On a sunny day in Oakland, California, more than a hundred kids at Laurel Elementary School spill outside for recess. They race across the blacktop, screeching and laughing, to jungle gyms, the basketball court, and a LEGO Lair. Others grab hula hoops, as two first-graders struggle to roll out a soccer net.

“Isn’t it awesome!” says Jill Vialet ’86 (’87), founder and CEO of Playworks, a nonprofit that partners with schools to promote exercise and social and emotional health through recess. Many American schools now don’t have recess, or take it away as a punishment, she explains. “But—you hear the kids? They need to be running around outside, screaming. And there’s chaos—but it’s a nice, positive chaos.”

A multisport athlete and two-time national club-rugby champion, Vialet founded Playworks’ precursor, Sports4Kids, in 1996. She’s since scaled up the model, supported by more than $32 million in grants from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and a 2006 Ashoka fellowship. With nearly 700 employees in 23 offices around the country, Playworks expects to reach 1.25 million children at 2,500 elementary schools this year—the majority from low-income families and neighborhoods. Awareness of its programming, Vialet says, is largely through word-of-mouth; Playworks contracts with individual schools as well as districts. Services range from on-site, full-time “play coaches,” to staff trainings, to consultations; Playworks defrays poorer districts’ program costs through fundraising.

As of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation’s 2010 report “The State of Play,” perhaps 40 percent of school districts had cut or reduced recess within the prior decade—despite many educators’ assertion that it positively affects academic achievement and social and emotional development. Constrained budgets, and pressures to teach to standardized tests, are partly to blame, and recess is easy to curtail, especially if it’s a locus of conflicts, as happens at many schools.

“To ask public-school teachers to create more time for free play is challenging,” Vialet continues. “American schools are being held accountable to a fairly narrow set of standards, and operating in a litigious world, and under-resourced, while being asked to solve and address some of our major social ills—it’s a total set-up.” Even though her sense is that “recess has been making a steady comeback,” in recent years, it typically lasts only 15 to 30 minutes; the American Academy of Pediatrics recommends a daily minimum of an hour of exercise. Shorter recesses can be ample, Vialet says—if they are strategically organized, with quick transitions, equipment and play zones in place, a repertoire of familiar games, and a capable “play coach.”

At Laurel Elementary, Playworks program coordinator Tayla Muise leads all the recesses, striking that sweet spot between structured and free play that Vialet (pronounced “violet”) enjoyed while growing up in the relatively leafy Cleveland Park section of Washington, D.C. But while she played outside with peers every day, she finds that many students now don’t, regardless of socioeconomic status. Whether that’s because of digital devices, parental fear of “stranger danger,” or objectively unsafe neighborhoods, they lack “the breadth of knowledge about how to play or start games,” she says—and especially how to keep them going after a disagreement.

Playworks’ “games library” includes dodge ball, four square, and freeze tag, Silly Fox and Sneaky Statue; coaches teach them to classes individually, and then post the rules on the playground. And while coaches may participate in a game, they also step back and let kids direct the play. “It’s not helicopter-parenting,” Vialet is quick to say. “It’s more like a camp counselor, or the older kids in the neighborhood, watching out.”

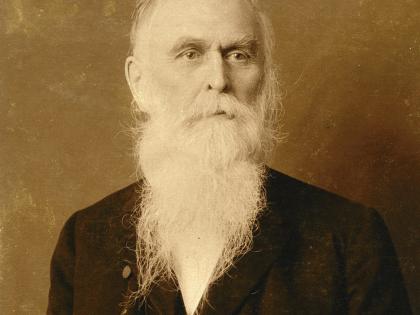

Vialet aims to right-size play and recess in children’s lives.

Photograph by Eric Kayne

One motley group of Laurel second-graders, for example, has been hooked on a hula-hoop version of Ro Sham Bo Relay for two weeks; teams have already lined up at opposite ends of 10 or so overlapping hula hoops. One player from each side hops as fast as she can through the hoops toward her opponent; when they meet, a quick round of rock-paper-scissors determines who advances. The fast-paced play develops hand-eye coordination, balance, and gross-motor skills (a lot of the kids are still learning to hop), along with the concept of boundaries, collective effort, and fair play. “They don’t really seem to keep score,” she notes, “or they’ll do it, and then forget what the score is.”

“I’m out!” one girl squeals happily, throwing her hands in the air and trotting back to her teammates, who are cheering on the next girl in line. “Delight is in short supply in the world,” says a laughing Vialet, who gives one player a hefty high five. “And for a lot of kids, the educational system is not a big source of delight.”

Vialet is not alone in affirming play’s substantive life lessons. “Inclusion, conflict-resolution, taking turns, decision-making, self-regulation, self-awareness, collaboration, empathy,” she says. “All the skills required for people to engage in civil society are things you learn in play.” Studies of Playworks’ impact point to reduced incidents of bullying and playground fights, and increased student classroom engagement. This year, a RAND Corporation report named it one of only seven elementary-school interventions designed to promote social and emotional learning skills (SELs, in education-policy circles) that meet the “highest criteria for evidence of impact under the Every Student Succeeds Act.”

“Usually academics think about levels of SELs being taught didactically in the classroom by a trained teacher delivering content to children,” Vialet explains; Playworks instead creates space and opportunities through which children more implicitly absorb that material through physical, social, and experiential modes. Role models like Muise, a soccer athlete, Mills College graduate, and former foster-care child, help. “I fundamentally think that it’s about ‘norming,’” Vialet adds. “It’s experiential education where you have grownups creating expectations” and showing kids how to behave—“they want to be like Coach Tayla because she’s active, and nice, and she likes everybody.”

Vialet loved recess, and was “insanely competitive” when she took up serious sports—field hockey and basketball and running track and cross-country—during high school in Chevy Chase, Maryland. The day she won the state championship, she came home and told her parents—John Vialet ’59 and Joyce [Cole] Vialet ’59, M.A.T. ’60—“and my mother said, and I quote, ‘That’s nice, dear, set the table.’” Vialet laughs again at how her opera- and art-oriented parents took it in stride. “I think that’s part of why I did sports, too—it was my own thing; I did it because I wanted to. I inherited some of my parents’ kind of benign-neglect parenting. I think it’s totally healthy.”

At Harvard, she played soccer, basketball, and rowed novice crew, but quickly fell in love with rugby, an emerging Radcliffe club sport. She liked the autonomous structure, and the “sort of ‘us against the world’ quality—these young women playing this gonzo sport, running around knocking people down.” (She later played for the Berkeley All-Blues, winning the National Club Championships twice, and toured Europe with the All-Stars team in 1992.)

Perhaps her exuberant resourcefulness led Wayne Meisel ’82 to tap her to work for Harvard’s House and Neighborhood Development Program (HAND), which he founded as an alternative to the Phillips Brooks House Association. Again, Vialet was drawn to HAND’s self-starting, integrated quality: the undergraduate Houses created their own projects and alliances with Boston and Cambridge communities. “It’s an interesting directional question—how do you see service?” she notes. “Is it something you go somewhere else and do? Or is it something that’s part of the fabric of your life?”

She took off junior year to travel in India, Nepal, and Japan, and then spent the summer of 1986 in South Africa working on her senior thesis: “a good Marxist, feminist tract on the economics and politics of female reproductive healthcare in South Africa.” Once back in Cambridge, she wrapped up coursework for her special concentration (a combination of social studies, women’s studies, and medical sociology), earned a teaching credential through a Harvard partnership with Cambridge Rindge and Latin School, all while also leading HAND, and graduated in 1987. Those years of liberal-arts exploration, and subsequent time spent in Alaska and Mexico, showed her that “there are so many unadvertised paths,” she says. “So, it all had ‘no apparent purpose’”—the dictionary definition of play—“and yet it really was ultimately singularly important in my finding my own purpose.”

Because the Bay Area promised more adventure than moving back home (and she could stay with her College roommate’s parents), Vialet landed in Berkeley after graduation. Then she began showing up at a progressive asset-management company “every day at 7 a.m., and kept asking, ‘Is there anything I can do?’”—figuring she’d build on her divestiture efforts at Harvard—until she was offered a job. Within 10 months there, she learned that financial-services weren’t for her, but maybe an idea and business plan she’d developed, to make art a fundamental part of every child’s daily life, might work.

That became the Museum of Children’s Arts, in Oakland, which she founded in 1991 and led for a decade. While there, she met with a principal concerned about three boys whose behavior on the playground was causing trouble and contributing to their self-images as “bad kids.” She asked Vialet for help. It struck Vialet then that thoughtfully planned play, like art, had potential benefits, and that recess, if “tweaked,” would have a huge impact on entire school systems.

These days, Playworks is still expanding, with Vialet’s partner, long-time nonprofit leader and activist Elizabeth Cushing, as its president, primarily in charge of operations. That frees Vialet to focus on “vision, fundraising, and having big ideas.” During a 2016-17 fellowship at Stanford’s Hasso Plattner Institute of Design, she forged a new nonprofit, Substantial. “At any moment, 10 percent of classrooms are led by substitute teachers,” she asserts, “so kids spend a full year of their K-12 education, and schools spend $4 billion a year, on subs, and 90 percent of districts offer four hours or less in training.” A digital platform to help teachers better communicate with subs about classroom curriculum, workflow, and assignments is in process. She’s also busy building a for-profit Playworks division, Workswell, that applies the games and play model to adults in the business sector.

Vialet works hard—but sometimes plays harder. “In the nonprofit community, people do this martyr thing and work these ridiculous hundreds of thousands of hours,” she says. “People are always surprised that I actually put in about 40 hours a week.” As a thought leader on play and an advocate for balanced lives for kids, she says, “practicing that yourself is important.” Compulsive list-making and integrated projects (e.g., Substantial has office space at Playworks) is pivotal, as is an annual silent retreat, and daily meditation and exercise—running, biking, weight-lifting; “I spend as much time outside as is humanly possible.” A solo hiking trip to Yosemite this summer was followed by backpacking along Northern California’s Lost Coast Trail with Cushing, with whom she also has a blended family of five children. “Being a mom is a big part of my identity and mental energy and happiness,” she says—another piece of her balancing act.

Back at Laurel Elementary, a fresh batch of kids, sprung for a 20-minute recess, fans out across the asphalt. “I just like humans who, like, run,” Vialet says. “My kids do it going from the dining room to the kitchen, to get milk.” It’s natural. Yet, in playgrounds, parks, and backyards across America, kids are constantly admonished to stop running. “Oh, it’s so weird!” she adds. “So many school districts over the years have passed rules about no running, no tag. It’s mind-blowing.” Waving the kids forward, she calls out, “Run! Run!”—then shakes her head. “Sometimes you really have to wonder about grownups.”