Connoisseurs have long celebrated—and collectors craved—the beauty and technical brilliance of Chinese ceramics: the floral exuberance of Qing dynasty vases; Ming blue-and-white ware; mellow green celadons and subtly exquisite Northern Song Jun porcelains in unequaled blue and plum tones; tricolor Tang horses and camels (some nearly life-size). Now, a highly focused, technically outstanding exhibition at the Harvard Art Museums (HAM) casts the viewer’s gaze almost incomparably farther back in time, to one of the foundational origins of this masterly craftsmanship.

Prehistoric Pottery from Northwest China, on display through August 14, presents nearly five dozen examples of earthenware ceramics dating from the Neolithic Yangshao culture (5000-3000 B.C.E.)—including delicate bowls and elongated amphorae with textured surfaces, survivors of seven millennia—to the Qijia culture (2200-1600 B.C.E.) and successors, coterminous with the nascent Bronze Age—featuring appealing animate forms, but in some senses surprisingly less refined construction and decoration than that of earlier eras. The sheer antiquity, size, and state of preservation of the objects resonate, as does the sense of discovery that comes from the work under way to understand their creators’ communities and cultures, whose existence has been rediscovered only within the past century.

The exhibition provides a clear, chronological survey of Neolithic Chinese earthenware.

Photograph by R. Leopoldina Torres/Harvard Art Museums

The exhibition, in the museums’ third-floor University Study Gallery (used during the academic year for student- and course-related exhibitions)—and, for the most part, vividly available online, with helpful maps and explanatory materials—is also a robust demonstration of the joint potential of Harvard’s scholarly capital, museum and library collections, conservation expertise, renovated HAM resources, and global intellectual reach.

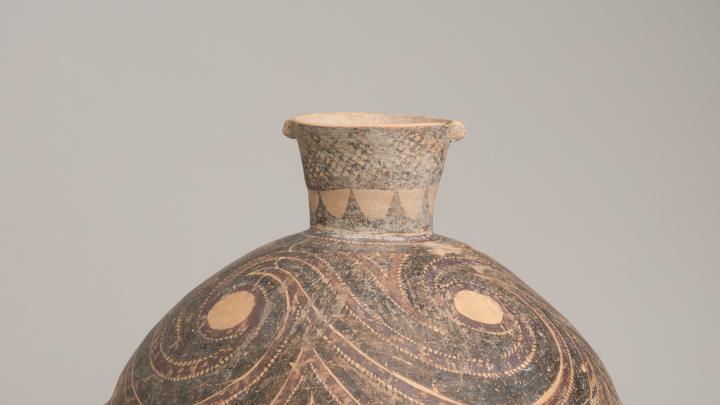

Its genesis was Hudson professor of archaeology Rowan K. Flad’s service as organizer of the seventh worldwide Society for East Asian Archaeology conference in Boston, June 8-12, which brought together several hundred leading scholars in the field. As Flad’s own excavations turn toward northwestern China, he recognized that the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology’s important ceramic holdings from the area might merit exhibition for the guests. (The showpiece in the exhibition, a magnificent Majiayao vessel [3300-2650 B.C.E.] from the Peabody collection, was reproduced as the cover illustration for both the conference program and the fourth edition of a classic, The Archaeology of Ancient China, near at hand on Flad’s shelf, written by Kwang-chih Chang—a previous holder of the Hudson professorship.) Flad reached out to Hung Ling-yu, assistant professor of anthropology at Indiana University, an expert in the settlement patterns, burial practices, and pottery of the Yangshao and Majiayao (3300-2000 B.C.E.) cultures. (Closing the Harvard circle, Hung said in a recent conversation in the gallery that a class she took with Kwang-chih Chang in the late 1900s in Taiwan, and her course paper on the Yangshao culture, sparked her interest in the field and led to her academic career.) She spent the past academic year as a visiting fellow at the Fairbank Center, organizing the exhibition. Finally, Flad taught a freshman seminar this past spring on ancient Chinese technologies, including the earthenware pottery (the class even made a field trip to Harvard’s ceramics studio, operated in Allston by the Office for the Arts, for hands-on experience).

Although the culture of the ancient upper and middle Yellow River valley, and contemporary excavations, could not be farther from the refined setting and controlled atmosphere of the HAM complex, Hung described two significant learning experiences from organizing the exhibition.

First, although she and Flad had focused initially on the Peabody holdings, which are embedded in archaeological context from their discovery before World War II, she subsequently discovered that the art museums have an even larger collection, assembled by acquisition from dealers by Walter C. Sedgwick ’69, with assistance from Robert D. Mowry, former Dworsky curator of Chinese art—a collection that came to the museums by gift and acquisition in 2006.

Second, understanding those works—which are naturally removed from the explanatory context of an archaeological dig—depends on analysis of artistic styles, technical examination of pigments, and other tools familiar to HAM curators and experts from the Straus Center for Conservation and Technical Studies. For example, ultraviolet (UV) illumination and Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) can discriminate between ancient and modern pigments, helping to determine whether a vessel is original, retouched or altered to enhance its appeal for the contemporary market, or a modern replica. This application of museum-based techniques of analysis, Hung said, was new to her, and now complements her core work of scholarship embedded in discovery and interpretation of materials and cultures in archaeological context. Both HAM and the collector, she noted, were completely open-minded toward, and receptive to, the analysis of each object; those on display are considered, with reasonable confidence, to be authentic.

Changing Cultures, and Interpretations

The initial, small case in the exhibition underscores how recent the discovery of these Neolithic communities is, and how much work needs to be done to understand them. It includes Anau potsherds from the Peabody collection, discovered in southern Turkmenistan (in central Asia) in the early 1900s. One of the most significant artifacts is reproduced in a rare book, on display from the Tozzer Library; it documents Swedish explorer J. G. Andersson’s 1920s Yangshao discoveries, from Henan province, and his resulting conclusion that Chinese ceramics arose from the west—and were therefore of Eurasian, or perhaps even European, origin. (That theory is no longer held; the technology is documented from eastern, coastal regions in China.)

The heart of the exhibition appears in a full-gallery-length set of cases, beginning with that landmark Majiayao vessel, but then stepping back to proceed chronologically from the Yangshao culture through Majiayao and Qijia cultures—the latter reflecting, among other changes, the transition from coil-built to wheel-thrown fabrication.

An initial impression is simple wonder that very large earthenware objects could survive so well. Northwest China’s dry climate certainly helped. So did local customs: burial sites (the source of most of the objects, which had funerary uses) were pits filled with earth, noted Melissa Moy, Dworsky associate curator of Chinese art (Mowry’s successor). Elsewhere in China, tombs were covered with timber roofs, which typically collapsed at some point, shattering the contents below.

Another impression is what Moy described as the obviously “robust, painted, dynamic decoration,” from the earliest documented era. Some of the Yangshao pieces are simply fired, or textured with ribbing or impressions made with a cord. But others, including delicate bowls, are glazed around the lip, in russet. The Majiayao works feature appealingly modern, abstract, geometric patterns, typically in black glaze over the reddish clay. But there are also those strikingly animate motifs—perhaps frogs or tortoises, maybe in water, circling a side jar. And later Majiayao works have bicolor glazing. All these colors, and the details of the vessel shapes, are richly illuminated; because the works are not light-sensitive (unlike fragile drawings, for example), the exhibition designer was able to turn up the candlepower.

Mysteries requiring further scholarship arise. Certain Majiayao vessels are masters of craftsmanship: the shapes perfectly symmetrical, the clay coils smoothed to a fine texture with paddles before glazing and firing; the brushwork sure and exact. Others are cruder in form, lopsided, and clumsily decorated, or even unpainted. Were these the work, respectively, of master and apprentice-learner? Did they come from different workshops? Are finer vessels tradeware, and others for everyday use? (Hung said most excavated vessels are found empty, but occasionally traces of millet, or impressions of barley, have been discovered.) Do some pieces accrue to people of higher status? The answers to all these questions are to be determined, if possible, archaeologically.

And then why, turning to the later, and relatively less understood Qijia culture and successors, did the decorative glazing become radically less complex—even as the pottery forms become more elaborate, with jars built with swooping necks and fluted edges, and, finally, inlaid decorative stones and turquoise? Were the most skilled workers now engaged in shaping bronze, or were the most ritually significant objects now made in that material? What was the impact of other changes in domestication of animals, and trade? (Visitors may resonate especially to a tiny rattle with a long neck and pointed snout; a covered jar with handles and a tall cover with a stylized human head atop a giraffe-worthy neck; a sort of a short-legged cow-pig with a delicate muzzle that might be comfortable alongside Dr. Dolittle’s pushmi-pullyu; a tiny jar astride what could be a pair of wellington boots; and a geometrically decorated Xindian culture (1600-600 B.C.E.) cup with a single handle that somebody from Starbucks might want to knock off.)

A final case addresses material culture—clay from the Majiayao region, in raw and processed forms; hematite, a pigment source—and modern-day reproductions, using different techniques (the wheel, different pigments), created by local master craftsmen Yan Jianlin and his son, Yan Xiaohu, who live near the type site for Majiayao discoveries.

Experiencing What Is Known—and Not

The state of what is known is best described on the exhibition website (linked above)—a version of which is available on smartphones, an experiment being conducted by the museums, for exhibition visitors (harvardartmuseums.org/tour/prehistoric-pottery-from-northwest-china).

To the extent that deeper understanding of these ancient objects and their makers is achieved, it will come through the sort of cooperative venture that led to this exhibition: research by scholars like Flad and Hung; their teaching, from graduate students to Flad’s freshman seminar; the melding of formerly separate collections, like those in the Peabody and the HAM holdings; the application of archaeological and art-analytical approaches; and educational exhibitions at the highest standards of contemporary museumship. Melissa Moy said of Flad’s work, from the conference through the freshman seminar and the organization of the exhibition, “He’s really tapped into everything we want to do at the museums”—use of the gallery itself, of course, but student engagement in the art-study centers and materials lab, the Straus conservationists, and more.

That important work aside, this inaugural co-presentation of the Peabody and art museums’ Neolithic collections has yielded a beautiful exhibition that may appeal to even the casual visitor. Those who wish to go deeper may want to sign up for a gallery talk on July 14, led by Elizabeth La Duc, a Straus Center objects conservation fellow, and Yan Yang, curatorial assistant for the collection.