Abundant light and glass will greet visitors when the Harvard Art Museums reopen at 32 Quincy Street on November 16. The centrally located Calderwood Courtyard now rises through five stories to a glass roof. Natural light from this “lantern” suffuses the space and blends with artificial lighting installed in the farther reaches of the building. This is a trademark of architect Renzo Piano, designer of the Menil Collection in Houston, the Paul Klee Center in Bern, Switzerland, the renovation of the Morgan Library in New York City, and the expansions of the Art Institute of Chicago and the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston, among others. Piano refers to the roof as “a light machine.” But the renewal of 32 Quincy Street’s functions as a building—which also include modern necessities such as climate control and improved security—are matched by the museums’ equally evident rededication to a purpose.

Teaching, it rapidly becomes clear, is what drives the program and many of the design decisions in the 2o5,000-square foot building. “We have some of the greatest collections in the country,” says Cabot director of the Harvard Art Museums Thomas W. Lentz. “We desperately needed to make them far more accessible…and we wanted to put them to work for all students, all disciplines, all faculty, because we have a deep belief in the power of works of art to teach in very different ways.” Harvard, he points out, is “the birthplace of art history as a discipline, as well as art conservation and conservation science.” (Harvard’s virtuosity in that latter discipline is on display in a special Rothko exhibit that uses light to restore badly faded pigments; see harvardmag.com/rothko-14.) To that end, the building houses new study centers where students, scholars, and the public can, under supervision, have up-close experiences with works of art; the Straus Center for Conservation and Technical Studies, visible through glass walls on the same floor; and “University galleries” dedicated to the display of artworks installed specifically for College courses in the history of art and architecture, interdisciplinary General Education courses, or any other course bearing on museum holdings. Even the curation of the permanent collections has come to reflect art history as it is now taught. American art, for example, is no longer considered separate from the European art-historical tradition.

This has led to thought-provoking reinterpretations. The gallery that might once have been labeled “American” now reflects the transatlantic exchanges of European currency, images, and ideas with colonial and Native American culture. Copley portraits of Boston merchant princes clad in Turkish garb hang opposite portraits of Native Americans (drawn, explains Winthrop associate curator of American art Ethan Lasser, by a painter sent by the French government to render their likenesses). A Charles Willson Peale portrait of George Washington that was sent to Paris hangs near one of Benjamin Franklin, then in Paris representing American interests, portrayed by the French painter Joseph Duplessis. In the center of the room is a wrist ornament made of wampum, loaned (like the images of the Native Americans) by the Peabody Museum—a sign of increasing cooperation among University collections. Of the wampum and a nearby piece of British silver, Lasser says, “There are some similarities”: both are aesthetic art materials and materials of exchange. “Silver is money, but here it is also a bowl. Wampum is a kind of currency, but it is also a jewel.” And the wrist ornament depends on trade, “because the drills used to hollow the interior of the wampum beads were steel drills that Native Americans traded for.”

The cultural exchange illustrated in the American gallery is emblematic of the way art is considered throughout the museum, and was made possible by two major changes. First, the museums’ 10 tiny curatorial departments were combined into three larger divisions—Asian and Mediterranean; European and American; and Modern and Contemporary—to facilitate scholarly exchanges. Second, the new building has brought the three separate collections—the Fogg, the Busch-Reisinger, and the Arthur M. Sackler museums—together in one location so that, as Lentz describes it, “they can finally begin talking to one another. We can now begin to establish the multiple visual, intellectual, and historical linkages among these collections.”

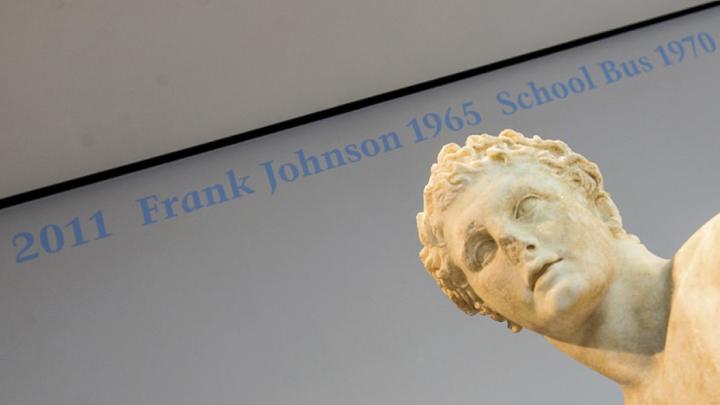

Thus sculptures by Auguste Rodin and Louise Bourgeois are woven into a display of Roman sculpture organized around themes of dynamism, the human body, and materials. A spirit of experimentation, even playfulness, characterizes some of the newly installed galleries. High on the wall above the Roman sculptures, a word portrait by Félix González-Torres acts like a frieze. “I was very excited about this guest, as it were,” says Hanfmann curator of ancient art Susanne Ebbinghaus. “Word portraits are actually something that we have a lot of in the ancient world. Think of the deeds of Augustus or inscriptions in the palaces of Assyrian kings.” Because “the frieze is an element that is derived from classical architecture, I thought [it] would fit very well and chime in very interesting ways with the ancient works of art displayed, but open them up to the twenty-first century.”

In an adjacent gallery of Greek vases, the installation reflects how these ceremonial objects would have been seen when used. A krater for mixing wine and water, its decorations depicting Dionysus and a procession of misbehaving satyrs, has been “consciously placed at the center of the gallery, just as it would have been placed at the center of the ancient Greek drinking party,” Ebbinghaus says. A nearby case displays drinking bowls on their sides, as they would have been seen when raised to the lips, revealing the interior design visible to the drinker. The display also shows the bottom of the cup when raised, “what your companions see as you are drinking,” she continues. “It shows you how these objects actually would look in motion”—a suggestion of what “people can really experience a little bit in the study center,” where these ancient objects may be handled.

On the fifth floor, one up from the study centers, the so-called lightbox gallery offers visitors the opportunity to explore the museum’s collections digitally. A project of Harvard’s metaLAB in collaboration with the museum, the space will allow visitors to interact with images of artworks and their associated data (date of acquisition, artist, colors, technique, style, or other attributes). Museum collections are becoming “visible through websites,” says metaLAB co-director Jeffrey Schnapp, presenting “a world of opportunities for thinking about programming, research, communication, engagement with local and off-site communities, and for enhancing, altering, or expanding the compass of what a visit is—even the on-site visit.” The system will let visitors explore objects on display more deeply, and eventually even collections that aren’t on display. “It’s a nimble space,” says Schnapp, a professor of Romance languages and literatures who also teaches at the Graduate School of Design. The system could even be used to teach students about curatorial work, allowing them to “assemble objects and make arguments with them.”

Students are central to the “reoriented compass” of the museums, says chief curator Deborah Martin Kao. “If we can do something that is at the right pitch to [generate] excitement and curiosity in an undergraduate,” she recalls thinking, “then we will have gotten it right for most of our other audiences.” As planning for reinstallation of the galleries got under way, “We began to realize that, even in the permanent collections, the time and research and level of thinking” going into that process were commensurate with the effort required to stage a special exhibition. “To meet the aspiration that we were setting for ourselves”—the creation of an “incredibly robust teaching platform”—“we needed the galleries to do something more than they had in the past.”

That meant, as well, the commitment of a large space to the University galleries that would be programmed in consultation with faculty members for specific object-based teaching in their classes; creation of on-site storage to enable nimble supply of artworks to the study centers; allocation of space to a materials lab for studying artmaking; and a commitment by curators as they pursue their own scholarly projects to involve faculty partners, undergraduate and graduate interns, and fellows in their work, Kao says.

In addition, reports director of academic and public programs Jessica Levin Martinez ’95, the museum now has a 19-member undergraduate and graduate-student advisory board and an undergraduate guide program. Students from the Harvard Graduate School of Education, meanwhile, are working in the galleries with Cambridge Rindge and Latin School students. There are also plans to explore how the museum could be used in “flipped classrooms,” in which lectures are viewed online and the participatory work takes place in one of the museum’s galleries or study centers.

One of the effects of the museums’ renewed focus on teaching has been to enhance the way its paper collections are deployed. Of the 250,000 objects held by Harvard’s three art museums, four-fifths are works on paper. These are often particularly useful in teaching, but also susceptible to light damage. As curators imagined how these collections could best be utilized in teaching, Kao says, they tried to open themselves to the idea that works on paper could drive the argument in a gallery. A modern gallery focused on the 1960s, for example, is anchored by “two deep and important paper collections:” Joseph Beuy’s Multiples and a Fluxus movement collection. “The two speak to each other,” says Kao, “because they both deal with the issue of the multiple, a key concept for the art of the 1960s. We built the rest of the gallery around them.” This, together with a systematic program for rotating works on paper into display, will allow more of these valuable teaching objects to be shown.

Kao says that part of what allows the new museum to fashion itself as a teaching machine is its position in the larger ecology of Greater Boston art museums: “Unlike the Yale University Art Museum, which is the only game in town in New Haven, we don’t have that pressure.” The “magisterial American wing of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston tells the story of America in a monumental way. [Salem’s] Peabody-Essex Museum lets visitors understand the seafaring, Silk Road story in a powerful way.” Harking back to the museum’s innovative American gallery, she continues, “We felt the privilege of being in Boston” made it possible “to tell this other, integrated story—of the colonial Atlantic as a collision of world-views that gets played out in a kind of visual economics.” She concludes, “We can’t wait to unleash the capacity of this new building to really move the field forward.”