Four nights a week, anyone can saunter down to the lowest level of the Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts, buy a ticket, and slide into a cushy seat at the Harvard Film Archive’s (HFA) cinémathèque to view “rare and scholarly works of art, films that would otherwise be impossible to see,” says archive director Haden Guest—or at least see properly, in their original formats, and on a big screen.

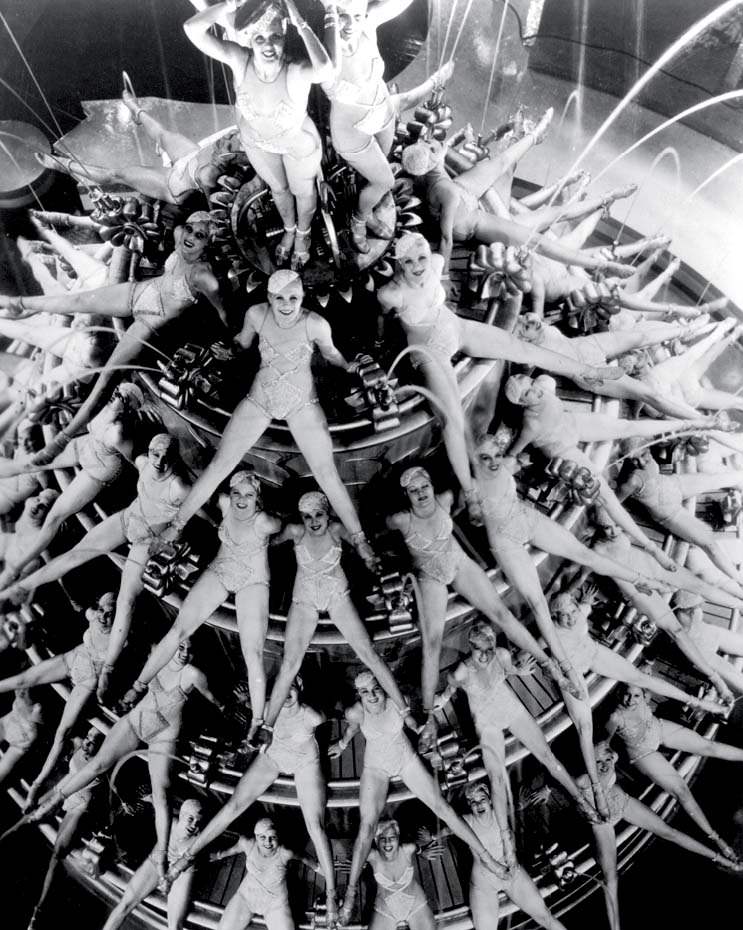

On tap this winter are typically disparate films. “Busby Berkeley Babylon” (December 9 through January 23) explores the Hollywood director and choreographer’s musicals, including Depression-era dazzlers like the archives’ own, hard-to-find, 35-millimeter print of Footlight Parade (1933), starring dancer-turned-actor James Cagney. Even now, the film’s “By a Waterfall” song-and-dance number featuring nearly naked “nymphs” and armies of synchronized swimmers forming elaborate geometric and floral patterns—filmed from above and underwater—is a delightful technical feat. “People may be surprised by the strange eroticism of some of these films,” particularly those from pre-Hays Code Hollywood, says HFA programmer David Pendleton. “These dance numbers really push the envelope: you have lines of chorus girls who are bent over at the waist and the camera travels down the line, between their legs.”

Film still from Busby Berkeley's Footlight Parade

Image courtesy of the Harvard Film Archive

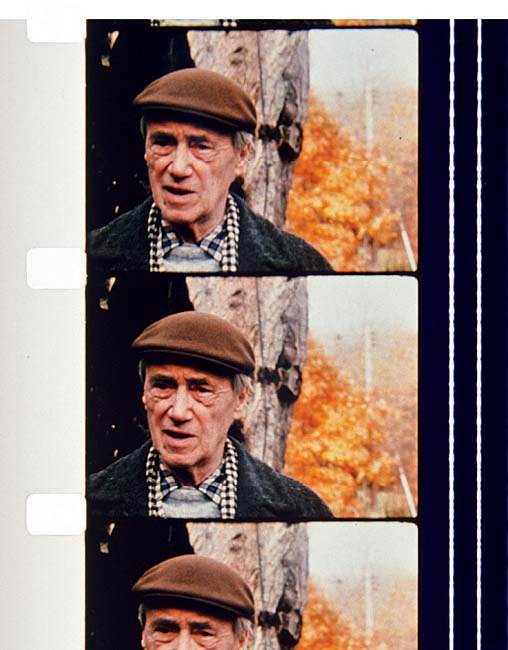

No less stimulating are the experimental, diaristic films of Lithuanian-American artist Jonas Mekas “Scenes from the Life of a Happy Man,” January 20-February 18). The prolific nonagenarian, considered the godfather of American avant-garde cinema, is still producing books and films and is scheduled to discuss his oeuvre in person, in conjunction with showings of Walden (Diaries, Notes, and Sketches) (1969) and Out-takes from the Life of a Happy Man (2012), on February 10 and 11.

The last time Mekas was on campus was in 1975, to visit his friend, the film scholar and curator Vlada Petric. At that time Petric was collaborating with anthropologist and documentarian Robert Gardner and with Cabot professor of aesthetics and the general theory of value Stanley Cavell to establish the HFA, which officially opened in 1979.

The HFA’s collection has since grown to nearly 30,000 titles, making it among the largest and most important university-based motion-picture archives in the United States, according to Guest. It encompasses “prints from across film history and from around the world, from Soviet silent films to contemporary American indie classics,” he reports, as well as home movies, shorts, animation, and experimental, avant-garde, and documentary films. In addition, there are more than 4,000 vintage posters, a growing store of filmmakers’ personal papers, and miscellaneous artifacts, animation models, technical manuals, and film equipment.

Alumni in the industry—including Terence Malick ’65, Michael Fitzgerald ’73, Edward Zwick ’74, Mira Nair ’79, Darren Aronofksy ’91, Andrew Bujalski ’98, and Damien Chazelle ’07—have contributed to the collection, and appeared over the years for HFA events. In November, during the series “Say It Loud! The Black Cinema Revolution,” the HFA hosted documentarian Kent Garrett ’63 for screenings of his Black GI (1971), a chronicle of combat soldiers’ experiences on and off the killing fields in Vietnam, and Black Cop (1969). The latter, he told the audience, explored “whether blacks should be cops,” and the complex roles they can play,through candid interviews with officers in New York City and Los Angeles during the height of the Black Power movement.

Still sobering and relevant, both films were made for Black Journal, the groundbreaking, public-television program co-developed by Garrett. On a national level, it represented the “first time blacks had a say in what was going on” in current events and how the media represented them, Garrett told the audience during the post-screening question-and-answer session.

From Walden, by avant-garde filmmaker Jonas Mekas

Image courtesy of the Harvard Film Archive

“History comes around,” he said, when asked about Black Cop’s relevance to current debates over the role of police and their relationships with minoritiy communities—although, he added, “the level of brutality then was not at the level, in terms of shooting black men, that it is today.”

Also shown was a stirring clip from Garrett’s work-in-progress, The Last Negroes at Harvard, about his 1963 class of 18 men and one woman who, in 1959, were the largest single group of blacks ever admitted to the College. “They came into Harvard as negroes,” Garrett said of the era, “and left as blacks.” Throughout his career, the news journalist and filmmaker has “always believed” in the power of “the media, video, and news to really change peoples’consciousness,” he said, “and that’s what I’ve always wanted to do.”

The point of the archive is, after all, to educate. Its film holdings alone have grown three-fold since Guest arrived a decade ago, and the general archives have expanded through gifts like the Lothar and Eva Just Film Stills Collection, containing about 800,000 items, pledged in 2009.

Meanwhile, Guest recently announced another windfall: the complete papers and films of experimental American director Godfrey Reggio. The documents will become part of the Harvard Theatre Collection at Houghton Library, Guest says, “and people can step next door here to study his films.” Reggio is best known for his profoundly prescient 1980s Qatsi trilogy (Koyaanisqatsi, Powaqqatsi, and Naqoyqatsi), which depicted, solely through poetic images and music, the modern destruction of the environment.

The materials also cover Reggio’s early years as a monk working with youth gangs during the 1960s Chicano nationalist movement, says Guest, and his subsequent “media saturation campaign to raise consciousness about the kind of government surveillance taking place in the name of ‘social security.’ Reggio was, and still is, way ahead of his time.”

A movie theater, classroom, and library, the HFA’s structure is uncommon among universities. The year-round cinémathèque’s public programs, funded by admission fees and tiered-membership dues, are often paired with visits by guest artists—directors Ang Lee and William Friedkin, actress Angela Lansbury, and Canadian filmmaker Guy Maddin, among them.

Yet its core mission is to support study and teaching at Harvard, and to maintain its resources for scholars everywhere. (As such, it was moved administratively from the department of visual and environmental studies to the Harvard College Library; see “Cinema Veritas,” November-December 2005.)

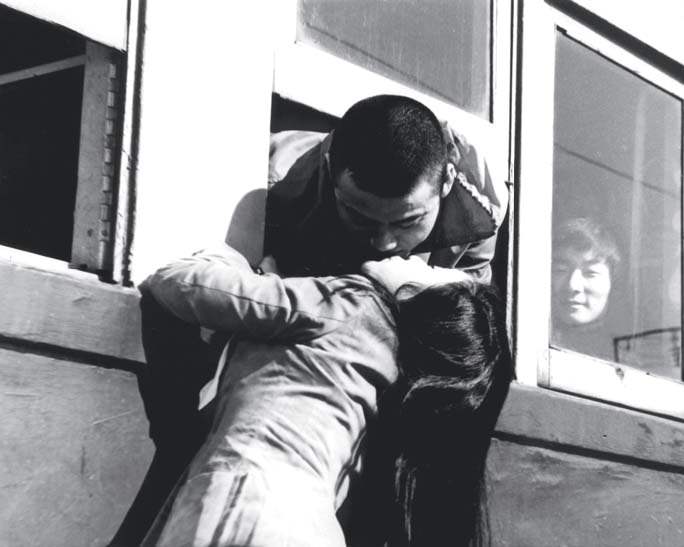

Hi Gil-Jong’s March of Fools

Image courtesy of the Harvard Film Archive

This winter, Guest researched and curated “Ha Gil-Jong and the Revitalization of Korean Cinema” (February 3-27)—the first retrospective of the 1970s South Korean artist outside his own country. Ha’s films are wrenchingly “emblematic of the struggles of an artist working under the totalitarian regime of [then-president] Park Chung Hee,” Guest explains, “at a time when cinema was expected to toe the party line.”

An orphan, Ha traveled to America as a young man and wound up in California, where he was the first Korean to earn an M.F.A. and a master’s degree in film studies at UCLA before returning to South Korea. There he rejoined a circle of artists and political critics, and produced his feature films. In his salient and affectionate March of Fools (1975), which was a surprise commercial hit, disaffected university students search for love and meaning. Ha “used richly ambiguous narrative and imagery to show that things are not as they might appear, revealing deeply planted seeds of discontent,” Guest notes. Unfortunately, the success also drew attention from censors and made it harder for Ha to produce more such innovative work. He died of an “alcohol-induced” brain aneurysm at age 38, according to Guest.

Ha is not widely known in the West; the HFA had to borrow prints from the Korean Film Archive. Yet his work, Guest suggests, like that of Busby Berkeley, can teach viewers about how to learn from history and engage in the world. Berkeley reveals aspects of how life was lived during the Depression, responses to the onslaught of automation, and the rise of media-driven sexual currency. Ha offers the perspective “of Koreans living under a military dictator at a time when there is political oppression here and around the world,” Guest says. “These films can help us find and forge the freedom we so urgently need.”

As Harvard strives to elevate the arts on campus, Guest is among those coordinating resources among the libraries, museums, and arts departments, and promoting more interdisciplinary events.

In October, the HFA and the Hutchins Center for African and African American Research presented “Pam Grier, Superstar!” It looked at Blaxploitation and other films reflective of African-American experiences and the cultural upheavels of the 1970s; Grier’s protagonists, the HFA stated, are “defiant, authoritative, resourceful vigilantes whose intellectual, physical, and sexual adeptness American movie screens had never experienced the likes of before.” The actress was at Harvard to receive the Hutchins Center’s 2016 W.E.B. Du Bois Medal, and spoke about her life and work following the HFA screenings of Foxy Brown (1974) and Jackie Brown (1997), Quentin Tarantino’s homage to her and the tumultuous era.

Guest and Pendleton were also instrumental in organizing “Houghton at 75,” inspired by holdings at that Harvard library. The March series includes Jane Campion’s Bright Star (2009), a fictional account of John Keats’s last years; Peter Ustinov’s Billy Budd (1962), adapted from Herman Melville’s novel; and Warren Beatty’s Reds (1981), based on the life of journalist John Reed, A.B. 1910.

British filmmaker Terence Davies, a past HFA guest, will also be on hand for a screening of his film about Emily Dickinson, A Quiet Passion (2017), for which he made previous trips to Harvard to pore over the poet’s hand-sewn manuscript books and letters at Houghton. The series reveals how “the spirit of the original literature lives in the films,” Guest says. “Cinema is not just entertainment, not just a complement” or a mode of elucidating other disciplines, he asserts. “We are dedicated to presenting, exploring, and breaking new ground, and to showing cinema to be at the same level as great literature.”