Fluffy the cat lounges beside a campfire, licking herself on a nippy spring day. A black pug named Wizard trots over, barking at his companion, an old beagle called Freedom. The two paw at each other and are rolling around in the dirt as Debra White appears. “Now, come on,” she says, bending over to stroke them, and they cheerfully run along. Then she turns to greet human guests arriving at her Winslow Farm Animal Sanctuary, in Norton, Massachusetts. “You can touch the animals—if they want you to. But not the pot-bellied pigs," she explains. “Go up in the back under the pine trees to see the donkeys. They’re out with the alpacas. Please make sure you close the gates behind you.”

With these simple rules, visitors are unleashed to explore the 16.5-acre site that is a “home for life” for 132 abused or abandoned animals. White founded the farm 20 years ago and depends on a crew of devoted volunteers, adults and teenagers, to keep it open to the public year-round. “There’s no other reserve around like this, where the animals are so free,” says volunteer Ron Mollins, who has been helping out since 1998. “We don’t have lions or tigers, but if you really want to get to know animals, this is the place to do it.”

Dozens of cats roam the grounds, while goats, mini-horses, rabbits, and emus peaceably share a corral. Harmony tends to prevail because their needs are met, White suggests: there’s nothing for them to fear. Nine separate feeding stations mitigate competition for food, newcomers are thoughtfully integrated, and their living quarters, cleaned daily, are rotated over time, she adds, “so they don’t get bored.” Many of the cats, like black, amber-eyed Velcro asleep by the aviary, have been thrown over the farm’s roadside fence at night. “That happens,” White reports, wearily. “We find them in carriers in the morning. No notes, nothing telling me anything about them. One time we had 23 rabbits dumped over—it took us days to catch them all and then they all had to be spayed and neutered so they wouldn’t reproduce.”

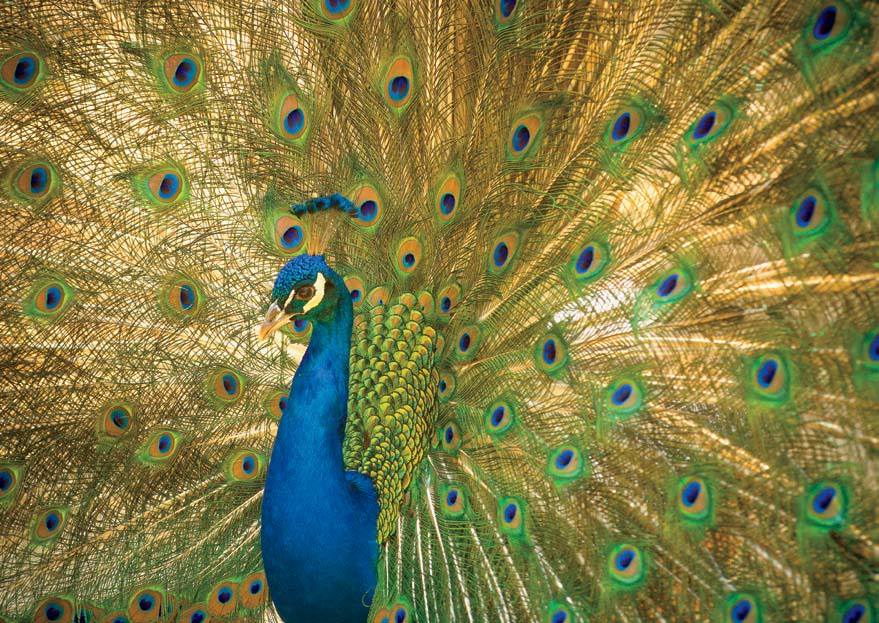

White took in Athena, the black-nosed sheep, after the Animal Rescue League of Boston found her living on a median strip off Route 495. An Indian indigo peacock, now at least 30 years old, has been at Winslow Farm for more than half his life. During a recent visit, he was in full wooing form, fanning and quivering his six-foot spread of iridescent blue and green feathers at potential mates. White says that when she first saw him, he was living in a four-by-four-foot cage with “feces caked on his plumage.” Every day White gets calls about animals in trouble or in need of a home. It’s wrenching to turn any creature away, but the farm runs on a $200,000 annual budget dependent on visitor admission fees, fundraising, donations, and grants, and is at capacity. “I try to teach people—and they should teach their children that responsibility—that when you get an animal, it is yours to care for. The way you treat it at first, when it’s a baby, should be the way you always treat it throughout its life,” White explains. “These are not little pieces of disposable trash.”

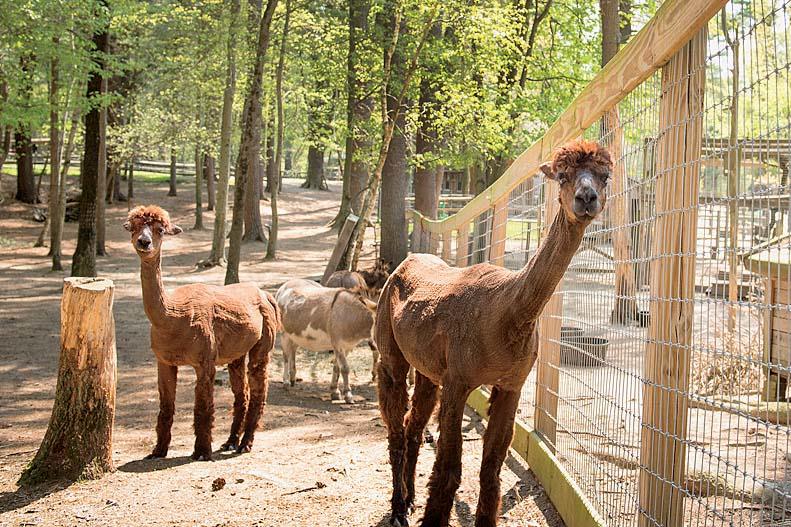

The farm lies between a country road and Meadowbrook Pond. An old pine grove shades the chunk of land where the donkeys and alpacas were hanging out recently while a farrier cleaned and trimmed their hooves. Visitors are free to watch, ask questions, and learn. A few slowly approached the three donkeys and laid hands on their manes, smoothing down the fur. The four alpacas have big, liquid eyes, but are skittish; a calm approach occasionally yields a silky touch of their chocolate-colored fur.

The horses and mini-horses are in paddocks, where volunteers accompany visitors, but rabbits are out and about, and doves fly in and around the aviary, where Jin (a red, blue, and yellow pheasant found in the parking lot of the Toys “R” Us in North Attleboro) lives with the peafowl. Chickens peck and squawk here and there, often congregating with the roosters, Harry and Larry, at the far end of the property, on the porch of the David Sheldon White Resource Center, which houses events, educational programs, and even beds for volunteers who travel from afar.

White built it, as well as her own wood-framed house, and other beguiling structures scattered around the landscape. Sheds, cabins, chicken-wire enclosures, and even a tiny chapel to commemorate residents who have died, are often flanked by wildflower and herb gardens, or shrouded by wisteria. The handsome, hexagonal stone barn with round windows, a skylight, and a shingled roof, was constructed this past winter for the donkeys. Visitors also gather at play zones, picnic tables, or around a fire pit.

The place has a storybook feel. Visitors sit on bentwood furniture to watch the paddock, or wait for animals to wander by. Geese favor the hand-dug pool, banked by rocks. Dozens of stone animal statues are tucked into nooks or stand on pedestals in the gardens, offering the makings for an impromptu treasure hunt. Children are encouraged to explore and simply spend time with the animals, without any agenda. And unlike at petting zoos, no attempts are made to hide the evidence that this is a farm—manure and mud, dust, dirt, loose feathers and fur, food scraps, hay, grain, tractors, hoses, ropes, shovels, and sludge buckets—or the endless labor required to run it.

Founder Debra White

Photograph by Stu Rosner

Belle, a Hafflinger saved from slaughter

Photograph by Stu Rosner

Peacocks, free to spread their tail feathers

Photograph by Stu Rosner

Residents include alpacas, freshly sheared for summer

Photograph by Stu Rosner

A pig and sheep enjoy the sun

Photograph by Stu Rosner

Play areas for all ages blend in with the “storyland” ambiance.

Photograph by Stu Rosner

A play and picnic spot

Photograph by Stu Rosner

Since 1996, White says, she has taken only five days off. Three were spent in the hospital undergoing knee surgery, a break that “felt like a European vacation,” she says, laughing. Yet the farm offers a familiar routine. White grew up in a nearby log cabin, and helped care for her father, David Sheldon White, who had been a “genius inventor for Texas Instruments in the 1950s,” she says, but was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease by the time she was three. “The way I had to communicate with him was to be very quiet and observant. We didn’t talk very much,” she explains; often, she was her father’s hands, building what he could not. She also spent significant time outside, playing in the woods by herself, or in the company of her pets. “They were my happiness, they were always there for me and brought me through a lot,” she says, as did the sights and sounds of nature and its animals. “To this day, I feel I am in heaven on earth to be here,” she adds. “I think a lot of people are just missing out on the simple things that are offered to us.”

Winslow Farm is located on property that was owned by her father’s family until it “was lost due to his illness,” she says. In her twenties, White, who attended college for a year before choosing to stay home and care for her father full time, decided to buy back a portion of the land and build a sanctuary. Working at three jobs (including as a veterinary assistant), she eventually saved enough money to do just that.

“I call her the ‘Jane Goodall of Norton,’” Ron Mollins says while tending the campfire behind White’s house. He comes every day for at least three hours to chop wood, rake, clean up—whatever “she asks me to do.” Still, “I get more out of this place than I put into it,” he adds. “It’s magical—the way life should be, and could be. It’s a nourishing place, nourishing to the spirit.” White has never strayed from her initial, core mission: to rescue and care for maltreated animals. She also promotes animal welfare and the conservation of natural habitats, offering barnyard tours, educational programs, and a partnership with nearby Wheaton College. Students, she says, “come to observe alternative lifestyle living” as part of courses on religion and philosophy, to study animal psychology and training techniques, or sometimes to do empirical research. (They have worked with the farm’s miniature horses, assessing their cortisone levels, heart rates, and behaviors.)

When networking with other animal-rights and rescue organizations, White is happy to share information, but her daily duties are too demanding for much formal political activism. Even adopting out animals she rescues—which she used to do, especially when she had about 300 animals on site—takes too much time and effort; too often adopters “did not realize what they were getting themselves into” and returned the animals.

At one time she dreamed of expanding the farm to include a charter school, trails and campsites, and an on-site holistic veterinarian. Now, she says, “my goals are completed. We are running as is.”

It’s enough. Recently a visitor sat down by the aviary and watched the peacock strut and call. A brindle cat came over and curled up in the sun. White doves flew by. A llama loped up. “The animals read each other and if they don’t see any fear, then they are all just cool and they’re laying around together,” White says. “I constantly know exactly what everybody needs here, without a hesitation, on a daily basis, even when they are sick, because I am quiet and always watching.” People, she adds, “don’t really stop and observe and experience what’s going on around them. If humans didn’t have voices, I think we’d all be better off.”