When Eleanor Elkins Widener witnessed the grand opening of a library that she funded to memorialize her son in 1915, she could hardly have imagined that a hundred years later, the austere building would throw its doors wide open for visitors who came celebrating its anniversary by taking selfies with Harry Elkins Widener’s portrait, nibbling at multi-colored cupcakes, and touring parts of the library that are usually “staff-only”—all accompanied by a jazz band who played outside the main reading room.

The flagship of Harvard libraries and the most prominent building in Harvard Yard, Widener has inspired generations of students and scholars who hold fond memories of a place that allowed them to absorb and produce knowledge in an environment like no other.

When Gurney professor of English literature and professor of comparative literature James Engell first walked up the flight of stairs that led into the imposing library as an undergraduate in the 1970s, his legs were “literally trembling a little.” In the ensuing decades, the library became a “home” for him, a place where most of his work as a student and a faculty member was done. “I probably feel more at home in Widener than any other place in the University,” he said. “I’d say that it’s very close to the raison d’etre of the entire institution.” In Widener, Engell found what he misses the most in an era of constant technology-enabled distractions: a solitary space for quiet study. It is an atmosphere that encourages “slow concentrated thought,” the kind of thinking that is crucial for criticism and judgment but we are increasingly in danger of losing, he said.

For Lane professor of the classics Richard Thomas, the comprehensive collection held by Widener Library was a large part of what attracted him to teach at Harvard. “In those days it mattered to be at an institution like Harvard,” he said. “If you weren’t, it meant you couldn’t get access to the collections.” Thomas conducts research in his private study on the fifth level of the stacks. To obtain the right to use a study like this, new faculty members have the opportunity to sign up for a wait-list. The wait is typically a few years long.

One of Widener’s most appealing features is the serendipity of discovery allowed by its open-stack system. One can encounter pleasant surprises and new fields of knowledge simply by aimlessly wandering through its 57 miles of shelves spread across 10 levels of stacks that hold up one of the largest open-stack libraries in the world. “I’d just encourage people to see the library as an open-ended experience that would repay the curiosity that’s invested in it,” Engell said.

Widener Library’s storied past has been translated into various myths that today’s tour guides use regularly to regale visitors: when Eleanor Widener signed the agreement to fund the library’s construction, the story goes, the grieving mother stipulated that every student must pass a swim test (Harry drowned when the Titanic sank), and every dining hall must serve ice cream (Harry’s favorite dessert). In reality, the Deed of Trust made no mention anywhere of ice cream or swim tests. There was, however, a clause saying that Harvard cannot alter the exterior of the building, which has been honored to this day (though the interior of the building has been dramatically renovated).

If there is a theme to Widener’s 100-year-long history, it would be “opening up”: the past century has seen a continued increase in the accessibility and navigability of its wealth of resources. For Engell, Widener is not only a place, but also an idea: the idea of collecting, preserving, and making available as many materials as possible for its users. Toward this end, the library has made significant progress throughout the century.

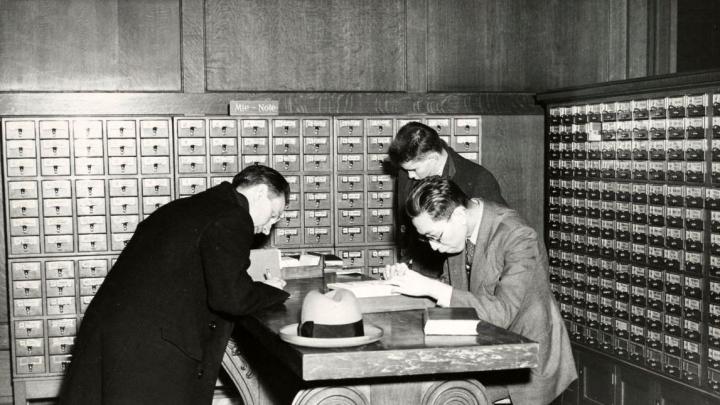

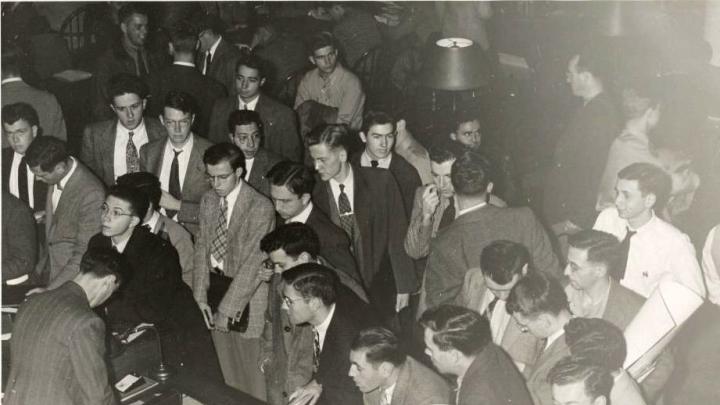

When Widener was first opened, its stacks were not accessible to most undergraduates. Staff members fetched books upon request. The resulting long lines at peak hours made the library especially user-unfriendly. “The librarian's passion for order has helped make Widener an uncongenial colossus devoid of all human warmth,” decried a 1937 Crimson article.

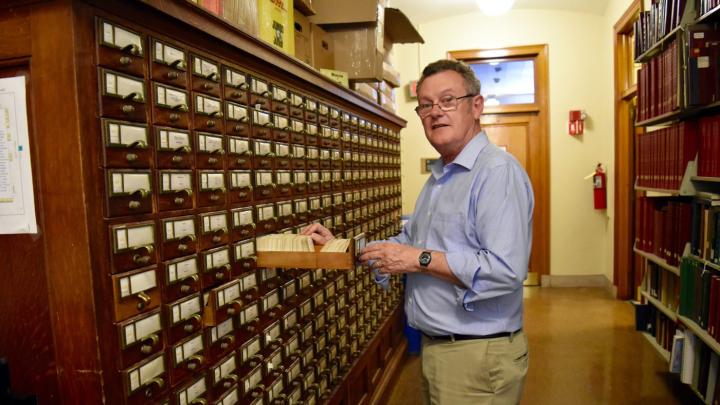

This state of affairs first changed when more general access to the stacks by undergraduates was allowed beginning in the late 1960s. But locating a book still required a manual search through massive catalogues to copy down a book’s call number. The library’s head of services for academic programs Laura Blake, who has worked in Widener for 25 years, said her job used to be much more physically active than it is today: librarians spent a lot of time walking around the stacks, and the phone rang all the time with people requesting simple information that today can be easily obtained online.

The implementation of HOLLIS (Harvard Online Library Information System) during the latter half of the 1980s, along with its subsequent improvements, was nothing short of a game changer, reducing manyfold the time and sweat required to locate resources in the labyrinthine Widener stacks. Today, technology in the library has been taken to a whole new level with a state-of-the-art Conservation Lab and digital imaging facilities that improve the preservation and accessibility of materials as never before.

The presence of female readers in what had been a male-dominated intellectual sanctum was also a relatively new phenomenon in the library’s long history. Undergraduate women’s permitted footprint in Widener was until 1949 restricted to a Radcliffe Reading Room that was barely large enough for a single table—located where today’s public elevator is—and female graduate students who could use the main reading room were not allowed to sit down. All women, patrons and staff, had to leave the building by six o’clock in the evening, according to Widener: Biography of A Library by Matthew Battles. Sarah Thomas, Vice President for the Harvard Library, said that a librarian in the 1950s once got a complaint: “There was a woman here and she sat down!”

Today, Widener extends its welcome to all members of the Harvard community, as well as visiting scholars from outside the University. Each day, an average of 1,715 people enter the library, checking out 2,811 books. Consistent with the theme of “opening up,” the library is constantly innovating as it seeks ways to connect its collections with its readership. Looking ahead, Sarah Thomas said that her strategy for Widener is to reach out to the community and increase people’s awareness of the library’s resources, which include both the collections and the expertise of the librarians.

Next fall, Widener’s hours will be extended to midnight on Monday through Thursday instead of the current 10 p.m., according to Sarah Thomas. Moreover, from 9 p.m. to midnight on Mondays and Tuesdays, the Loker reading room will be used as the venue for office hours of Harvard’s largest class, Computer Science 50: “Introduction to Computer Science I” (CS 50). With its spectacle-filled lectures, festival-like project fairs, and typically rowdy office hours, CS50 seems to stand for everything that Widener is not. Nonetheless, Thomas said she feels “very positive” about having CS50 in Widener’s halls, because it is an opportunity to make students comfortable about working in a library that they may not enter otherwise. Head of services for academic programs Laura Blake said that, in her view, one of the barriers that may dissuade students from using Widener extensively is the library’s “magnificent façade”, as this physical grandeur can be both inspiring and intimidating. “One of my jobs is to be the welcoming presence here and help students get over that intimidation factor,” she said.

Like most libraries today, Widener’s principal challenge in its next century will be to stay relevant in a digital age where e-books are replacing paperbacks and Google searches are replacing treks to the stacks. Forming connections with tech-savvy CS50 students is an attempt to bridge a potential disconnect between a hundred-year-old library with brand new technologies. While the exterior of Widener will remain unchanged, the library will need to constantly adapt and innovate inside its walls in order to engage a 21st century readership.