In playwright Bess Wohl’s work—sweet and sharp and sad, and often darkly funny—something important is usually missing. In American Hero, it is the owner of a new sandwich franchise who mysteriously disappears, leaving his employees to drift between existential hope and despair. In Make Believe, the void left by their absent parents causes four young siblings, latchkey kids of the 1980s, to dream up fantasy worlds together in the attic of their home.

“There seems to always be some authority figure who should be there and is not,” says Wohl ’96. “Somebody who should be in charge but is absent, or inaccessible.” That’s true also of her best-known work, 2015’s Small Mouth Sounds, in which six strangers in search of inner peace find their way to a silent retreat deep in the woods. With a running time of 100 minutes, Small Mouth Sounds contains very little dialogue, and what there is belongs mostly to the retreat’s unseen guru, whose only presence is as a disembodied voice that grows increasingly loopy and unhinged. The New York Times named it “one of the year’s top plays” (“intrepid writing,” critic Charles Isherwood wrote), and this January, SpeakEasy Stage in Boston will mount a new production. “There’s a certain freedom of expression” in a play mostly without words, says the director, M. Bevin O’Gara. “I think this play makes the audience listen harder, by which I actually mean observe….By stripping away the language, Bess makes us more open and attuned to details.”

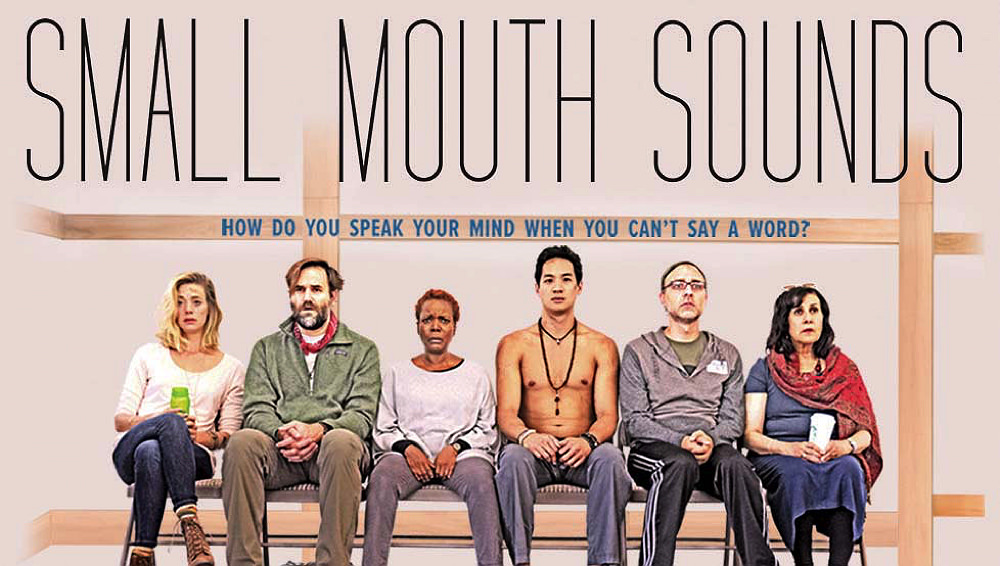

Poster for Small Mouth Sounds, listed as one of the best plays of 2015

Wohl never expected to write a play—she’d planned to become an actor. Growing up in Brooklyn gave her an early introduction to the theater. At three or four years old, she went with her grandmother to see the famous production of Peter Pan with Sandy Duncan in the title role. It left a deep impression. When Duncan flew out over the audience at the end of the play, “I was completely blown away....I didn’t know you could do anything like that.” Wohl wrote a fan letter to Duncan, who wrote back, enclosing a photo of herself as a flapper in a beaded headdress. “I have that picture framed to this day,” Wohl says. “As an actor, I always put Sandy up in my dressing room.”

An English concentrator, Wohl joined the Harvard-Radcliffe Dramatic Club and acted in several plays—appearing onstage as a television reporter, a sappy lover, one half of a married couple from Utah—and enrolled in Marjorie Garber’s two-semester course on Shakespeare. Garber, the Kenan professor of English and visual and environmental studies, “really instilled in me this idea that the theater can help you live your life,” Wohl says: “that the things you encounter in plays can become almost like a manual.”

After college, Wohl returned to New York, where her life filled with acting and auditioning. “I would do any reading for anything I could find,” she says. At the same time, she kept applying to the Yale Drama School’s M.F.A. program in acting. On the third try, she got in. It was in New Haven, while training to be an actor, that she became a playwright. “Yale has a student-run experimental performance space called Cabaret,” she explains, “and you can do anything you want there. You can work outside of your discipline.”

She came up with an idea for a play: a mock “talkback”—a post-show discussion, in which the director and cast members come onto the stage for an informal conversation with the audience. Her piece, Cats Talk Back, centered around five cast members from the Andrew Lloyd Webber musical Cats, and it was a riot. “A comedy, obviously—and a really strange play.” There were plants in the audience asking questions, and the cast performed a supposed “lost” number in which the cats maul a small child to death. Wohl and her cast took the play to the New York City International Fringe Festival, where it won best overall production. “To this day, it’s maybe my favorite thing I’ve ever done,” she says. “It really unlocked something in me. I remember vividly being in the Cabaret, sitting in the audience and watching people on stage perform these words that I had written. And I just felt this click, like, ‘This is something I could actually do.’”

After Yale, Wohl kept acting and writing simultaneously. She wrote a play about a young woman recovering from eight medicated years in a mental institution, and another about a young man trying, with professional help, to get into Harvard (“It’s really about the meritocracy and where it succeeds and where it fails”). She found small parts in films and television shows, and briefly moved to Los Angeles. But as her writing picked up speed, it became too hard to juggle both. She chose writing.

But acting still strongly influences her work. “So many things I learned have been helpful,” she says, “like the experience of thinking about character from the inside out, and having a sense, almost on a cellular level, of whether something is playable or not.”

Wohl’s new play, Continuity, debuting this spring at the Manhattan Theatre Club, is a dark comedy following a film crew in New Mexico through six takes of a single scene in a high-budget thriller about climate change. As usual, a figure of authority is missing. “There’s a sense of, ‘Is anybody out there?’” she says. “ “‘What’s going to happen to us?’ We’re sort of stranded on this planet and nobody is taking care of us in the way we had hoped.”

It took eight years and several drafts to write the play—for a long time she struggled with how to bring the subject to the page in a way that felt compelling. “So much of climate change is a failure of narrative,” she says. “When you talk to scientists, they say, ‘We haven’t found a narrative that connects with people enough.’ That’s what a writer is trying to do as well.” But as with other eternal questions concerning mortality and how to cope with it, theater is the right vehicle, she says. “Because plays themselves are so temporary. And the moment we have with them is so fleeting, and it never comes back. That’s what’s so exciting and precious about them to me. There’s something very resonant about looking at how temporary and fragile everything is in the context of this made thing that is here and then gone.”