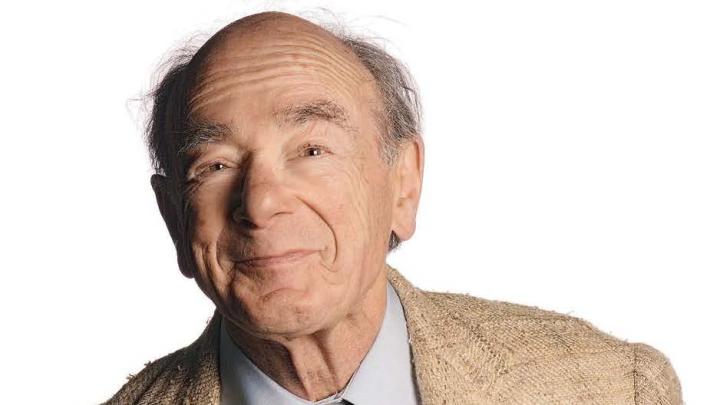

Buttenwieser University Professor emeritus Stanley Hoffmann, a renowned scholar of international relations, American foreign policy, and French and European politics who spent his early teens hiding from the Gestapo in Vichy France, died in Cambridge on September 13 after a long illness. During his 58 years on the Harvard faculty, beginning in 1955 as an instructor in the department of government, he helped found the honors undergraduate concentration Social Studies (1960), served as founding chairman of what became the Gunzburg Center for European Studies (1969), taught legendary courses on “War” and “Political Doctrines and Society: Modern France” to thousands of undergraduates, and mentored hundreds of doctoral students.

As a teacher drawing on his own scholarship, he also helped hold the University together. In April 1969, during the tense meeting in Memorial Church that followed the police bust of students occupying University Hall, he was one of the speakers who addressed the packed crowd of students and faculty members working their way toward a plan of action. “This is the only university we’ve got,” he reminded them. “It can be improved, it should be improved, but it should not be destroyed.…There is a need for changing the decision-making structure, but no structure, however perfect, will guarantee that views of a minority become the majority, and no university can function if a minority insists on winning all the time.”

~ The Editors

In Vichy France, there were few diversions; among them were Hollywood musicals and comedies, such as those starring Fred Astaire and Bing Crosby, which helped lift the spirits of French audiences. One great success was Frank Capra’s Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, the story of a decent, average citizen who unexpectedly finds himself in the U.S. Senate, where he stubbornly persists in his ultimately victorious fight against a corrupt group in power. Although they controlled much of daily life, the German occupiers could not stop the French audiences from identifying with James Stewart as Mr. Smith. “They came to applaud,” says Stanley Hoffmann, who as a young boy was among those applauding.

Now 78 years old, Hoffmann has been, since 1997, Buttenwieser University Professor; he ranks as one of the world’s preeminent authorities on international relations, with specialties in French politics and history and American foreign policy. He has written 18 books and countless articles, including, since 1978, regular essays in the New York Review of Books. Having taught at Harvard since 1955, Hoffmann also founded what is now the University’s Gunzburg Center for European Studies (where his recorded voice greets callers) and was among those who created the social-studies concentration in the College. “He probably holds the record for the greatest number of different courses taught in Harvard’s Core curriculum,” says Bass professor of government Michael Sandel, who has known Hoffmann for more than 30 years, taught a course on globalization with him, and calls him a “towering figure. Stanley has voracious intellectual interests and a range of knowledge of politics, history, and culture that is unrivaled in the academic world, as far as I know.”

Rarely does a scholar’s life show such an intimate connection between personal experiences and academic pursuits as Hoffmann’s does. “It wasn’t I who chose to study world politics,” he wrote in a memoir published in a 1993 festschrift, Ideas and Ideals: Essays on Politics in Honor of Stanley Hoffmann. “World politics forced themselves on me at a very early age.”

Born in Vienna in 1928, he grew up in the early 1930s in Nice, France, with his Austrian mother (his distant American father returned to the States and had scant contact with his son thereafter). “Nice was filled with foreigners,” he recalls. “Russian migrs, people from Central Europe who had retired to the Riviera.” In 1936 Hoffmann mre et fils moved to Paris. “My mother thought the schools would be tougher there,” Hoffmann says. “She was right. For me, it was like moving from paradise to purgatory: the sky was gray, there was no sea, and Hitler was beginning to spread his wings.” On May 10, 1940, acute appendicitis afflicted the boy just as the radio reported the German attack on Belgium, Holland, and France. “I was under the knife in between air raid sirens,” he wrote.

Hoffmann was baptized at birth as a Protestant, but his anti-clerical mother’s family fit the Nazi racial definition of Jews, and so the two of them, essentially stateless people, fled Paris. “My mother and I were two small dots in that incredible and mindless mass of ten million people clogging the roads of France,” he wrote. They finally reached Lamalou-les-bains, a tiny spa in Languedoc—and then, as the school year began, they returned to Nice, by then part of Vichy France. Once they left Paris, “my fate had become inseparable from that of the French,” Hoffmann wrote. “It wasn’t simply the discovery of the way in which public affairs take over private lives, in which individual fates are blown around like leaves in a storm once History strikes, that had marked me forever. It was also a purely personal sense of solidarity with the other victims of History and Hitler with whom we had shared this primal experience of free fall.”

In Nice, after the Germans occupied the city in September 1942, the Gestapo were around every corner. “It was three months of waiting for the bell to ring at 3 a.m.,” he recalls. “Fear never left us.” And the little family had almost no resources; Hoffmann’s mother sold her jewels and borrowed from a friend, though in the empty markets there wasn’t much to eat anyway. Although they remained without citizenship through the war, “I had one great advantage: I was a very good student,” he says. “The French were willing to forgive anybody anything if one was a good student and spoke good French.” But excursions to enjoy the music, films, and walks that the studious Hoffmann loved were made hazardous by the sudden rafles, police and Gestapo round-ups such as the one in which his only close friend, the French-born son of Hungarian Jewish migrs, disappeared, with his mother, forever.

Carrying French documents that his history teacher had forged for them, Hoffmann and his mother returned to Lamalou-les-bains on a blacked-out night train. There, they found that 1,000 young German soldiers had encamped in the village of 800. The two groups didn’t speak to each other, but there was no Gestapo, it was perfectly safe, and there was no more fear. The villagers somehow found places for them to stay, even if it meant frequent moves as the Germans kept occupying hotels. “There was a basic decency in those French people,” he says, adding a quote from The Plague by Camus, “There is more in man to be admired than condemned.”

Throughout their ordeal, the kindness and protectiveness of so many French countrymen and teachers made an indelible impression and stamped Hoffmann as irretrievably French. The voices of the Free French and General de Gaulle on the BBC helped sustain the hope “that kept one’s soul from freezing,” he wrote. But it was not until 1972, in a review of The Sorrow and the Pity, the Marcel Ophuls film on the Occupation, that Hoffmann spoke publicly of his wartime experiences; he ended the review by recalling the compassionate history teacher who had helped their flight from Nice: “He and his wife were not Resistance heroes, but if there is an average Frenchman, it was this man who was representative of his nation; for that, France and the French will always deserve our tribute, and have my love.”

In 1944, the Lamalou-les-bains villagers flocked to see the first newsreels of the liberation of Paris. Hoffmann, who got his first look at the “tall and imperturbable” de Gaulle, has never forgotten the exhilaration of that moment. The “euphoria of a national general will was palpable,” he wrote, adding, “For the rest of my life, I was going to be stirred by the drama of peoples rising for their freedom, or breaking their chains, more deeply than by any other public emotion and by most private ones.”

Despite his prodigious scholarly output, it is difficult to categorize Hoffmann’s approach to international relations. “There is no ‘school of Hoffmann’—he doesn’t have doctrinal disciples,” says Michael J. Smith ’73, Ph.D. ’82, Sorensen professor of political and social thought at the University of Virginia, who studied with Hoffmann and later co-taught a course with him. “Stanley has a horror of mimesis; he doesn’t want you to ape what he thinks—his students are the polar opposite of ‘dittoheads.’ They aren’t people who share a set of conclusions; they share a mode of inquiry, and come to their own conclusions using the best available arguments.”

Hoffmann also is hostile to radical cures, allergic to communism and Marxism, and in fact profoundly “suspicious of anything that smacks of utopia and ideology, of a grand vision for the People with a capital P, or any millennial movement,” says his student Ellen Frost ’66, Ph.D. ’72, an international-relations scholar and former U.S. government official. (Hoffmann himself cites the French philosopher and political scientist Raymond Aron, a critic of French leftists, as a mentor, and calls him “a great anti-utopian.” Hoffmann writes that, like Aron, he naturally tends to “think against,” noting that he has had the “intellectual romps of a fox, and the convictions of a hedgehog.”)

Furthermore, Hoffmann has never been tempted by government service, either as a policy adviser or bureaucrat, explaining that he is temperamentally unsuited for such work and values his independence too highly. “When I’m in Washington, I want to take the next plane out of there,” he says. “People who come back from this Washington world take a good time to become normal again.” He observes that he has remained “too French to be a convincing American policymaker,” adding, with characteristic wit, that his Harvard contemporaries Henry Kissinger ’50, Ph.D. ’54, and Zbigniew Brzezinski, Ph.D. ’53, didn’t have this problem. And unlike those two, “[M]y reaction to power is more dread than desire,” Hoffmann writes. “I study power so as to understand the enemy, not so as better to be able to exert it.”

Hoffmann’s analysis of American politics may be “more influential overseas than it is here,” says Louise Richardson, Ph.D. ’89, executive dean of the Radcliffe Institute, a former Hoffmann student who studies terrorism. “He is humanistic, and he brings history into the equation and focuses on the importance of individual leaders.” (De Gaulle is his personal hero.) This approach, which eschews the quantitative data and theoretical models now fashionable in international relations, nonetheless, in Hoffmann’s hands, produces astonishingly insightful analyses. “He has an old-fashioned approach to the study of politics that emphasizes history, diplomacy, and political philosophy,” says Sandel. “Some might accuse Stanley of being a dinosaur, but if that’s true, then more of us should aspire to be dinosaurs.”

“He’s been prescient—and right—on all the major issues of the postwar period,” says Smith. Hoffmann opposed the French war in Algeria and supported de Gaulle’s efforts to extricate the French from their colonial past there. In 1963, when John F. Kennedy was commander-in-chief, Hoffmann predicted that the Vietnam War would prove an exercise in futility (and in his memoirs, Pentagon Papers source Daniel Ellsberg ’52, JF ’59, Ph.D. ’63, credits Hoffmann with changing his mind on Vietnam—the two debated at Radcliffe in 1965). In 1975, Hoffmann wrote an article recommending a new foreign policy for Israel to advance the cause of peace there, an essay that he says he could republish today without changing a single word (“At least half” of terrorism would disappear, he believes, if the Israel/Palestine conflict were resolved). And in March 2003, Hoffmann wrote an essay in the Boston Globe on the eve of the invasion of Iraq; all of its gloomy predictions have since come true. In 2004 he advocated a phased military withdrawal from Iraq, an idea that seemed outr at the time but that has since been backed by a majority in Congress.

Experience and learning have combined in Hoffmann to produce a singular outlook on world politics. Start with a brilliant intellect: he graduated at the top of his class at the Institut d’tudes Politiques (“Sciences Po”) in 1948 and received tenure at Harvard in 1959, only four years after joining the faculty. And in the life of the mind, powerful ideas often come from those who reside both inside and outside some discipline or community; they combine the fresh eyes of the outsider with the deep knowledge of a participant.

Hoffmann considers himself someone whose nature, choices, and fate have made him “marginal in almost every way.” Having spent his formative years in France, he has now lived in the United States for twice as long as he did there, and has been a citizen of both countries since 1960. His writings, while often critical of American foreign policy, also aim to support the United States in living with greater security and respect in the world. He often provides perspectives that are unavailable to those (there are many) who lack his worldliness and deep historical knowledge.

Take, for example, McGeorge Bundy, JF ’48, LL.D. ’61, a former dean of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences and an admired friend, who Hoffmann says “shared the belief of all who have been in the U.S. foreign policy establishment: that America could do practically anything it wanted, because of its combination of force and wisdom.” When Bundy, as national security adviser in the Kennedy administration, was helping to mount the Vietnam War, he had a correspondence with Hoffmann in which the latter questioned whether the United States could succeed in this venture, arguing in part from the French experience in the region. Bundy replied, “We are not the French—we are coming as liberators, not colonialists.” “The only problem,” Hoffmann says, “was the Vietnamese.” He adds that American foreign policy tends to commit “the sin of excessive benevolence: we will make people happy whether they want it or not.”

Americans, he feels, “have to understand the foreignness of foreigners, instead of believing that they are simply misguided Americans or not well-guided Americans.” Even Zbigniew Brzezinski, he notes, “still has this conception that the United States can make decisions for everybody.” Recently, at a Faculty of Arts and Sciences meeting on general education, a young economist rose to declare that people everywhere are pretty much the same and want the same things, so the one course that all undergraduates ought to take is economics. “I exploded,” Hoffmann recalls, “and said, ‘This is why we have been so successful in Vietnam and Iraq.’ The assumption that ‘people everywhere are all alike’ is something you have to get out of your system. In old age, I am more and more convinced that people are intensely different from country to country. Not everyone is motivated by the same things.

“Americans mean well, but they don’t understand that acting with all one’s might to do good can be seen as a form of imperialism,” Hoffmann continues. “Within 10 minutes, these good intentions can turn into a benevolent condescending attitude toward the lesser tribes.”

In one of his early books on U.S. foreign policy, Gulliver’s Troubles (1968), Hoffmann deploys the metaphor of a giant besieged by tiny adversaries who nonetheless fetter him effectively. An apt analogy to the United States’s predicament 40 years ago, it appears nearly oracular today, when there is daily proof that, as Hoffmann says, “Populations with even a small number of rebels can make large armies ineffective.” (His 2004 sequel with Frdric Bozo, Gulliver Unbound: America’s Imperial Temptation and the War in Iraq, argues that the United States blunders into snares when it lumbers forward, heedless of foreign nations’ histories and indigenous sentiments.) “The people surrounding Paul Bremer [M.B.A. ’66, head of the provisional authority governing Iraq in 2003-04] had never been in the Mideast and knew nothing of the region,” Hoffmann says.

The years since 2001 “have shown the absolute fiasco of unilateralism,” he declares. “We make reality, but if we make it alone, it will boomerang.” The United States seemingly needs to relearn expensive lessons it has already paid for, and forgets things it used to know. “In 1945 and in the immediate postwar period, the United States did respect, within limits, what Europeans wanted,” Hoffmann explains. “We had an enemy, the Soviet Union, which was repressing its satellites, and we had to do better than that. But remove the Soviet Union, and we tried to tell the world what to do—it doesn’t work. And it only got worse with the rise of the neocons.

“The French, for example, get terribly annoyed when Americans and conservative British tell them that France has to cut down on social security and work longer hours,” he continues. “The French know enough about America to know that there are aspects of American life that they don’t want—overwork, short vacations, and rather poor social and public services, for example.” Not long ago, during a taxi ride to Boston’s Logan Airport (Hoffmann was about to fly to Holland), the driver asked how the Dutch were doing. “They are doing fine,” Hoffmann replied. “They are at least as prosperous as we are, maybe even more so.” The driver said, “But that’s not possible! We are the most prosperous country in the world!”

With his dual citizenship, writing in both French and English (he sometimes translates himself), and with strong sympathies toward both nations, Hoffmann is ideally equipped to explain France to Americans and Americans to France. His full-year course, “Political Doctrines and Society: Modern France,” which he taught for more than three decades beginning in 1957 and into which, he has written, “I poured everything I knew and thought about France, and out of which came most of what I have written on her,” he calls the achievement of which he is most proud, because there was nothing like it. “I was, I am, French intellectually,” he wrote. “My sensibility is largely French—I like the frequent obliqueness, indirection, understatement and pudeur [modesty] of French feelings. But in my social being, there is something that rebels against the French harness, style of authority, and of human relations.”

Historical perspectives inform Hoffmann’s explanations of modern France. World War I, for example, was fought in France and the Low Countries—not in England or the United States. In the war, France lost 1.4 million soldiers out of a national population of 40 million; an equivalent loss for the United States today would be 10.5 million troops—nearly 3,000 times the current U.S. military death toll in Iraq. “France had a very, very rocky time after World War I,” Hoffmann explains. “Many came back mutilated, there was general exhaustion, and most people were turning pacifist because they didn’t want another war. In World War II they lost ‘only’ 600,000. But the period after World War II was one of extraordinary creativity in France; they came out of that war less exhausted and with a growing birth rate and much more vitality.”

That postwar vitality energized the young Hoffmann, who as a 16-year-old recharged his energies by spending the summer of 1945 lounging on the benches of the Bois de Boulogne, absorbed in the novels of Andr Malraux. (“If anybody ever gave me the impression of a genius, it was Malraux,” Hoffmann says, recalling a 1972 meeting he and his wife Inge [Schneier] Hoffmann had with the writer. “You cannot reproduce a conversation with Malraux; he started at 20,000 feet, there was no small talk. He was utterly charming, witty, sardonic.”) Hoffmann became a naturalized French citizen in 1947, enrolled in doctoral studies in law, and went to the Salzburg Seminar in American studies in the summer of 1950, deepening his fascination with the United States.

In 1951 he came to study in Harvard’s government department, receiving an A.M. in 1952. He then returned to France for army service (“sheer boredom”), and when he wrote to Harvard to say he wouldn’t mind returning, the department surprised him by offering, not the chance to write a Ph.D. thesis, but an instructorship. His “rather monstrous” law thesis, published in 1954, sufficed as a credential.

When he came to Cambridge to stay in 1955, Hoffmann decided, “This was a wonderful place. I felt I could live here and remain French. It was a cosmopolitan place in which one could function without anyone wondering where your passport was issued.” He smiles, adding, ”I am French, and a citizen of Harvard.”

Hoffmann is a professor in the grand classical sense, a man of wide learning rather than a discipline-bound specialist. “He’s a profoundly cultured man,” says Ellen Frost. New York Times columnist Thomas Friedman, who, as a visiting lecturer in the government department in 2000, taught a course on globalization with Hoffmann and Sandel, says, “What I like about Stanley’s writings in the New York Review of Books is that he doesn’t engage in these crazy numerical or quantitative analyses of international relations. You live it and breathe it when you listen to him, because it’s really textured by deep knowledge of history, philosophy, sociology—he weaves all the strands together.”

Albert Camus had a major influence on Hoffmann, who this spring gave a new course (in French) on the writer. “His existentialism is the philosophy to which I feel the closest,” he says. He met Camus only once, when the latter was giving a talk to American students in Paris. “He was irresistible,” Hoffmann recalls. “Very charming. He looked like a handsomer version of Humphrey Bogart. Camus’ influence on society and culture was a much greater one [than Sartre’s], because he was much more readable—he wrote unbelievably beautiful French.”

The myth of Sisyphus, which Camus used as a touchstone for an eponymous 1942 essay, also informs Hoffmann’s philosophy. “There are two main ideas I take from Camus,” he says. “One, that there is no such thing as linear progress: the rock has a tendency to roll back down the hill again, and nothing is ever finally accomplished. Second, one has to keep trying anyhow; that the rock will roll down again shouldn’t prevent you from trying to push it back up.” Hoffmann typically closed the last lecture of his course on ethics and international relations (which he first offered in 1980 with Michael Smith, and will give again with J. Bryan Hehir, Montgomery professor of practice of religion and public life, next spring) by reading the two final paragraphs of The Plague, where Camus explains that after the end of the plague, “the rats will return to the city.” The victories won for humanity are always provisional ones.

His mentor Raymond Aron declared that “Anyone who believes that all good things will come together at the same time is a fool,” Hoffmann says. “My quarrel with Thomas Friedman is that he believes that thanks to globalization, individual liberty, democracy, prosperity, and peace will all arrive together. That requires a breathtaking optimism or navet, and also explains his initial enthusiasm for the invasion of Iraq. Friedman is not an imperialist, but he does have this conviction that America has this formula for the world that will be good for everybody.”

Hoffmann finds the contemporary international situation grim and much of current U.S. foreign policy both benighted and disheartening. “One reason I haven’t been teaching international relations this year is I find it so discouraging, I can’t face it,” he confides. “If someone told me that after the end of the Cold War, one would hear about nothing but terrorism, suicide bombings, displaced people, and genocides, I would not have believed it.”

Twenty-seven students and auditors, ranging in age from undergraduates to some in their 60s and 70s, sit at their places in Sever this spring for French 190, Hoffmann’s course on Camus. In front of the room, their professor is eloquent, graceful, and gently humorous; when a student opens the window shades, he quotes Goethe’s dying words, “Mehr Licht!” [“More light!”] Hoffmann’s lectures “are finished works in themselves,” says Louise Richardson, noting that Harvard faculty often sit in the back, auditing the artful presentations. “How many international relations scholars will you find teaching Camus?” asks Thomas Friedman. “They don’t make them like Stanley anymore.”

Hoffmann once asked Richardson, who has studied the 1956 Suez crisis in depth, to suggest some relevant readings because he was preparing a lecture that dealt with it. “I recommended five books,” she recalls. “And he read all five!—even though the Suez crisis was only a small piece of the lecture. Stanley takes scholarship and teaching very seriously. He reads an extraordinary amount.”

In true European style, he is also happy to ask his students to do the same, and compiled impressively long reading lists for full-year courses like “War,” which had three lectures per week, plus a section. War and Peace could be the assigned text for just one of those lectures. When asked if that was unreasonable, and if an excerpt from Tolstoy’s magnum opus might not suffice, Hoffmann asked, “Which part of War and Peace summarizes the themes?”

Ellen Frost had Hoffmann for her junior tutorial in social studies. “He was brilliant, and because I was young, that was intimidating,” she recalls. “But he was also very caring. He saw through any kind of pretension, hypocrisy, or bluff, and has a deliciously wicked sense of humor, tinged with paradox. Humor permeates him.” Hoffmann once observed that, “What the classical economists called ‘harmony of interest through accumulation of goods,’ Rousseau summed up in one word: ‘greed.’” Discussing Woodrow Wilson’s Fourteen Points, he might casually quote Clemenceau to the effect that “Even God didn’t need 14 points.”

Michael Smith describes Hoffmann’s teaching style as “rigorous presentation of competing points of view at their most persuasive, followed by a devastating critique, followed by his own take on the issue. There are two ways of teaching: provide a suit straight off the rack, so to speak, or plant seeds and let them grow. Stanley plants seeds; he allows you to develop your own arguments.” Smith adds that “one of Stanley’s signal virtues as a teacher is that he treats everyone as an intellectual equal. You can be a freshman or a head of state and you’ll get exactly the same Stanley: he doesn’t dumb anything down and he doesn’t flatter you for the sake of your position. There’s not an ounce of condescension in him.” (Right after earning her doctorate, Frost wrote her mentor a long letter about her first job, working in the U.S. Senate. “Back came the loveliest handwritten letter,” she recalls. “It said, ‘Dear Ellen, Please call me Stanley, unless you want me to call you Dr. Frost.’”)

During the Harvard student protests in the spring of 1969, Hoffmann led teach-ins on Vietnam and became something of a hero to undergraduates. “Some of the students’ grievances were perfectly understandable, and the decision to call the police was an unbelievable mistake. [President Nathan] Pusey said that the confrontation had nothing to do with politics, that this was a problem of ‘manners.’ On the right, some conservatives in several departments were on a rampage. At the first faculty meeting after the University Hall occupation, [economic historian] Alexander Gerschenkron explained that the students were exactly like the Bolsheviks in Russia, and that there was only one thing you could do with such students: ‘Beat them! Beat them! Beat them!’”

At the same time, Hoffmann didn’t countenance the left-wing students’ ambition to shut down the University, and felt it was important “to prevent the ‘ultras’ [extremists] from taking over. I was really concerned with trying to keep it together,” he recalls. “Stanley is passionately committed to open debate and free intellectual exchange,” Frost explains. “To him, that is the soul of a university.” That, and of course, its students. “What mattered [in 1969] was that one listened to what the students had to say,” Hoffmann says, “because students were what the University was about.”

Hoffmann listens carefully to his own students, who frequently end as colleagues and friends. “I’ve been a teacher first, and a writer second,” he says, notwithstanding his 18 books. “I like writing, but it’s a lonely job and I am happier in front of a classroom than a blank page. I need the input and the stimulation that the students provide. They are fun. I am not ready to give up yet—or rather, I am ready, each time I am away from my students. But when I am with them, I want to go on forever.”

A traditional debate among international-relations scholars pits “realists,” who believe that national self-interests and power considerations ought to guide decisions, against “cosmopolitans,” who emphasize universal values like human rights over national self-interest. Hoffmann, a complex and subtle thinker, does not fit easily into either camp. “I’ve always considered Stanley a liberal realist,” says Sultan of Oman professor of international relations and former dean of the Kennedy School of Government Joseph Nye, a Hoffmann student. “He has always understood both dimensions.”

Like Camus, Hoffmann has a passion for human rights, broadly conceived, and a powerful ethical sense. Ellen Frost contrasts the pragmatism of the realist Henry Kissinger with Hoffmann’s cosmopolitanism. “Kissinger feels that the American public accepts foreign-policy initiatives only if they are tied to some ethical rationale,” she says. “Stanley has a different approach: he thinks foreign policy should be infused with universal ethical principles.” Smith notes that Hoffmann “was influential in bringing the study of norms and ethics to mainstream international relations. It had been marginalized.”

“As an academic, I have had one thread to guide me in my divagations: concern for world order,” Hoffmann writes. He defines world order as including how states arrange their relations to prevent a permanent state of war, and how they orient themselves in the postwar international system. That said, he is not a pacifist, and if he generally favors international cooperation, it is not so much for moral reasons as because, as Frost explains, “Things are more likely to work if you have other countries helping out.”

Though Hoffmann disagreed with his domestic policies, he feels that President George H.W. Bush did a “masterful” job managing the transition to the post-Cold War era. “Without gloating, he handled the Soviet breakup, the reunification of Germany, even the Gulf War very well,” Hoffmann says.

In his estimate, the greatest statesman of his lifetime was Charles de Gaulle. “There is no exact equivalent for the word ‘leadership’ in French,” Hoffmann says. “I recently reread de Gaulle’s speeches and marveled at the eloquence of his style, the pedagogical talent he had—he was the son of a schoolteacher. For the French, leadership means pedagogy: the capacity to explain the world, and to make people feel that the leadership takes them seriously. We haven’t had a real teacher since de Gaulle, and that has produced a funk in France. One component of leadership is making people feel that they are intelligent, that they understand. It’s something that has been missing in both France and America for a long time. People want to be enlightened. If you don’t do that, if it is all electoral tricks, or canned speeches, then there is going to be nothing but contempt and distrust of the people in power.”

Similarly, “In the old days, international relations was understood by average people, and today it is not,” Hoffmann declares. “Jargon has invaded everything and the relationship of theories to reality has faded. There are all these wonderful equations, but how are they affected by a real-world phenomenon like death? When I came to Harvard, American foreign policy was near the top of the hierarchy of subjects taught here. Today, there is no tenured government professor teaching American foreign policy. At present, the hierarchy of prestige values everything that is abstract and theoretical, and you cannot do that with foreign-policy studies. They have to be concrete and deal with concrete issues.”

Reality, with its complexities and paradoxes, continues to absorb him. He enjoys welcoming former French prime minister Dominique de Villepin to Harvard as much as he does teaching a freshman seminar on “Moral Choices in Literature and Politics.” The best word for Hoffmann’s thinking and writing might be “nuanced,” reflecting his deep reading of the facts, including those that seem to have escaped everyone else’s attention. His goal is always to understand, and, on a good day, perhaps exert a bit of influence as well, but never to reach fixed conclusions. In Hoffmann’s festschrift, the late Judith Shklar, former Cowles professor of government and Hoffmann’s close friend, summed up the pleasures of teaching and learning with him. Her essay tried, she said, to give an idea of “what it was like to have gone on a long intellectual journey with him that contemplates no arrival, but only the pleasures of the open road.”

Craig A. Lambert ’69, Ph.D. ’78, is deputy editor of this magazine.