“‘Anita sometimes reads the newspapers,’ Ma said, and then became quiet at the absurdity of her words,” writes author Akhil Sharma, J.D. ’98, in “If You Sing Like That for Me,” one of eight pieces from his new short-story collection A Life of Adventure and Delight. Anita, a lost young Delhi woman, is participating half-willingly as her parents introduce her to a series of potential husbands over dinner. She’s neither educated enough nor pretty enough to attract a man whom she might actually find compelling, and her parents have nothing interesting to report about her.

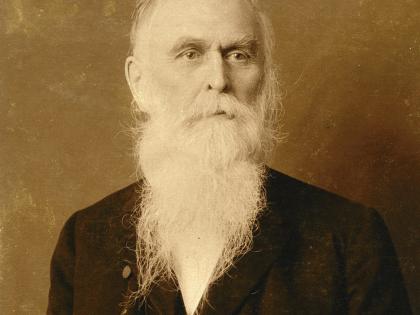

Courtesy of W. W. Norton & Company

Later, after she’s married, she falls in love with her husband for just one brief afternoon; every moment of their marriage outside of that is awkward and hollow. “What a good man, I thought, and was frightened, for that was not enough,” Anita narrates. “I knew I needed something else, but I did not know what.”

Anita is one of a recurring cast of Indian and Indian-American characters in Sharma’s fiction, damaged by their family relationships and unprepared to cope with repression and the disappointments of intimacy: a middle-aged man awkwardly learns to court his neighbor after his wife leaves him; an international graduate student destroys his first romance. The collection tracks Sharma’s writing career: some of the stories are two decades old (“If You Sing Like That for Me” was originally published in The Atlantic Monthly in 1995), some much more recent.

In his first novel, An Obedient Father (2000), Anita is revealed to have been sexually abused as a child by her father, Ram Karan, a corrupt civil servant. She grows into a meek and easily frightened woman, lacking any of the professional ambition of her more formidable sister. (In the short story, only an indistinct sense of personal failure, rather than early abuse, underlies the hollowness of Anita’s eventual arranged marriage.) At bottom, though, An Obedient Father is centrally concerned with the relationship of Karan’s increasing public corruption to his private depravity. “Because institutions aren’t as strong in India, politics are all based on personal relationships; there aren’t the same boundaries between personal and public,” Sharma argued in a recent interview. “I also believe if you behave badly in your public life, somehow that’s going to impact your private life. It might lead you to be more rigorously honest in your private life, but most likely it will lead you to behave badly in your private life.”

Karan’s private behavior is shaped not just by his escalating crimes at work (from petty bribe-taking to, eventually, political murders), but also by his childhood during the partition of India, when he had watched the massacre—at once random and systematic—of all the Muslim families in his village, their mutilated bodies strewn across the ground. The deaths were never acknowledged: “Every Hindu in the school and town, the only people I might have had a conversation with, must have known that the murders were occurring, because we hardly discussed them.” Sharma’s narrative blurs the distinction between state-sanctioned violence, and the violence between neighbors that feels, somehow, more personal than political; the violence of partition is later reproduced at the family level, in Karan’s household.

Most of Sharma’s characters, like Karan, go through conflicts animated by the structure of Indian society—arranged marriage, religion, the trauma of partition. “I have lots of relatives who are corrupt bureaucrats,” he remarks casually; as a boy, he emigrated with his family from Delhi to New York, and still returns to India regularly. But the author is less interested in ideology in itself than in how politics provides a backdrop to emotional conflict, and he only reluctantly thinks of himself as an immigrant writer. He wrote An Obedient Father not out of a special interest in sexual or political violence in India (though India, he says, “is a violent and sad country”), but to sublimate his personal feelings of guilt over a childhood swimming pool accident in which his older brother Anup was severely concussed. “That’s why I started writing from the point of view of a child molester,” Sharma says. “I wanted someone who could justifiably hate himself in the way I hated myself.”

More straightforwardly, though, the accident inspired his “Surrounded by Sleep” (a story from 2001, also included in the new collection) and his 2014 autobiographical novel Family Life, his most celebrated work to date. Both works follow Ajay, a young boy coping with the aftermath of his brother Birju’s brain damage, and draw their power from their capacity to defamiliarize the reader with the mundane. “His mother was on her side and she had a blanket pulled up to her neck. She looked like an ordinary woman,” Sharma writes in “Surrounded by Sleep.” “It surprised him that you couldn’t tell, looking at her, that she had a son who was brain-dead.” He paints the family’s misery with disarmingly transparent prose (techniques that have won him comparisons to Anton Chekhov, one of his favorite writers): “Ajay decided to use his devotion to shame God into fixing Birju. The fact that two religions regarded the coming December days as holy ones suggested to Ajay that prayers during this time would be especially potent.” Across his stories, many of Sharma’s sentences open, deceptively sterile, with “The fact that…”—followed by some false link between cause and effect that betrays his characters’ tragically flawed worldviews. They have too much faith that the universe, and other human beings, will treat them in predictable and humane ways.

Since he’s achieved professional success, Sharma says, he’s pivoted toward stories with a more forgiving point of view and ambiguous moral center: “In the way that I approach life there’s much more of a sense that things are going to be okay, and because things are going to be okay there’s a freedom both to let people behave badly and not judge them too harshly.” In “The Well,” originally published in The Paris Review last year, a man named Pavan gets Betsy, a woman he’s been seeing, pregnant; he’s been hoping this would happen all along, thinking it would force her to commit to him. It doesn’t, and Betsy has an abortion despite all efforts to convince her to marry him. “I started crying at how selfish I had been,” he thinks. “I had been cruel and indifferent and had learned nothing from my own life.” But the voice of Pavan’s mother surfaces the story’s more delicate orientation between cruelty and repentance: “What he did was not respectful,” she pleads with Betsy. “It was not kind. But good things can come from things that start badly.”

Sharma composed about half the stories from A Life of Adventure and Delight in the 1990s, still darkened by Anup’s condition and by his fear—triggered partly by the cost of his brother’s medical care—of not having money. He spent his early life repressing what he really wanted, and attended Harvard Law School, he says, only as a means to earn a living: “I just wanted to be able to read a menu left to right instead of right to left—meaning, not starting with the prices. I had no loyalty to law school.” He never actually practiced law, realizing that he could make more as a banker than as a corporate lawyer who defends them, and instead worked at an investment bank while he finished An Obedient Father. He’s categorical about his time there: “I just didn’t care. I would look away from the Excel spreadsheets and all the numbers would vanish from my head because it just did not matter at all to me. It requires double the effort if you don’t care.” His frank way of speaking mirrors a certain quality of his prose: deceptively clear, so that his world’s absurdity shows through.

Follow Marina Bolotnikova @mbolotnikova.