On his last day in a Harvard baseball uniform, Josh Ellis ’17—senior captain, starting catcher, and practiced base-stealer—stole home. It was the second game of a doubleheader against division rival Dartmouth, on a wet and chilly afternoon that had spectators at O’Donnell Field huddling under umbrellas and later waiting out an hour-long lightning delay. Ellis’s stolen run came in the second inning, at the start of a rally that would lift Harvard to an 8-7 win against the Big Green, after dropping the afternoon’s first game 3-0. And that put the cap on a season of ups and downs—a roaring start and a big win in the Beanpot Tournament, and some early Ivy losses that led to mid-season soul-searching and a late course correction. The Crimson finished with a 19-23 overall record.

“A good game to go out on,” Ellis said later. He was thinking, especially, as he often does, of a teammate. This time, Austin Black ’18, whom a couple of injury-wracked seasons had kept out of the starting lineup—a broken arm, shoulder surgery, the mumps. “It’s frustrating,” Ellis said. “He hasn’t yet been the player he can be.” But on this day, Black had batted in three runs on three pinch hits and scored the game-winning walk-off. “So good to see that,” Ellis said. “An exciting way to end the season.”

That’s true for Ellis, too, who graduates next week and whose own collegiate career didn’t go exactly to plan. Recruited out of high school to Bowdoin College as a catcher (and swimmer and diver), he blew out his knee during his freshman year, trying to steal second base on an overthrown ball to first. Coming around the bag, he felt his leg buckle and heard a pop. The team was closing out a two-week road trip through Florida, and Ellis remembers flying home later that day, with his right knee braced up and massively swollen. He’d torn his ACL, MCL, LCL, and both menisci. After that semester’s final exams ended, he had surgery. It would be eight months before he stepped onto a baseball field again.

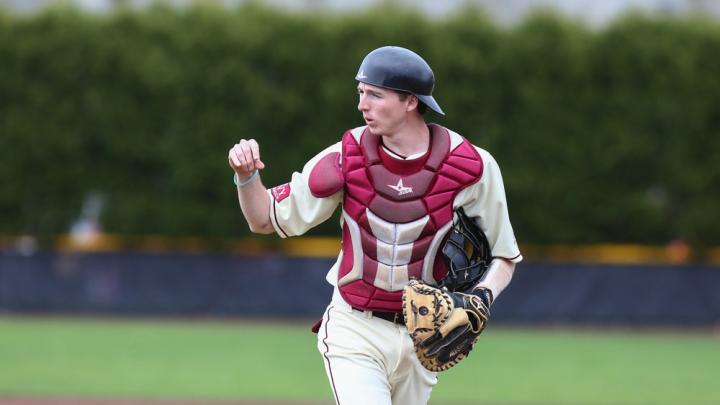

Ellis was the Crimson's leadoff hitter this season.

Photograph by Elan Kawesch

Even before the injury, Ellis had started to wonder if he was in the right place at Bowdoin. A “huge homebody” from Milton, Massachusetts, he felt far away there, even though the drive was just a couple of hours. The summer after his high-school graduation, he’d lost a close friend, who was struck and killed on her bicycle by a distracted driver. “It was the most absurd thing,” Ellis says. “We went from senior spring and ‘Life is good—we’re all going to college,’ to this unbelievable loss. And it was this moment where I was just totally confused as to what was going on. That kind of change and loss is hard to cope with.” Afterward, Ellis, who’d long planned on a medical career (the son of a cardiologist, he “grew up with a beeper in the house”), switched his interest from surgery to primary care and mental health. And, suddenly, heading off to college in southern Maine, “it felt like a world away.”

Ellis transferred to Harvard the fall of his sophomore year and joined the Crimson baseball team as a walk-on. A catcher ever since his Little League coach had installed him behind home plate when he was 10 years old, he bided his time in the outfield his first season in Cambridge, and practiced in the bullpen with the pitchers. “We had a senior captain that year”—Ethan Ferreira ’15—“who was killing it behind the plate, and hitting like .400,” Ellis says. “It was tough to crack the lineup.” But he did, and for the past two seasons was the team’s starting catcher and leadoff hitter. Last season he threw out nine of 22 base-runners, the second-highest pickoff rate for Ivy League starters, and as a batter made 35 hits and drove in 13 runs, with a batting average of .304. And he stole seven bases, the most of any Harvard teammate. This past season he stole six and had three home runs and 10 runs batted in. He led the Ivy League with 17 runners caught stealing.

“I love this kid,” said O’Donnell head coach Bill Decker earlier in the season. “I’ve been doing this for 32 years, and he’s one of the best young people I’ve been around.” As an athlete, Decker added, “he does the little things day in and day out”: working on his glovework, blocking and receiving, throwing, base-to-base running, the mechanics of the game. Plus, he’s fast. “Baseball’s not linear, home to first to second,” Decker explains. “Meaning, it’s a transitional speed game, change of direction, going with your instincts, reading baseballs, always knowing where the ball is.”

But when Decker says he loves Ellis, he’s also talking about something else—a patience and poise that seem years beyond Ellis’s age, an embrace of his teammates, his capacity for listening, for paying attention to who’s having a bad day and who might need a pep talk or a pat on the shoulder. Those things helped make Ellis team captain this past year. They also, in part, made him better at one of baseball’s most demanding positions. Catchers are, essentially, onfield coaches; besides catching and throwing and crouching down in the path of fast-moving balls, they must be able to call pitches and calm pitchers and make balls look like strikes to the umpires standing behind them. As the only players with the whole field in view, catchers read the game and translate it to their teammates.

Ellis loves throwing runners out—especially when it shifts the tide of a game, as it often does—but for him the most meaningful element of the position is the relationship with the player on the mound. “The trust between the pitcher and the catcher,” he says, “that’s really special. It’s one thing to throw guys out or block balls and prevent runners from advancing. But it’s a whole different thing being on the same page with one person.” When a bad throw or two leaves a pitcher feeling jittery, Ellis calls timeout and heads out to the mound. “Relax,” he’ll say. “This is just a game. Let’s play catch.” Other times he lights a hotter fire under the pitcher—depends on the pitcher and the situation. Going from the indoor wintertime practice field to the playing field can sometimes shake a pitcher’s focus, or cause them to lose confidence in their arms’ muscle memory. “A lot of the time for me, it’s just a matter of reminding guys that they’re really good pitchers and that they need to just focus in on my glove and not worry about anything else.”

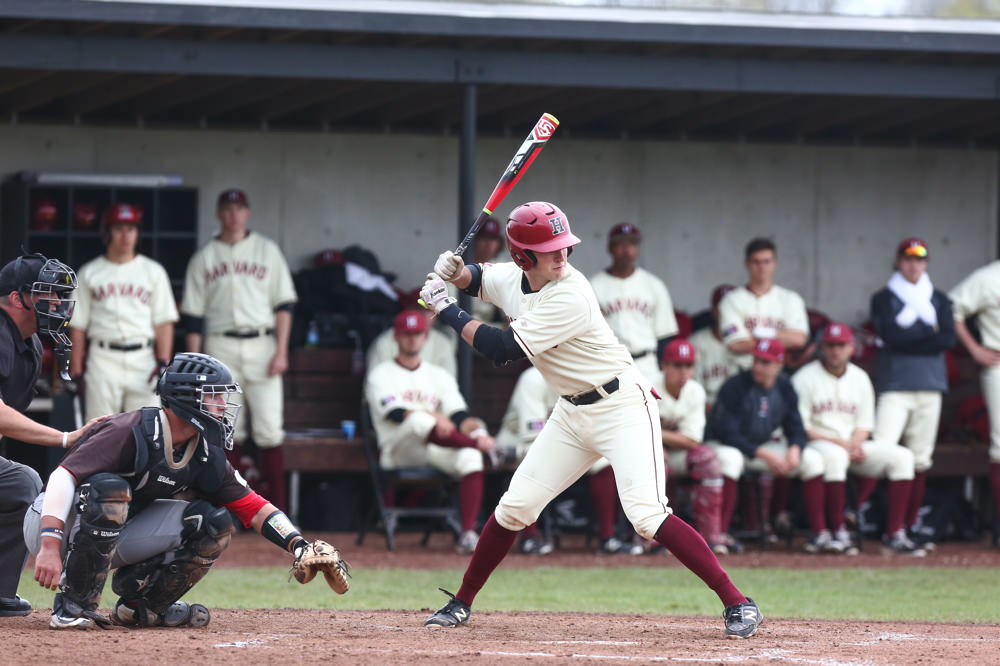

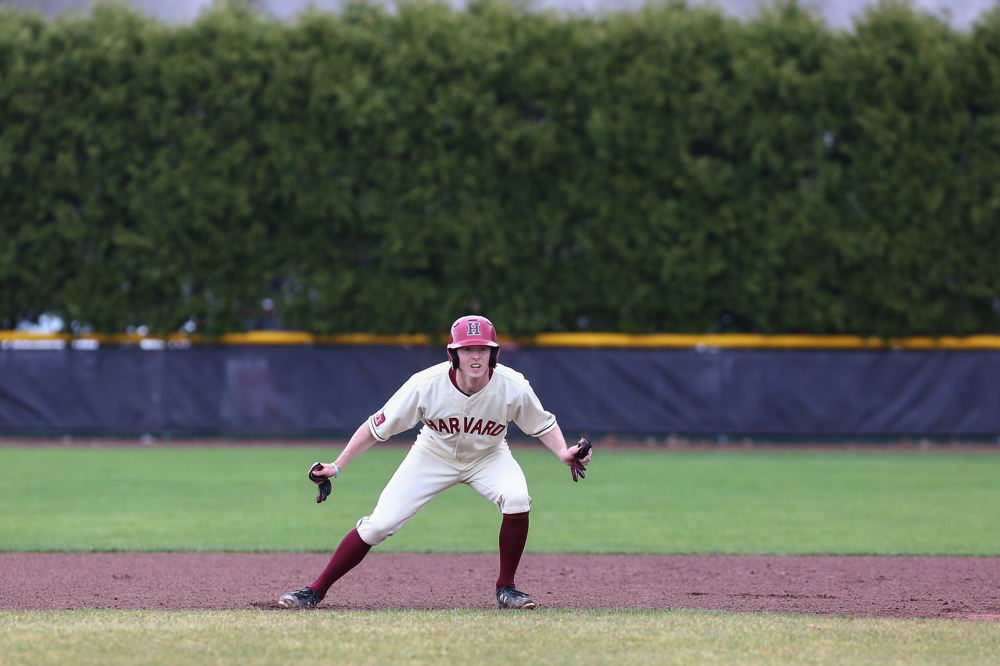

Base-stealing is an Ellis specialty.

Photograph by Elan Kawesch

Sometimes a catcher’s most important work can go unnoticed: practicing in the bullpen, “where it’s just the pitcher and the catcher, and the pitching coach is kind of walking around, and the guy’s throwing all his stuff and you’re getting a feel for how the pitching is working on that particular day.” In those moments, Ellis says, the catcher has the best vantage point on the pitcher. He’s looking at him straight on. The catcher can see the shape of the ball as it comes down the line, can feel the force of its velocity. “So you have a real opportunity to help the pitcher be the best that he can be for that given day.”

Now, for the first time since he was five years old, Ellis doesn’t have a baseball season in front of him—a much stranger feeling, he says, than graduating from college. “Baseball’s been something that’s characterized my life for quite some time. It’s really crazy being done.” With a degree in neurobiology, he will apply to medical school this summer, and he’ll spend a few weeks in Haiti, working with the Saint Rock Foundation, a health-care and social-services organization in Saint Rock, a tiny mountain town outside Port-au-Prince. His family first got involved with the group when a 12-year-old Ellis saw an ad in the church bulletin and asked his parents if they could go. Now they help run the foundation and spend weeks there every year. At Harvard, Ellis took classes in Haitian Creole so that he could talk more fluidly with Haitian residents than he could in his rudimentary French. He’s working to help establish a mental-health clinic in Saint Rock

But still: baseball. These past few weeks, he has fielded a couple calls from his high-school coaches about coming back to help out some. And he might make an appearance or two at O’Donnell Field. “I won’t be a stranger,” Ellis says.

No, he’ll be stealing home.