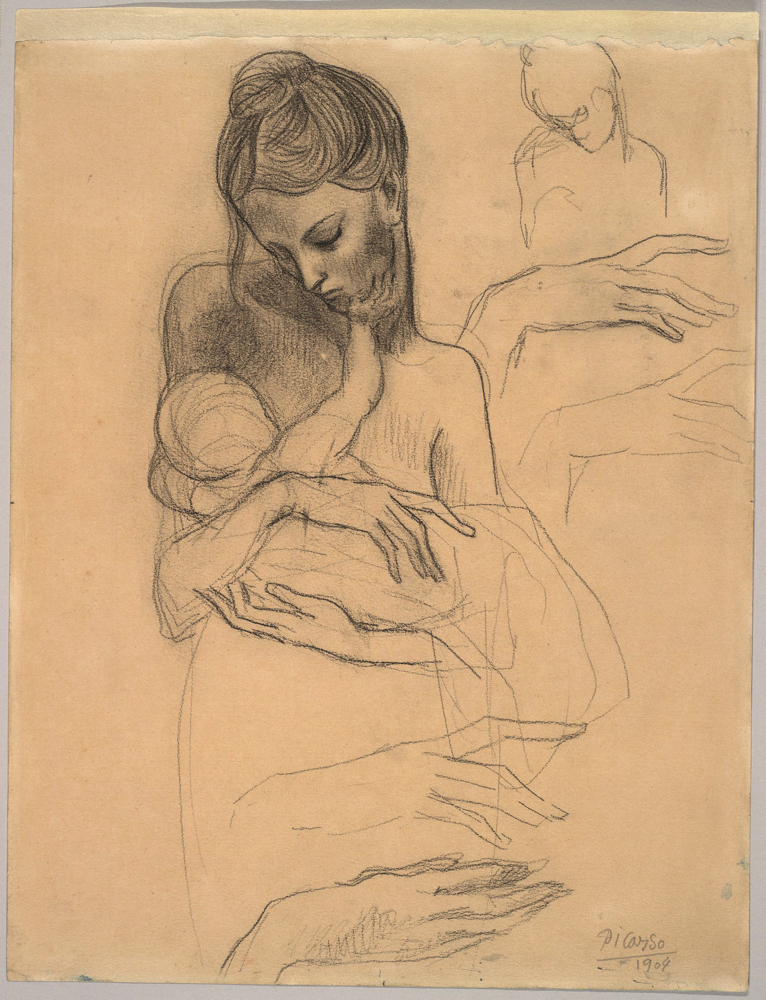

In 1903, Pablo Picasso sketched a woman cradling a child, her neck twisted downward toward the little figure, whose arm reaches up to cup her cheek. Beside them he drew studies of the woman’s hand, trying to capture the way her fingers curled around the baby’s body. The woman was inspired, in part, by his then-lover Fernande Olivier—the baby imagined, as the couple had no children.

A Mother and Child and Four Studies of Her Right Hand, 1904; verso: Self-Portrait Standing, 1903 | Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum, Bequest of Meta and Paul J. Sachs; © Estate of Pablo Picasso / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

If viewers could see through the paper, they’d glimpse a stark, unfinished male figure on the other side, chest and legs devoid of detailing: a nude self-portrait. The two sides of the paper represented Picasso’s opposing desires between “artistic productivity and bearing children,” says Suzanne Blier, whose art and architecture history course “World Fairs” complements an installation of Picasso works at the Harvard Art Museums on display until May 5, “Picasso: War, Combat, and Revolution.” When Picasso was 13, his sister Conchita fell ill with diphtheria; he told God that, if she survived, he’d give up his art. From the time he made that promise—and especially after his sister’s death—Picasso believed in a tension between art and life, an incompatibility between these two types of creation.

One might wonder if there is really a connection between the two sides of the paper. After all, only one—that depicting the mother and child—is visible in the gallery (though the self-portrait is recreated below the sketch). But imagining what is on the other side is in line with Picasso’s artistic project: throughout his career, he was concerned with trying “to see through things, to see into the interior,” says Blier, Clowes professor of fine arts and professor of African and African American studies, “to understand individuals not by what we see on the surface, but by discerning the core elements within them.”

That urge is evident in many of the other works in the exhibit, which are united by an exploration of war, broadly interpreted. Picasso’s famous 1937 painting Guernica—which is not included in this installation, but was lent to Harvard’s Fogg Art Museum to be exhibited in 1941 and 1942—depicts the Fascist-era bombing of Guernica in 1937 through violent specificity: a dead child, a dismembered soldier. Some pieces in Harvard’s exhibit have a similarly explicitly political bent, including 1937 political cartoons that critically depict the Spanish fascist leader Francisco Franco, “The Dream and Lie of Franco.”

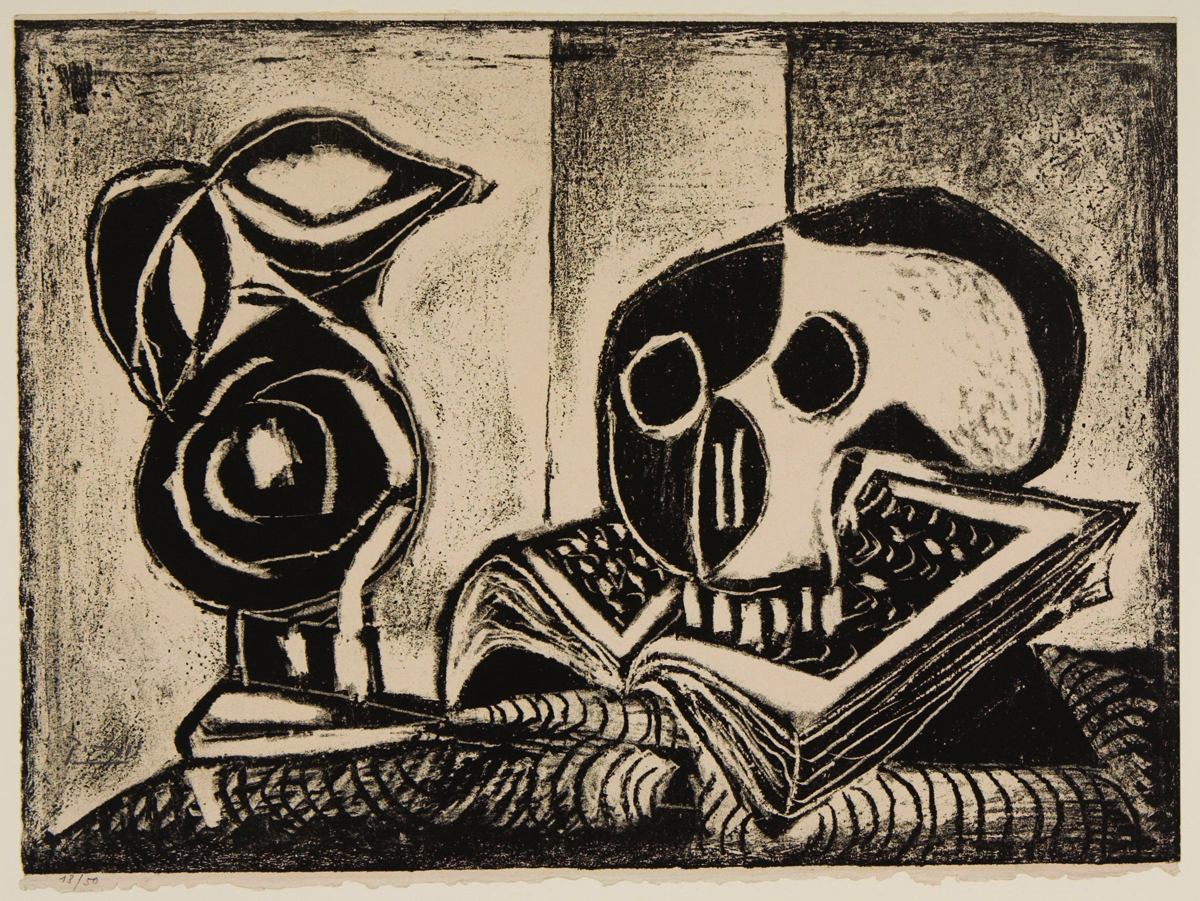

| Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum, Gray Collection of Engravings Fund; © Estate of Pablo Picasso / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Other works in the exhibit deal with war, combat, and revolution more obliquely. A print from 1953 depicts a goat skull on a table in black and white, the skull serving “as a memory image of death,” Blier says. A 1949 lithograph depicts a lobster, but as if taken by an X-ray: Picasso paints the animal’s skeleton, another instance of his looking beneath the surface.

Picasso’s works about women and love—including the sketch of the mother and child—also provide an indirect look into his explorations of conquest and violence. Hanging next to the mother and child is a handwritten card and a sketch of a nude woman Picasso made for a friend, playing with the idea that “by drawing someone else’s wife or girlfriend, you are in a way taking them,” Blier says. “So there was that kind of element in play, as well—conquest, combat, competition.” Last year marked 50 years since the artist’s death, with special exhibits around the globe for the anniversary—prompting a resurgence of criticism of Picasso’s mistreatment of his wives and mistresses. These works provide an opportunity to scrutinize how he portrayed women, both engaging with and challenging the notions of violence and conquest often associated with their depictions.

The works on display at the Harvard Art Museums span decades of Picasso’s life. Scholars of Picasso tend to focus on particular periods in his long career, Blier says; one benefit of this exhibit is that it displays works from different eras beside each other, so that visitors can see the similarities between them. The 1911 “Man with Pipe” fragments an image and displays it from multiple vantage points, “getting us to rethink how objectivity, how looking can be transformed by the ways that one is shaping things,” Blier says. In doing so, Picasso is “countering a whole longer history of European art.” The 1907 “Standing Nude Woman” appears, on its surface, quite different: it’s a straightforward depiction of a woman’s form. But in the context of Picasso’s other works, the red watercolor along the black ink of the woman’s outline becomes reminiscent of the blood beneath the woman’s skin, another attempt to see two perspectives—her inside and her outside—at once.

“The diversity of Picasso’s art is extraordinary, and I had the luxury to cross beyond those different periods,” Blier says. This allows viewers to see how, throughout his career, “he looked within things, gave expression to those various elements that help conceptualize the whole.”