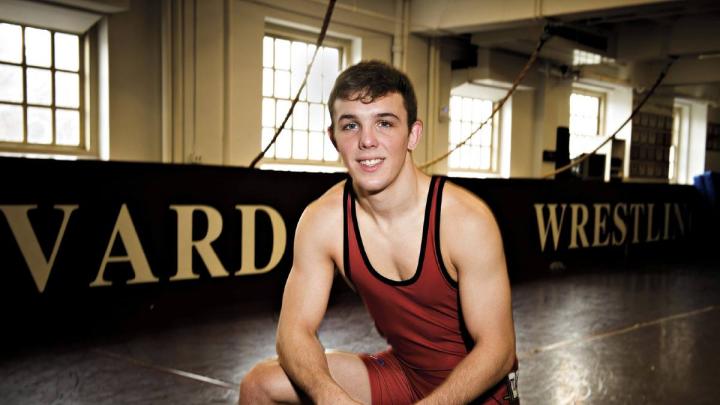

The three periods of a collegiate wrestling match—three minutes, followed by two more of two minutes each—can tick by quickly. “But [comparing it to] a seven-minute sprint doesn’t do it justice. You’re not just using your legs; you’re using your arms, you’re using your head,” says Todd Preston ’16, who wrestles for Harvard at 141 pounds. Meanwhile, an opponent is putting pressure on your head and shoulders, and trying to bring you down to the mat. “You’re battling a lot of adversity in a wrestling match,” Preston explains, “and you have to be mentally strong.”

In the final match of the Eastern Intercollegiate Wrestling Association (EIWA) championships last spring, it took that kind of mental strength for Preston to push past those seven minutes of regulation combat. First, he forced the match into overtime in the final seconds of the third period with a takedown of Luke Vaith, a nationally ranked senior from Hofstra. Then, with barely five seconds left in the second round of sudden-death overtime (first to score points wins), Preston made a buzzer-beating move. As Vaith reached under for his leg, Preston spun out behind and around him, scoring the points that instantly ended the match. That two-point victory earned him the EIWA title and an award as the tourney’s Most Outstanding Wrestler. “It’s just what our coaches always told us when we were little kids,” he reflects. “You can’t stop wrestling until the whistle’s blown.”

Coaches have always called him a “scrappy” wrestler. “I’m always moving everywhere,” Preston explains. “Someone described it like this to me: I’m like a little kid trying to play with an older brother, and I’m slapping him across the face, running in circles.” A more technical way to describe Preston’s wrestling style might be what he calls “flow.” “I get a shot, he blocks, and I’m immediately going to the other side” and attacking again, even before regaining full balance, he explains. “It’s just constantly moving, and constantly threatening and attacking.”

Relentless offense enables a wrestler to score points in each of wrestling’s three positions. Wrestlers begin the first period of a match standing apart in the “neutral position,” from which each tries to take the other down to the mat. In the next two periods, wrestlers take turns choosing among the three positions—neutral again, or top or bottom. (The wrestler who crouches below the other is in the “bottom” position.)

Preston always chooses bottom, knowing he has the strength, and the technique, to escape. He wins one point for the escape—returning to the neutral position—and a second if he can manage to place his opponent below him, scoring a “reversal.” To escape, Preston focuses on preventing his opponent from putting too much pressure on his head and shoulders, and on getting his weight back over his hips. This makes him less vulnerable to flipping and better able to use his leg muscles to pivot and stand. Preston calls bottom a “mental game,” because it often takes several attempts, and getting knocked back down to his knees several times, before escaping. “It’s almost a metaphor for life,” he says, but adds, “I’m very confident that I can get out. It’s like a guaranteed point.”

Preston began developing his aggressive style at the age of five, as his father, Robert, who had wrestled through high school, introduced both of his sons—Todd and Robbie, eight years older—to the sport. Growing up in Hampton, New Jersey, Todd wrestled with youth clubs and then at Blair Academy, where he earned three national prep-school titles. As captain, he led Blair to a first-place national ranking his senior year. After a call from Harvard coach Jay Weiss, he followed his brother to Cambridge (where Robbie ’07 reached the NCAA tournament three times, at 125 and 133 pounds).

Despite these early successes, it took a tough freshman year for Preston to bring together his mental and physical game. In tournaments, teams can enter only one competitor in each weight class, and Harvard already had a superstar at 141 pounds—then-senior Steven Keith ’13. As Preston faced the choice between losing crucial mat time and facing much bigger competition at 149 pounds, a bout of appendicitis in late October interrupted his season. He returned to the mat in January and wrestled “up” at 149, getting the feel of collegiate wrestling but taking real drubbings. “Even though I might get my butt kicked wrestling big guys,” Preston says, “I was getting better conditioning, I was getting stronger, I was getting better technique.”

Those challenges taught him to push away anxieties and focus on the task at hand, setting him up for success sophomore year. “He’s one of the most talented wrestlers I’ve ever coached,” Weiss says. “[But] that’s only part of our game. There are too many guys I’ve seen work so hard and just not have the mental game. Last year, he put it together.”

One big area Preston worked on last year, and continues to attack this year in practice, is learning to score more points when wrestling “from the top.” (The opponent, after all, may choose that bottom position Preston prefers.) In the NCAA quarterfinals last spring, he learned how it feels to wrestle an opponent who excels in the top position. After losing to Logan Stieber, the Ohio State wrestler who went on to win the national title, “I thought I needed surgery on my shoulder,” Preston says. “But everything was legal. This sounds so messed up, but I would love to put my opponent in that much pain and be able to score.”

This season, he returns as one of two team captains on a relatively young Crimson squad, ready to make good on the promise he saw in his performance last year. Because he lost by a single point in the NCAA tournament’s Round of 12, he fell just short of earning All-American status, awarded only to the top eight finishers. This year, Preston is balancing his signature mental style—focusing on the moment, not the season—with his longer-term goals. “I was one point away,” he says, “but that just fuels the fire for this year.”