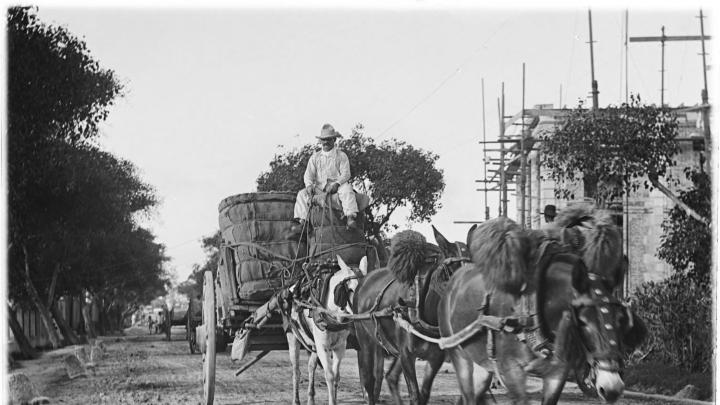

The United States flag flying over the governor-general’s palace in Havana (see the second image in the photo gallery, above). American construction prowess applied to restore roads and bridges left crumbling by the former occupying colonial power. Such images could not have been taken in Cuba during the past half-century. Even after the reopening of embassies this past August, a symbolic thawing of a frozen Cold War relic, the U.S. relationship with Cuba has a long way to go to become fully normal.

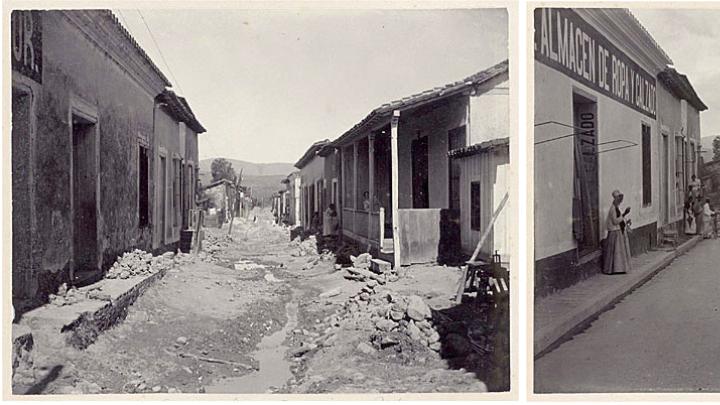

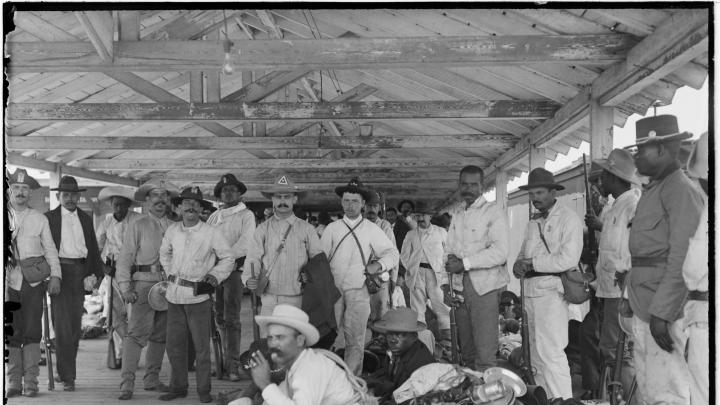

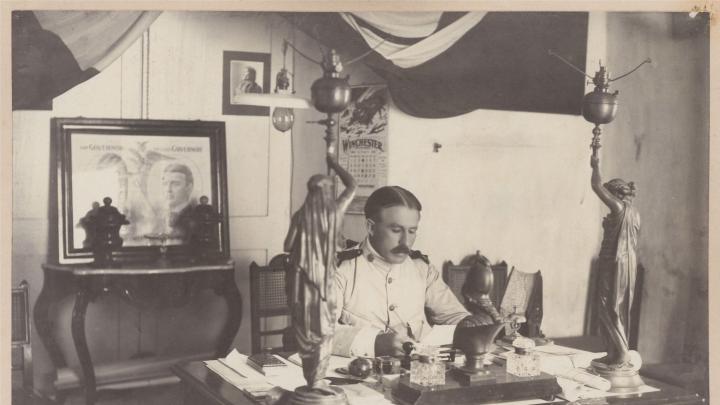

That makes Occupied Cuba, 1898-1902 an even more pertinent, and disorienting, mirror to history. The exhibition (on display in Pusey Library through December 31) is drawn from the rich holdings of the Theodore Roosevelt Collection, which extend beyond the Great Man himself, notes curator Heather Cole. It tells multiple stories succinctly. The first, as captured by photographer Dwight L. Elmendorf, who embedded with the Rough Riders in Tampa and traveled to the island, documents the U.S. intervention in Cuba’s war of independence, resulting in the Spanish-American War in 1898 and the end of Cuba’s subservience to Spain. The second demonstrates the colony’s impoverished state as the Americans found it, in the wake of the revolutionary uprising of 1868 to 1878; the continuing exodus of Cubans from their homeland; Spain’s exactions and post-1878 war taxation; and its efforts to suppress uprisings by depopulating the countryside and relocating people to urban camps. The third, largely recorded by L. Lamarque, shows Rough Riders commander Leonard Wood, M.D. 1884, as enlightened and uplifting in his next role as governor of the eastern province of Santiago de Cuba, in 1898 (he then became military governor of the entire island from 1899 through the declaration of Cuban independence in 1902).

Some skepticism is warranted. Houghton Library staff member Susan Wyssen, who catalogued the collection’s thousands of images and selected those on display, notes their “paternalistic” tone. The photographs of ordinary Cubans tend toward the downtrodden, not the indigenous elite or upper-class Spaniards: local color that justified the military intervention. More broadly, Wyssen says, “This is the story as told by the occupiers, not by the Cubans themselves.” The Cubans, colonial underlings and then liberated subjects of an occupation, had limited means to tell their history during a riven century.

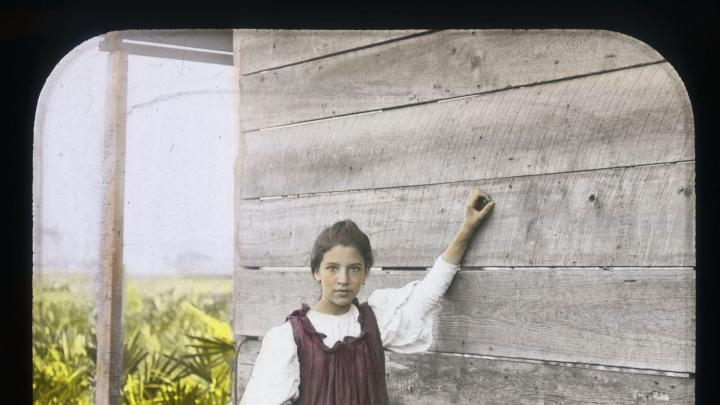

Nowhere are the victors’ assumptions more clearly revealed than in hand-colored lantern slides of Cuban expatriate volunteers shown wading ashore during the U.S. assault (above). Those in their own clothes are unretouched, but their peers who wear U.S. cavalry tops are rendered—shockingly, to modern eyes—as whites. That, too, was part of the narrative in Jim Crow-era America.