There may not be another radio station in America that would air a show like the one WHRB (95.3 FM) broadcast in February of 2013: an hour and a half of music with no song longer than one minute. “It was the most stressful 90 minutes of my life,” says Peter Menz ’15, a former rock director for the Record Hospital department at Harvard’s WHRB, who produced and deejayed the broadcast. “A minute can seem like a very long time. This was not one of those times. I had pulled 80 or 90 songs, and played 60 or 65”: a torrent of music, with barely time in between to announce titles and segue to the next tune. “At the station, people subject themselves to ridiculous dares,” he says. “Like this one.”

Even more amazing, perhaps: many of the brief songs were musically complex works. “The station has always been serious about radio,” says David Elliott ’64, chairman of WHRB’s board of trustees since 1996 and an anchoring presence at the station for 50 years. “It is not a ‘college radio station,’ but a radio station run by college students, who knew from the very beginning that it takes only a second to change the channel. They had to compete on the air with their professional counterparts.”

Indeed, the station that began in 1940 with a signal carried by the electrical system in Harvard’s dorms has evolved into a 24/7 radio presence that matches the reach of the Greater Boston’s commercial stations. WHRB beams music, news, and sports from a tower atop One Financial Center in Boston to an audience roughly circumscribed by Route 495, a beltway about 30 miles from downtown. In an average year, about 150 DJs sit at its microphones in a warren of studios in the basement of Pennypacker Hall.

WHRB's Bruce Morton ’52 interviews freshman Henry Lorrin Lau ’54 of Hawaii.

Photograph courtesy of Harvard University Archives

This fall, WHRB celebrates its seventy-fifth birthday on October 2-4, bringing together many of its 3,000 alumni, known as “ghosts” in the station’s lingo. There will be a reunion banquet, ghost panel discussions, and audio and video presentations. Although WHRB is staffed and run by students, ghosts sit on its board, help the station financially, and contribute expertise to its operations. Trustee Bill Malone ’58, for example, is a broadcast-law expert who, as an undergraduate, helped shepherd the station’s application for an FM license through the Federal Communications Commission. Trustee Marie Breaux Epstein ’90, an accountant, watches over business procedures. Richard Levy ’58 and trustee Robert Landry ’79 are professional broadcast engineers living in the Boston area who provide invaluable help with technical problems, including the rare emergency fix-it call.

Some would argue that WHRB is the best classical-music radio station in the United States: an audacious, if untestable, claim. But WHRB (“whirrb” to fans) airs nearly 70 hours a week of classical music, and does certain things no other station does. In the “real world,” nearly all “CM” (WHRB shorthand for “classical music”) stations deploy a rather limited playlist. Most selections are “warhorses”—familiar compositions like Beethoven’s Fifth or Ninth Symphonies, Tchaikovsky’s Piano Concerto No. 1, or Mozart’s “Jupiter” Symphony. “Warhorses are fun,” says Louise Eisenach ’16, a former co-director of the CM department. “These pieces are famous for a reason.” Yet listeners rarely hear them on WHRB except as part of a Warhorse Orgy during one of its famous “Orgy®” periods.

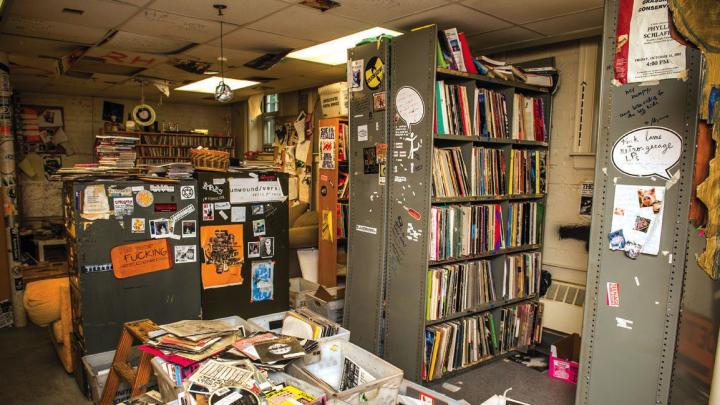

“What makes us great is our extensive library,” notes Eisenach, “and our rule that we never play the same piece of CM twice in one academic year.” WHRB’s catalog contains 49,000 CM items (80 percent on CDs); the station also draws on Harvard’s vast Loeb Music Library, and thus can cue up just about any recording of anything. It doesn’t even air consecutive pieces from the same historical era, so there is no “Baroque Hour,” only shows like Afternoon Concert or Special Concert, plus thematic programs dedicated to the Cleveland Orchestra, say, or the British Choral Tradition. For sheer diversity and depth of repertoire, WHRB is unrivaled.

The same ethos also enlivens the jazz department as well as shows called The Darker Side (soul, hip hop, R&B), and The Record Hospital (known as “RH,” which doesn’t treat ailing vinyl discs, but airs punk and its indie successors). “We try to play things that will surprise people,” says Menz. “People can open up Spotify, Pandora, iTunes, or YouTube and play whatever song they want at that moment. So you have to keep them engaged by playing stuff they’ve never heard before. Someone like Kurt Cobain is a punk warhorse. In the RH lounge, you might see a sticker on his records that says, ‘do not play this.’

“Sometimes I play stuff that is so weird that either [listeners] turn off the radio immediately, or find that they can’t turn it off,” Menz continues. “We have some compilations that are really out there. There’s a CD called Incredibly Strange Music, for example, with a track by a Swedish Elvis impersonator who sounds nothing like Elvis Presley: he slurs all his words and has a thick Swedish accent. If you heard it on the radio with no context, you’d think you were in a demented fun house.”

The orgy tradition, another hallmark, began in the 1940s with Harold van Ummersen ’44, A.M. ’48. Exhilarated after having nailed some “major academic accomplishment, like turning in his thesis or finishing exams,” says Elliott, he dashed over to the studio and celebrated by playing all nine of Beethoven’s symphonies, rounding up a passel of 78 rpm discs and some help for the party. Orgies have become a staple of Harvard exam periods, when students can use some good listening while they study.

Orgies now embrace a wide range of nonstop broadcasts spread over hours or days and organized around composers, performers, periods, whimsical themes, or almost anything else in classical and popular music, from a weekend devoted to the viola to an orgy musically recalling the court of Catherine the Great. In the winter of 1985, Michael Rosenberg ’85 made WHRB the first station anywhere to air the complete works of J.S. Bach, in a nine-day, round-the-clock orgy that celebrated the tercentenary of the great composer’s birth. The station, says Elliott, “has done all kinds of composers complete, from the traditional greats to moderns such as Schnittke and Ligeti.” The winter 2013 orgy period included celebrations of Cuban House (a genre of electronic/house music), jump blues, jazz guitar, and a festival of music from the Tremé neighborhood of New Orleans—all within its first week. Fans can be highly enthusiastic: in 1998, Elliott recalls, a Canadian couple drove to Boston and checked into a hotel for three days just to hear an orgy devoted to pianist Sviatoslav Richter.

In 1948, Dwight Benton Minnich ’51 (“Pappy Ben” on air) launched Barn Howl on WHRV (the AM predecessor of WHRB-FM), feeding the appetite for country music shared by many Southern World War II veterans at Harvard. His early effort evolved into the longest-running, most highly regarded country/bluegrass program on Boston radio, Hillbilly at Harvard, a Saturday morning fixturenowhosted by Lynn Joiner ’61 (“Cousin Lynn”).

Joiner arrived at WHRB as folk music was taking off in 1959 and came to host the weekly Balladeers program—one night featuring a local teenager named Joan Baez. “We may have been the first to air her,” he says. Typifying the playlist, he says, are artists like “the Stanley Brothers [a bluegrass group, floruit 1946-66] and George Jones, the greatest singer in the history of country music,” Joiner adds, “with the possible exception of Hank Williams.” Joiner co-hosted with Brian Sinclair ’62 (“Ol’ Sinc”) from 1976 until Sinclair’s death in 2002. Their formula was one bluegrass, old-timey, or Cajun cut for every two country numbers. “Now it’s just me,” Joiner says.

![]()

![]()

WHRB members in action during the 1950s

Photographs courtesy of Harvard University Archives

He has carried on with gusto plus input from a loyal, knowledgeable audience. Hillbilly promotes local concerts and often brings in musicians for live interviews and performances. Joiner plays contemporary country artists, but doesn’t do “pop country” with its lush arrangements, sticking to the fiddles rather than the violins. In 2014, the International Bluegrass Music Association gave Hillbilly its Distinguished Achievement Award, its highest honor outside Hall of Fame induction.

WHRB began streaming its programs in 1999, connecting the station with a global audience—and now with a local one: as Menz notes, “I’d be hard pressed to find a current Harvard student with a radio in his room.” Online, the station’s newly refurbished website “allows us to post more Harvard-specific content,” explains Martin Kiik ’15, a recent WHRB general manager, “and also to communicate in a medium that college students can conveniently access—and do! The focus is the music, but our DJs have an opportunity to write something insightful about the music on the website—to tell a story about how they found this artist, and how this piece might relate to the rest of the genre.” (The site’s Spinitron listing gives the full names, composers, and artists for every cut “spun,” together with its airtime, and even enables clicking to buy the recording.)

Jazz and many other forms of popular music have always been part of the station. The Jazz Spectrum, broadcast in the contrarian slot of 5 a.m. to 1 p.m. weekdays, has long offered sophisticated programming as a refreshing alternative for commuters on the “morning drive” shift. From 10 p.m. until 5 a.m., The Record Hospital’s DJs expose listeners to “the latest in punk, hardcore, emo, noise, psych, new wave, no wave, post-punk, garage, indie, crust, and whatever else we can damn well get our hands on,” as their Web page announces. On Friday nights, local bands play live on air.

Regardless of genre, WHRB’s underlying musical mission is to uncover fresh, high-quality material—and to share such discoveries with its audience. Undergraduate membership renews steadily; everyone who completes the comp gets on. Many compers bring an impressive store of knowledge with them—RH’s Sam Wolk ’17, for example, had done significant work at commercial radio stations in Los Angeles before college—which keeps the mix musically erudite and percolating. Elliott hosts occasional CM programs as well as one on opera singers of the past that follows the station’s live Metropolitan Opera transmissions on Saturday afternoons.

“The people who’ve come to the station have gained an appreciation of what a radio program is and can be,” Elliott says. “It’s a special presentation of words and music. It isn’t about using focus groups to figure out ‘what people like’ and checking the ratings every 15 minutes. You try to discover the really great music for yourself, and your discoveries will be the listeners’ discoveries—and they will love you for it.”