What are the ingredients of a healthy, inclusive society—one that offers its citizens opportunity, happiness, and a positive quality of life? According to Lawrence University Professor Michael E. Porter, models of human development based on economic growth alone are incomplete; nations that thrive provide personal rights, nutrition and basic medical care, ecosystem sustainability, and access to advanced education, among other goods—and it is possible to measure progress toward providing these social benefits.

Porter’s 2015 Social Progress Index (SPI)—released in April and developed in collaboration with Sarnoff professor Scott Stern of MIT’s Sloan School and the nonprofit Social Progress Imperative—ranks 133 countries on multiple dimensions of social and environmental performance in three main categories: Basic Human Needs (food, water, shelter, safety); Foundations of Wellbeing (basic education, information, health, and a sustainable environment); and Opportunity (freedom of choice, freedom from discrimination, and access to higher education). Porter considers the index “the most comprehensive framework developed for measuring social progress, and the first to measure social progress independently of gross domestic product (GDP).”

The index, he explains, is in some sense “a measure of inclusiveness,” developed based on discussions with stakeholders around the world about what is missed when policymakers concentrate on GDP (which tallies the value of all the goods and services produced by a country each year) to the exclusion of social performance. The framework focuses on several distinct questions: Does a country provide for its people’s most essential needs? Are the building blocks in place for individuals and communities to enhance and sustain well-being? Is there opportunity for all individuals to reach their full potential?

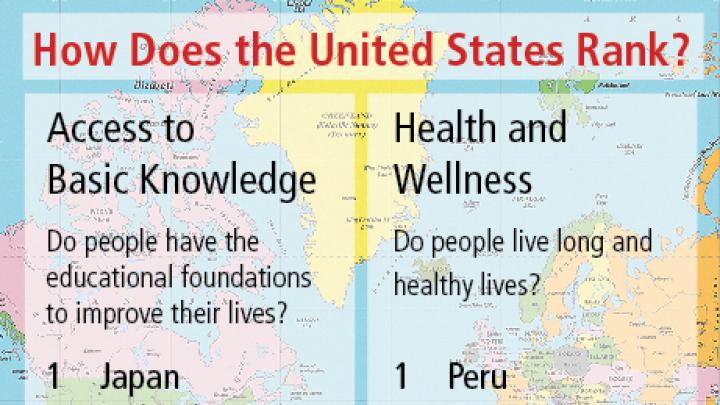

The United States may rank sixth among countries in terms of GDP per capita, but its results on the Social Progress Index are lackluster. It is sixteenth overall in social progress: well below Canada, the United Kingdom, Germany, and Japan in several key areas, including citizens’ quality of life and provision of basic human needs. The nation ranks thirtieth in personal safety, forty-fifth in access to basic knowledge, sixty-eighth on health and wellness, and seventy-fourth in ecosystem sustainability. “We had a lot of firsts in social progress over the years in America,” Porter points out, “but we kind of lost our rhythm and our momentum.”

About 20 or 30 years ago, for reasons Porter says he cannot completely explain, the rate of progress in America began to slow down. As a society, he points out, Americans slowly became more divided, and important priorities such as healthcare, education, and politics suffered. “We had gridlock, whether it’s unions or whether it’s ideological differences, and—although we’ve made some big steps in certain areas of human rights like gay rights—if you think about the really core things like our education system and our health system, we’re just not moving,” he says. “I think our political system isn’t helping, because we’re all about political gains and blocking the other guy, rather than compromising and getting things done.”

Meanwhile, he notes that even though other fast-growing nations such as India and China haven’t been able to attain a level of social progress commensurate with their economic progress either, certain countries such as Rwanda have “knocked the cover off the ball” in terms of social progress. “They went through a genocide, were devastated, and, to bring the society together, there was a consensus, led by the president, that their first job was to re-energize and restock the society and the capacity of their citizens,” he says. For example, the country achieved a 61 percent reduction in child mortality in a single decade, and today, primary-school enrollment stands at 95 percent. Rwanda also ranks high for gender equity, as women constitute a majority of the parliament—partly he says, because a lot of men were killed, but also because the country set out to be a place where women are not just equals, but leaders.

Porter hopes his continuing work on the index will help explain why the United States is “doing poorly” relative to other countries that are doing well. His team had “a pretty big mountain to climb” just to get the SPI recognized by national leaders and scholars, mainly because GDP has become the main way of measuring a nation’s success. The goal now is to get the United States to use their tool at the state and city level to assess local performance, and then set priorities for improvement.

In terms of progress for the average citizen, Porter warns, the United States is more threatened now, globally and economically, than it has been in generations. This phenomenon, he argues, reflects a legacy of anti-progressive politics, as well as bad economic policy. As a result, “We can’t fix our tax system, we can’t improve our infrastructure, we can’t deal with our public schools, and we can’t rein in this excessively costly legal system that we have that doesn’t necessarily achieve better results.”

Yet the Social Progress Index, Porter hopes, could prove to be a useful tool that will propel America in the right direction. He is currently working with leaders on the national level in several countries, including Brazil, Colombia, and Paraguay, where the SPI is a core element of their national development plan. “Now the general awareness is that this is a critical tool and a necessity—people are starting to use it in thinking about how we [achieve social progress] in our country, in our society, in our region, in our city,” he says. “We’re encouraged—but we’ve got a long way to go.”