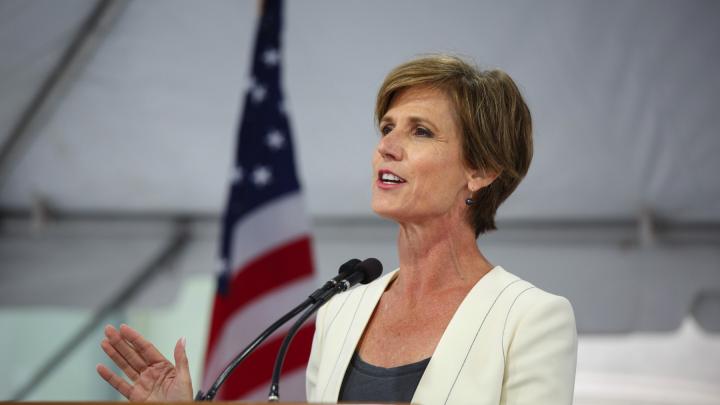

“It was supposed to be an uneventful time,” former acting U.S. attorney general Sally Q. Yates told Harvard Law School (HLS) degree candidates during her Class Day speech—even, as her former chief of staff joked, a time for “long, boozy lunches.”

Yates had agreed with President Donald Trump’s incoming team, as per tradition, that she would stay at the Department of Justice and “things would stay as they are” until Trump’s pick for attorney general, Jeff Sessions, was confirmed. No changes.

No executive orders that would, for example, ban travelers from seven (later six) predominantly Muslim countries. No ugly, finger-pointing fallout from an arguably illegal conversation between an American national security adviser and a Russian diplomat. No FBI questions. No public termination 10 days into Trump’s tenure for refusing to defend that order—and no ensuing congressional testimony. Yet for months Yates has had a reserved seat at the volcanic maelstrom of American culture and politics.

The experience, so far, does constitute a valuable lesson—for her, and for the 500 future lawyers sitting with loved ones in Holmes Field: “You never know when a situation will present itself in which you will have to decide who you are and what you stand for.” And quickly.

Yates said she had no time for self-reflection, or to examine the “weighty constitutional-law concepts at issue.” She had to act. Defending the order would have required Department of Justice (DOJ) lawyers to argue that it “was not intended to disfavor Muslims, despite the numerous prior statements by the president and his surrogates regarding his intent to effectuate a Muslim ban” that would have required “us to advance a pretext—a defense not grounded in truth."

The Georgia native, and former U.S. attorney for the Northern District of Georgia, grappled with whether to resign. That would have “protected my personal integrity,” she added, but not that of the DOJ. So she stayed and refused to defend the ban.

In the May 29 New Yorker profile of Yates, by Ryan Lizza, she relayed her reaction to being fired:

“Intellectually, I absolutely knew that this was a strong possibility,” she said. “But I didn’t want to end my service with the Department of Justice by being fired. Of course, I was temporary—I understand that. But, after twenty-seven years, that’s not how I expected it to end. Knowing something intellectually, and feeling it emotionally, as I am demonstrating right now, are kind of two different things.

The article also delves into Yates’s experience as acting attorney general and her role in the continuing Michael Flynn scandal, and looks at her childhood, along with her rise from private-practice attorney to deputy attorney general in the Obama administration.

Yates assured the HLS Class of 2017—the bicentennial class, and the first to have a 50/50 ratio of men and women—that the same compass that helped her decide to stay when the going got tough is “inside all of us—that compass that guides us in times of challenges is being built every day, with every experience.” She added, “You, too, will be faced with weighty decisions where law and conscience intertwine. The time for introspection is all along the way—to develop a sense of who you are and what you stand for. Because you never know when you will be called upon to answer [those questions].”

Her lesson number two: “The safest course is not always the best course. Be bold. Take a risk.” Those who take the easy routes are recognizable: prosecutors who won’t risk losing a case, so don’t try the hard ones; private-practice lawyers who tout the advice least likely cause a ruckus or make the firm look bad. Or, there’s the person who “never tells people in authority something they don’t want to hear”—and, conversely, the authority figures who surround themselves “with people who will simply affirm their judgment.”

These people “can rock along pretty well, make partner in a firm, advance up the corporate ladder,” she said. “But do you want to be that person? Would you find that a satisfying way to live? From my perspective, you may be advancing your career by practicing like this, but you’re not doing your job.”

Doing one’s job means getting things wrong sometimes—and owning up to it. It means taking chances, telling the truth. “And there’s nothing worse,” she added, “than the person who doesn’t want his or her fingerprints on anything controversial, who tries to slip out of responsibility when things hit the fan. Not only does that generally not work,” she continues, “if your colleagues sense that you’re going to cut and run if things go south, they’re never going to trust you. And if they don’t trust you, you’re not going to be included in the big moments—the moments you went to law school for.”

Yates took a risk and was fired. Earlier this month she testified before the Senate Judiciary Committee’s subcomittee on crime and terrorism. And she will likely continue to be questioned about what she knew, and how, and when, about ex-national security adviser Michael Flynn’s conversation with Russian ambassador Sergey Kislyak.

Near the end of her speech, Yates relayed “an old Irish story” she heard from a friend. A man arrives at the gates of Heaven, and wants to get in. “Saint Peter says, ‘Of course. Show me your scars.’ The man said, ‘Scars? I have no scars.’ Saint Peter replies, ‘Pity. Was there nothing worth fighting for?’”