Culminating her lifelong devotion to art collecting, connoisseurship, and scholarship—and a matching engagement with the University—Emily Rauh Pulitzer, A.M. '63, has given the Harvard Art Museum 31 important works of modern and contemporary art (one of the most significant such donations in the museum’s history) and a $45-million financial gift (the largest single donation in its history). (Download a PDF of Harvard Magazine’s 1988 full-color report on diverse works assembled by the Pulitzers, covering the Fogg’s fiftieth-anniversary exhibition of Modern Art from the Pulitzer Collection, including reproductions of a dozen works by Bonnard, Gris, Matisse, Modigliani, Picasso, Pollock, Rothko, and others.)

At the same time, the art museum disclosed previous gifts of 43 other modern and contemporary works, made between 1953 and 2005 by Emily Pulitzer and her late husband, Joseph Pulitzer Jr. '36, and by Mr. Pulitzer and his first wife, Louise Vauclain (who died in 1968), and of financial support that enabled the museum over time to purchase 92 additional works of art—thus accounting for a significant part of the modern and contemporary masterworks in the museum’s collections. The new gifts and announcement of the prior philanthropies come at a time of major physical renewal and programmatic extension of the art museum complex (the Fogg, Busch-Reisinger, and Sackler museums), and shortly before the expected release of the report of President Drew Faust’s task force charged with exploring the expansion of the arts, broadly defined, at Harvard, and their integration into the University’s academic and extracurricular life.

"The Harvard Art Museum's distinguished collections and dedication to teaching and research in the arts have had a significant impact on the field, on scholarship, and on my own life," said Mrs. Pulitzer in the University’s news release. "Both Joe and I have supported the art museum over the years in recognition of Harvard's unparalleled role in the development of professionals in the arts worldwide and because of our belief that the arts are a cornerstone in learning and education in all fields. My gift is also a way of thanking Harvard for the enrichment of my life and the defining role that art has played for me. The Harvard Art Museum's new project will expand the ways that art advances education even further and I am very proud to support the museum as it moves forward."

Faust added, "I am especially grateful for this remarkable gift because it is the continuation of a lifetime of giving of art, financial support, and time to the art museum and Harvard by Emmy and Joe. The arts are central to the academic life of Harvard University. Emmy's generosity will help ensure that they play an even more robust role on campus and in the lives of all our students, whether they are studying the arts, economics, law, medicine, physics, or other disciplines." In a subsequent conversation, Faust amplified her enthusiasm for “an enormously important gift in so many dimensions”—from physical renovation of the Fogg to the “injection of energy and possibility” that “reinforces everything we’re trying to do” in mobilizing University commitment to the arts.

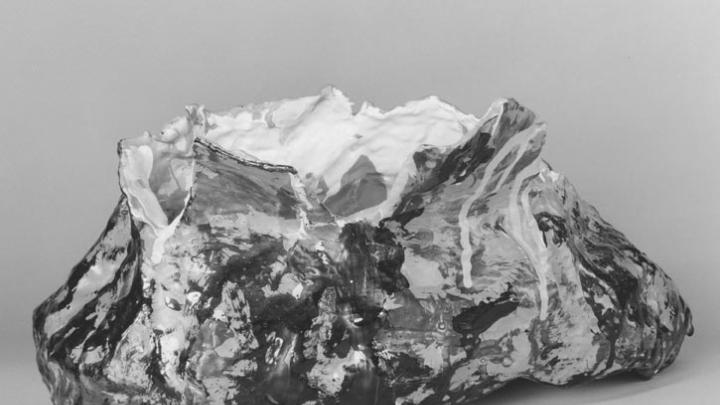

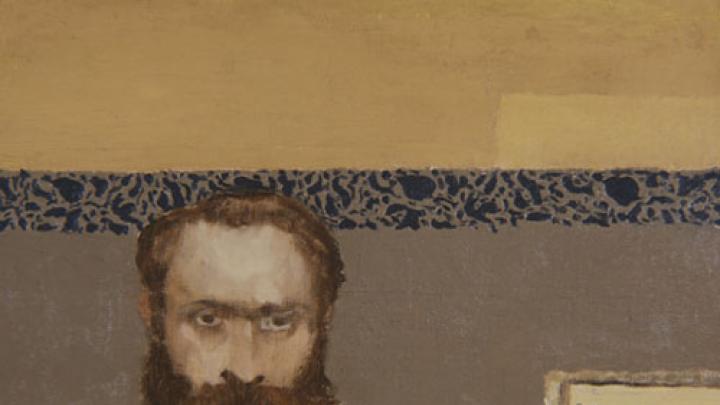

• Works of art donated. According to the University news release, the new Pulitzer gift includes modern paintings and sculptures by Brancusi, Derain, Giacometti, Lipchitz, Miro, Modigliani, Picasso, Rosso, and Vuillard, plus major contemporary works by di Suvero, Heizer, Judd, Lichtenstein, Nauman, Newman, Oldenburg, Serra, Shapiro, and Tuttle (for complete list, view pdf). The previous gifts—made between 1953 and 2005 and being acknowledged now—included paintings by Braque, Cezanne, Miro, Monet, Picasso, and Stella, and works on paper by Cezanne, Degas, and Delaunay. The 92 other works of art purchased by the museum with financial assistance from the Pulitzers included paintings by Baselitz, Braque, and Mondrian, works on paper by Ellsworth Kelly, LeWitt, Marden, Serra, David Smith, and Twombly, and a collection of Indian paintings on paper. Faust noted, in the interview, that the addition of modern and contemporary masterpieces was especially valuable because such works are “a focus of enthusiasm and interest for our students,” but have been underrepresented in Harvard’s collections.

• Financial support for Fogg renovation. The financial gift will be applied to the Fogg renovation. (This diagram and narrative provide some sense of the scale of the project, being designed by Renzo Piano—with new entrances and interior circulation, reoriented galleries, glass atriums, and internal study centers for academic use of the collections). Faust observed that the building program is not merely a physical project; rather, its mix of spaces aims to augment curricular use of the museums, as well as scholarly research. In a separate conversation, Emily Rauh Pulitzer praised the way Harvard Art Museums director Thomas Lentz “picked up on the extraordinary quality of the Mongan Center,” where the drawing collections are made accessible for teaching and study, “as a very special art-viewing experience.” A feature of the new Fogg design that has “great appeal” is its mixture of study rooms, seminar spaces, galleries for changing exhibitions tied to courses, and galleries for more permanent exhibitions. This variety of viewing experiences, she said, “is so important. One of the problems I see as museums get bigger is that it’s deadening,” as visitors work their weary way through endless rooms hung with painting after painting. In contrast, she said of the Fogg plan, “This is going to provide really stimulating opportunities for looking and learning.”

• Lifetimes immersed in art. Explaining the evolution of her interests, Pulitzer recalled growing up “in the first modern house in Cincinnati, a Bauhaus-type house” decorated with some paintings her parents had collected. Encountering a work by, say, Leger or Ben Nicholson—modern, to be sure, but nothing particularly far-out—guests asked, “Why do you call that art—what’s that all about?” Pulitzer remembered trying to respond to such questions. She was also in the company of two aunts who began Cincinnati’s Modern Art Society (now the Contemporary Arts Center). So stimulated, she determined to study the subject at Bryn Mawr College, and found courses on art history and twentieth-century architecture “very important.” After she graduated in 1955, Pulitzer pursued her interest the next year at the Ecole du Louvre. In 1956 and 1957, she interned on the staff of the Cincinnati Art Museum, before coming to Harvard as assistant curator of drawings at the Fogg, a position she held from 1957 to 1964, in which capacity she worked with renowned curator Agnes Mongan. In fact, Pulitzer said with a laugh, she got the position through the “old girls’ network” through fellow alumna Mongan. That work, she said, “changed my life. It was an amazing experience,” with extraordinary colleagues and fellow graduate students. She also served as assistant to John Coolidge, the director, in 1962-1963 (”a great mentor”) and completed her A.M. that same year. She then served as curator at the St. Louis Art Museum from 1964 to 1973 (initially the only curator, and then one among a growing staff as the museum was rebuilt from “a shambles”), and married Joseph Pulitzer Jr. in the latter year.

Joseph Pulitzer Jr., as narrated in Judith Parker’s 1988 Harvard Magazine article, was smitten by art even before arriving at Harvard College, and made the subject a major part of his studies (his senior thesis was on Picasso, Parker reported). By his senior year, he was consulting with Paul J. Sachs—a legendary connoisseur and associate director of the Fogg Art Museum—about the advisability of purchasing a Modigliani portrait. From his graduation in 1936, Pulitzer’s involvement in the family’s St. Louis-based publishing business, in art collecting—first with Louise Vauclain, whom he married in 1939, and then with Emily Rauh—and in Harvard’s museums and art department appear to have proceeded with equal passion. Parts of the collection were exhibited at the University in 1957 and in 1971, before the major 1988 show. Parker detailed the development of Pulitzer’s “steadily widening knowledge and the intensification of his tastes,” resulting in a body of works considered classic in the traditional sense of that word. “I’ve always bought things that were meaningful to me, hoping there would be a certain character, coherence, or personality to the collection,” he told Parker.

Following his first wife’s death in 1968, Pulitzer and Emily Rauh married in 1973 (they had once met at the Fogg a decade earlier, Parker reported), forming a partnership that was apparently enriched and deepened by their mutual tastes and interests in art. More than anyone he had met since Paul Sachs, he told Parker, Rauh “aided and helped and encouraged me” and “opened my eyes to art immediately being produced, whereas my tendency has been to wait until the dust settles.” In turn, she spoke of “the quality and the passion and the continued commitment” of his collecting “over a very long period of time.” That collecting extended to outdoor sculpture (by Judd, Serra, di Suvero, and others) displayed at their summer estate in Ladue, Missouri, complementing earlier works by Rodin, Arp, and others, Parker reported. During her visit, Joseph Pulitzer told Parker, “A significant work of art reveals a truth unknown up until then, intensifies the perception of the human condition, or provides a sign or symbol for a deeper comprehension of contemporary experience.” (Modern Painting, Drawing, and Sculpture, a four-volume catalog of the Pulitzer Collection, was published from 1958 to 1988; volume four was prepared by art scholar Angelica Zander Rudenstine, whose husband, Neil, in yet another University connection, became Harvard’s president in 1991.)

Beyond the collecting, Emily Rauh Pulitzer has been involved in the front ranks of public art leadership in many capacities around the country. She has been a member of the Museum of Modern Art’s painting and sculpture committee since 1985 (and vice chair since 1996), and a MOMA trustee since 1994 (thus sharing an important institutional affiliation with Joseph Pulitzer’s classmate, David Rockefeller '36, G '37, LL.D. '69—whose own life of engagement with art and strong support for the Harvard Art Museum were marked by a leading philanthropic gift to the University last spring). She has devoted more than a quarter-century of service to the board of directors of the Contemporary Art Museum St. Louis. And most significantly, she founded, and now chairs, the Pulitzer Foundation for the Arts, which opened an acclaimed arts-exhibition space in St. Louis in October 2001, designed by the Japanese architect Tadao Ando—his first freestanding commission in the United States. She commissioned site-specific works by Richard Serra and Ellsworth Kelly for the opening (in 1982-1983, Emily Pulitzer was co-curator of the first major retrospective of Kelly’s sculpture, at the Whitney Museum of Art and the St. Louis Art Museum, and was coauthor of the exhibition catalog, Ellsworth Kelly: Sculpture, with Patterson Sims), but it is explicitly not tied to art works collected by the Pulitzers. The Foundation maintains on line an interview with Pulitzer about the genesis and goals of the project. (A recent Ando project, the Stone Hill Center at the Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute, in Williamstown, Massachusetts, which opened this past June, also contains contemporary exhibition space and facilities for the Clark’s acclaimed conservation laboratory—making it part of a northwestern Massachusetts locus for art museumship and scholarship, similar to Harvard’s three associated art museums and the Straus Center for Conservation in Cambridge.)

Demonstrating her appetite for exploration, Pulitzer said that the foundation was in the process of installing an exhibition of drawings and Old Master paintings from the Fogg and the St. Louis Art Museum. It promises startling juxtapositions and fresh ways of seeing such works in the very modern Ando building.

(Ideal (Dis-)Placements: Old Masters at the Pulitzer opens Friday, October 24.) “I hope for many more connections among the three institutions,” she said.

In an interview, Neil Rudenstine said of the Pulitzers that "individually and together they were often daring, always passionate collectors, who cared deeply about the art with which they lived. As a young man, barely out of college, Joe bought Matisse's 1908 Bathers with Turtle— a mysterious masterpiece still challenging today. In 1970, he had the courage to commission Richard Serra's first site-specific sculpture for his summer house, and then continued—with Emmy—to buy Serra's work.” (A Serra sculpture is among the works in the new gift of art to Harvard.) Rudenstine noted Emily Pulitzer’s leading role in developing appreciation of Ellsworth Kelly, saying that the artist “was a very early commitment of Emmy's, and together she and Joe acquired wonderful examples of his work year after year.” Similarly, “Commissioning Ando to design the Pulitzer Foundation building after Joe died was another pioneering step on Emmy's part—and the result is a stunning building, an absolute gem,” and one with wider impact: “It has become an important element in strengthening a nascent arts district in St.Louis, to which Joe and Emmy always had a deep commitment.” That commitment was mirrored by their obvious engagement with the University: “Both Joe and Emmy cared deeply about Harvard,” Rudenstine said, “and this gift represents an extraordinary culmination of their lifetime generosity and belief in the power both of art and of education."

• Involvement with art at Harvard. Beyond their academic work and collection exhibitions at Harvard, Joseph Pulitzer Jr. was and Emily Rauh Pulitzer has been engaged with the University’s arts programs and facilities—and increasingly, with the senior administration of the University itself—for decades. According to the news release, Joseph Pulitzer served on the visiting committee to the fine arts department from 1949 to 1971 and from 1976 to 1982 (as chair during the latter period). He was a member of the visiting committee to the art museum from 1971 to 1993, serving as vice chair from 1976 to 1983. And he was a member of the University’s Board of Overseers from 1976 to 1982. In 1939, the news release notes, he pledged a $6,000 gift, over three years, for a postgraduate fellowship to study art abroad. In 1958, again anonymously, he established a fund for the acquisition of modern art. At his fortieth reunion, in 1976, he established a named endowment to support research travel for undergraduates concentrating in art history. He also endowed a professorship of modern art in the Faculty of Arts and Sciences (activated with the appointment of Yve-Alain Bois in 1991).

Joseph Pulitzer was a restrained contributor to his College class reports, but he did write at length, and revealingly, about his interest in art for his twenty-fifth reunion report, in 1961: “At Harvard I developed a latent or inherited interest in art which has been a source of profound interest and pleasure. As a reflection of the spirit of its time, modern art has particularly held my interest. My hobby is collecting drawing, painting, and sculpture, and while my correspondence has grown fat and my pocketbook lean, I have enjoyed the friendship of artists, critics, collectors, dealers, teachers, and museum men. Often their devotion to their calling has set examples of inspired professional commitment or involvement, which could not fail as a stimulus to one who happily chose journalism as a profession, but who gravitated toward art as an avocation. In 1957 the Fogg museum published two volumes entitled Modern Painting, Drawing and Sculpture: Collected by Louise and Joseph Pulitzer Jr., to which I was an incidental contributor and, I trust, a helpful adviser and part-time editor.” (It is this series which has since been extended to four volumes.)

Emily Rauh Pulitzer joined the visiting committee to the art museum in 1990, and became its chair in 2004; she has also served on and chaired the museum’s collections committee. She was elected a Harvard University Overseer in 2006, and became a member of the President’s Advisory Committee on the Allston Initiative in 2005; as planning for campus development in Allston proceeds, and as the president’s arts task force reports, it is expected that provision for extensive cultural facilities may be made there—ranging from museum space (perhaps particularly with large galleries for monumental contemporary works) to various performance venues.

In the interview, she said that there was “absolutely” a need for Harvard to pursue museum space beyond the Quincy Street complex. Reflecting upon earlier plans for a new museum on the Charles River at Western Avenue, or in Allston, she said, “It’s been very difficult and very painful to have those two earlier projects canceled” after much hard work. But given the huge effort involved in the Fogg renovation, she said, “I think it’s really fortunate in a way, because what [ultimately] comes in Allston will be so much better”—in the wake of Harvard’s forthcoming revision of the Allston plans and the pending task-force report on the arts at Harvard in general. New art museum spaces, a new plan for the Peabody Museum, and new performing-arts facilities as yet unimagined are all part of the Allston possibilities she envisions.

In choosing to donate a significant part of her collection to Harvard, and supporting the University art museum financially, as a center for art scholarship, teaching, and conservation, Emily Rauh Pulitzer has made a major statement about her own life of learning and of deep devotion to visual experience. She has, at the same time, left her own mark, and her family’s, on a broad range of arts institutions in St. Louis—her husband’s hometown and now, for many years, the center of her own life and civic engagement. In balancing those centers of her universe, Pulitzer has apparently put into practice an observation she made about the Pulitzer Foundation for the Arts—which is explicitly not focused on her personal collection—in a 2005 interview: “As a collector and a curator by profession, it seemed clear to me from the beginning that the Foundation should not own a collection, since this would have been limiting to the viewer's experience, as well as to curatorial possibilities. I am very interested in exploring curatorial possibilities and challenges.” In a comment that could as well apply to Harvard today, she continued, “Experience—mainly in the domain of collections turned into museums—has shown that the mission has either been defined too narrowly or too broadly, often resulting in great difficulties for these institutions to remain vital. I strongly hope that the Pulitzer will remain a place of possibilities with whatever occurs being of the highest quality.”

For The New York Times’s coverage of the gift, visit here.