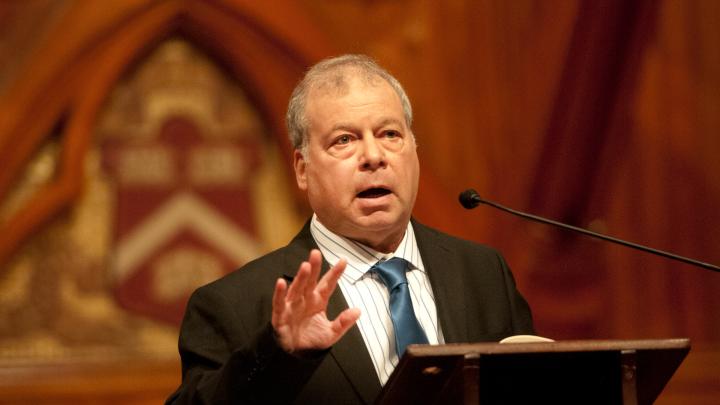

Robert D. Reischauer

Photograph by Jim Harrison

Christopher Sims

Photograph by Jim Harrison

Gurcharan Das

Photograph by Jim Harrison

Joaquim-Francisco Coelho

Photograph by Kris Snibbe/Harvard News Office

Stanley Hoffmann

Photograph by Jim Harrison

Michael O. Rabin

- His Excellency the Right Honorable David Johnston ’63, Governor General of Canada, a former hockey player elected to Harvard’s Athletic Hall of Fame, twice an All-American despite his Canadian origins, law professor, dean of the faculty of law at the University of Western Ontario, and principal and vice-chancellor of McGill University. He served as fifth president of the University of Waterloo, and was the first non-American president of Harvard’s Board of Overseers, the University’s junior governing board, in the 1997-1998 academic year. He became the twenty-eighth governor general in October 2010.

- Steven Lubin ’63, pianist and fortepianist, who has taught at Cornell, Vassar, and the Juilliard School. He is now professor of music at the conservatory of music at Purchase College. (Lubin will give a concert of Mozart works tomorrow at 1:15 p.m. in Sanders Theatre.)

- Frederica Drinkwater Perera ’63, professor of environmental health sciences at Columbia’s Mailman School of Public Health, where she directs the center for children’s environmental health. A pioneer in the field of molecular epidemiology, she is also a lifelong learner, Donoghue noted: she added a Ph.D. to her other educational attainments only last year.

- Robert D. Reischauer ’63, Senior Fellow of the Harvard Corporation, the University’s senior governing board, who has overseen its modernization and expansion during a period of reform formally unveiled in late 2010. Reischauer is past president of the Urban Institute and served as director of the Congressional Budget Office from 1989 to 1995. Donoghue said Reischauer had been a “public intellectual at the service of the public good.”

- Christopher Sims ’63, Ph.D. ’68, econometrician, now Helm professor of economics and banking at Princeton and 2011 co-Nobel laureate in economic science. He has explored important connections between information theory and economics.

- Gurcharan Das ’63, AMP ’91, retired business leader and now author of a blog, whose books include India Unbound, and newspaper columns. A philosophy concentrator, Donoghue noted, Das wrote his thesis under the guidance of John Rawls, author of the magisterial A Theory of Justice.

- Joaquim-Francisco Coelho, Smith professor of the language and literature of Portugal and professor of comparative literature. Donoghue noted that a colleague called Coelho a “gem,” and cited his scholarship on Portuguese poetry of every era, and his own original poems in the language.

- Stanley Hoffmann, A.M. ’52, Buttenwieser University Professor (profiled in Harvard Magazine’s “Le Professeur”). Hoffmann has completed a half-century on the faculty, Donoghue noted; illness unfortunately kept him from attending the ceremony.

- Michael O. Rabin, Watson Research Professor of computer science. The winner of every major prize in computer science, Rabin remains active investigating important problems in encryption, privacy, and security, Donoghue noted.

- August Kleinzahler, the poet.

Photograph by Jim Harrison

Jacob Barandes

Photograph by Jim Harrison

Stephen Blyth

Photograph by Jim Harrison

Amanda Claybaugh

Teaching Prizes

POPE PROFESSOR of the Latin language and literature Richard Tarrant, who also coaches the student orators who speak in Tercentenary Theatre during the Morning Exercises on Commencement day—as shown in action in 2012—presented the Phi Beta Kappa teaching prizes on recipients chosen from the pool of candidates nominated by the PBK undergraduates themselves. The recipients this year were:

Jacob Barandes, Ph.D. ’11, lecturer on physics and associate director of graduate studies, who teaches Physics 210, “General Theory of Relativity,” and Physics 232, “Advanced Classical Electromagnetism.” His nomination cited his “ability to explain even the most complex technicalities” in clear, simple language, and to convey “a broad and unified picture of physics.”

Stephen Blyth, Ph.D. ’92, professor of the practice in statistics, who is also managing director of Harvard Management Company (HMC), where he oversees public markets and is among the top-performing endowment portfolio managers. He teaches Statistics 123, “Applied Quantitative Finance on Wall Street.” According to his nomination, Blyth brings “mathematical rigor with a rich store of real-world experience” to the study of finance, and enriches his teaching by having students operate simulated portfolios in which they execute trades.

Amanda Claybaugh, Ph.D. ’01, professor of English, who studies nineteenth-century American literature, Victorian literature, and trans-Atlantic literary relations. (Read the magazine’s Harvard Portrait of Claybaugh here.) She was cited for “bring[ing] the tools of literary criticism to bear on contemporary writers, and invit[ing] her students to read the latest Jonathan Franzen novel with the same degree of attention they would apply to Dickens or Bronte." Her innovative teaching methods include having students compose not only conventional analytical essays, but also assessments in the form of book reviews. “She makes the study of English come alive,” her nomination continued, "by treating the writing of the present with respect and by showing the classics to be fresh and relevant." The quotes in this paragraph are updated and corrected May 28 at 4:40 p.m.

The Poet: “At the heart of the heart of America”

August Kleinzahler—born in Jersey City and raised in Fort Lee, New Jersey; educated at the Horace Mann School in New York City, the University of Wisconsin, and the University of Victoria, in British Columbia; and now a resident of San Francisco—has been honored for his many books of poetry with a Guggenheim Fellowship, an American Academy of Arts and Letters Award in Literature, and a Berlin Prize Fellowship. Chapter vice president and president-elect Ann Pearson, Ross professor of environmental sciences, calling him “an American poet to whom a sense of place is foremost,” cited his reputation for modernist language employed in the service of precise poetics. The most recent of his 10 volumes of poems, Sleeping It Off in Rapid City (2008), collecting earlier poems and new work, won the National Book Critics Circle Award.

An animated and expressive reader—complete with vivid renderings of a hawk's harsh cries—Kleinzahler read three poems from that collection: “Sleeping It Off in Rapid City,” “The Hereafter,” and “Anniversary.” (The poems are also available in the sidebar link at the upper right alongside this report.)

The first, written from “The dead solid center of the universe/At the heart of the heart of America,” is laced with Kleinzahler’s characteristic profusion of precise details, in which he is deeply immersed even as he seems alienated from them:

The Lord’s blessing is everywhere to be found

The Lambs of Christ are among us

You can tell by the billboards

The billboards with fetuses, out there on the highway

Through the buzzing, sodium-lit night

Semis grind it out on the Interstate

Hauling toothpaste, wheels of Muenster, rapeseed oil

Blessed is the abundance, blessed the commerce

Across the Cretaceous hogback

Hundred million year old Lakota sandstone, clays, shale, gypsum

And down through the basins of ancient seabeds

Past the souvenir shops and empty missile silos

The ghosts of 98 foot long Titans and Minutemen

150,000 pounds of thrust

Stainless steel, nickel-alloy-coated warheads

Quartz ceramic warheads, webbed in metal honeycomb

8 metagon payloads

Range 6,300 miles

Noli me tangere

God bless America

We’re right on top of it, baby

“Anniversary” shows this urbanite equally adept at observing natural detail. It begins:

You’d figure the hawk for an isolate thing,

Commanding the empyrean,

Taking his ease in the thermals and wind

Until that retinal flick, the plunge and shriek—

cruelly perfect at what he is.

The Orator: “Wounds that for too long had gone unacknowledged were at last being recognized and healed.”

Linda Greenhouse has perhaps set a record for serving as the all-occasion Harvard speaker and citizen, even before her PBK oration. Among her engagements:

- She was elected to the Board of Overseers in 2009.

- She appeared on the Radcliffe Day panel, “From Front Line to High Courts: The Law and Social Change,” during Commencement week 2012, and moderated a Radcliffe panel on “Gender and the Law: Unintended Consequences, Unsettled Questions” in 2009.

- In 2006, she was awarded the Radcliffe Institute Medal, its highest honor, and was the featured speaker at the institute’s luncheon.

Just last Thursday, she was among the speakers at the Memorial Church service for Anthony Lewis’48, NF ’57, who pioneered the Supreme Court coverage at The New York Times and elsewhere, to which Greenhouse became the lauded successor. In 1993, she was elected Chief Marshal of her class’s twenty-fifth reunion—an experience that figured prominently on her oration, itself the occasion for Greenhouse’s return to Sanders Theatre to complete another Crimson circle: she graduated as a member of Phi Beta Kappa 45 years ago.

“The Sentence and the Parenthesis,” as the oration is titled (it also appears in the sidebar, above), perhaps spoke more directly to the students attending than some prior orations have done. Greenhouse began by drawing on Sonia Sotomayor’s recent memoir, in which the author, now a Supreme Court justice, recalled that when she was elected to Phi Beta Kappa at Princeton, she had not even known what it was, and had thrown away the letter of notification as “some junk mail from some club.” Greenhouse contrasted Sotomayor’s experiences with her own at Harvard College, coming from a middle-class family with college-educated parents. She then drew on the experience of Justice Harry Blackmun (Greenhouse published a biography of the justice in 2005), who had expected to attend the University of Minnesota, but instead was diverted east when the Harvard Club in that state gave him a $250 annual scholarship and a $100 loan, to cover his tuition in Cambridge (at the rates prevailing in the 1920s). “In four years,” she noted, “Harry Blackmun could never afford to go home over the Christmas vacation.” He studied hard, made PBK, and graduated summa cum laude in mathematics.

Greenhouse then said that her review of recent orations revealed that “most of them have dealt with high questions of policy rather than personality,” and that she had settled on a different approach—one that drew on her experience—a decisive moment at Harvard that foreshadowed larger issues in American society.

This was not the first time she had spoken from the Sanders stage, she said:

Twenty years ago, I was the chief marshal of the 1993 Harvard Commencement, an office bestowed every year on a member of the twenty-fifth reunion class. The Commencement speaker and chief honorary degree recipient that year was General Colin Powell, at the time the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. In the aftermath of the Gulf War, Harvard was honoring General Powell not only for his military accomplishments but for his great American life story.

In the interval between General Powell’s selection and the approach of Commencement, something had happened. The question of gays in the military had become a matter of raging political controversy, and Congress, with the support of General Powell and President Clinton, had adopted the much-despised and, in retrospect, preposterous “don’t ask, don’t tell” policy. This policy permitted gay men and lesbians to serve only so long as they kept secret an essential part of their personal identity.

Beyond regarding the policy as silly, I had not given it a lot of thought by the time I started getting calls from classmates after General Powell’s selection had been announced. I knew some of these classmates, but not most of them. I’m gay, these classmates told me. And they asked: How can I possibly participate in a ceremony honoring someone who embodies a policy that withholds dignity and respect from men and women who want only to serve their country? How can I enjoy my reunion?

These calls were remarkable because I had never had a personal conversation of any kind with these callers. As I perhaps need to remind younger members of the audience, most gay people were not out to near strangers in 1993. Certainly back in our college days, a number of gay classmates were not yet out to themselves or, if they were, didn’t casually share this information with others. So the calls I was getting reflected a degree of pain and urgency that I couldn’t ignore. It just seemed unthinkable that classmates would feel excluded from their own twenty-fifth reunion, and I was certain that Harvard had not anticipated or intended anything like this result when it chose to honor Colin Powell.

So I turned to my friend Margaret Marshall, who was then Harvard’s general counsel [and was married to Anthony Lewis; in 2003, as Chief Justice of the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court, she wrote the majority opinion in Goodridge v. Department of Public Health that recognized same-sex marriage in the Commonwealth]. She and President Neil Rudenstine let it be known that they were sympathetic to the dismay of my classmates and of others who were expressing similar reactions. The Harvard administration opened its door to anyone who wanted to come in and talk about the situation and about what type of public display at Commencement might be appropriate. The administration let it be known that a public protest at Commencement would be acceptable, as long as it was civil and non-disruptive.

Against this background, my classmates gathered for the week-long reunion. Of course, classmates without a personal stake in the issue were generally unaware of what had been taking place. Gay members of the class engaged others in serious conversation. For many straight members of the class, it was the first time they had participated in such conversations. Don’t forget that Lawrence v. Texas, the Supreme Court decision that freed homosexuality from the stigma of criminalization, was still a decade in the future.

One of my more pleasant duties as chief marshal was to select classmates to be invited to the lunch preceding the afternoon Commencement exercises. I invited one of my very out classmates, who arrived in his top hat and tails, festooned with banners and buttons proclaiming the gay-rights cause and denouncing “don’t ask, don’t tell.” He went up to Colin Powell, whose uniform was festooned with a general’s stars and medals. What a picture this pair made. “General Powell,” my classmate said, “I look forward to the day when this issue no longer divides us.”

It was a gutsy move. For all my classmate knew, General Powell would spurn him, cut him dead. Instead, the general embraced him with both arms, and replied: “So do I, and I hope that day comes sooner rather than later.” My classmate was so taken aback and touched by this response that he had tears in his eyes as he recounted it to me. Word of the encounter spread quickly among the gay community as the crowd gathered in Tercentenary Theatre that afternoon for General Powell’s speech. The mood had shifted: the anxiety and incipient anger were gone. When General Powell got up to speak, some of my classmates stood in silent, dignified protest. The general acknowledged them graciously. What might have been an experience of pain and isolation became instead one of solidarity and community. [Read Harvard Magazine's coverage of the 1993 Commencement exercises, including General Powell's address and the protest, here. It is also available in the sidebar, above].

All these years later, that week remains one of the most vivid experiences of my life. I saw connections being made among people who, while they had a Harvard degree in common, had been in a basic sense strangers to one another as they moved through adulthood. It seemed to me that as we stood on the cusp of middle age, wounds that for too long had gone unacknowledged were at last being recognized and healed. At the close of that reunion week, when I was invited to this stage to say a few parting words, I said that Harvard, without the slightest intent, and through an accident of history, had nonetheless managed to bring us together in a way that no one could have scripted and no one would ever forget. We were, as always, but in a new way, in Harvard’s debt.

Greenhouse reflected on that experience, and others, to categorize the ebbs and flows—the sentences and parentheses—as America, and its Supreme Court, work their way through periods of social progress and of pauses, consolidations, or even, in her view, regressions. Considering the court’s role as a leader or follower, she said, “it seems to me that it’s one thing to refrain from leading, and another to reach out to unravel settlements reached elsewhere in the political system, settlements by which we have agreed to live with one another in a complex and increasingly diverse society.”

At the conclusion of the exercises, Reverend Smith gave the benediction.