Furtiveness, denial, and pugnacious, abrasive families permeate the dark stories of Jean McGarry ’70. The Providence, Rhode Island, native has set down an unblinking account of the blue-collar Irish of that state. “It’s a clannish culture,” she says—and one that likes to turn inward on itself, not outward. After reading her first short-story collection, Airs of Providence (1985), her parents were furious. “You know, Jean, we keep our secrets,” raged her father, Frank.

Indeed they do. “When we turned the lights on in our house, we would rush to pull down the blinds so people couldn’t see in,” McGarry says. “There was a terror of being observed. Whatever was inside the house was supposed to be perfect—though actually it was a shambles. The houses were a mess, physically and otherwise. One thing I’ve written about is what goes on inside the house.”

For example, this, from “And the Little One Said,” published last year in The Yale Review: “Dad died of the usual causes: drinking, heart trouble, diabetes, cancer, and the war, where—although a supply sergeant—he lost an eye and his left thumb. He wouldn’t talk about it, so there had to be a story and no glory, as we liked to say about anything that went wrong. Not that we said it to his face. He had a bad temper, and kept the strap looped over the kitchen door, and we learned to run like rabbits...the one who really pulled his chain was Mom, but she was a sprinter in school, and first up the stairs and into the bathroom, door locked.”

Soon: “Dad was dead one week, and his old mother living with us, as she’d always wanted to.... She’d left the cemetery early, jumped into a cab and whipped past the Y to get her bag. When we got home, eyes dripping and snotty noses, she was installed, and stirring Ritz crackers into a cup of warm milk…. It was one bully taking over for another in a single day.”

Six of McGarry’s eight books—which include three novels and five short-story collections—have rendered this Rhode Island subculture with merciless realism. (Nearly all the books come from the press at Johns Hopkins, where McGarry is a longtime professor and co-chair of the Writing Seminars.) Though other authors (like John Casey ’61, LL.B. ’65, in his 1989 novel Spartina, winner of the National Book Award) have depicted Rhode Island culture in pitch-perfect detail, McGarry may have painted the most evocative portrait of how the common people live in the nation’s smallest state.

“Even in 1966, at Regis College, a Catholic school [from which McGarry transferred to Harvard], my past felt like I had lived in the Middle Ages,” she says. “At Harvard in the late ’60s, it became the Dark Ages. Nothing I’ve encountered later in life was anything like it, nor would anyone believe such a shtetl-like world existed in the United States as late as mid century.”

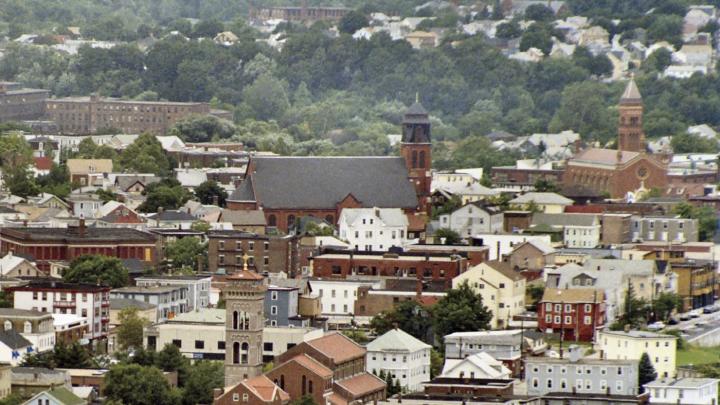

In that world, “natives find no need, for the most part, to leave the state—even to go to Cape Cod,” she explains. “The population, largely Irish and Italian Catholic, dominate everything in a uniquely ward-heeling and who-do-you-know-in-city-hall kind of way. The first five major industries from the early Industrial Age—like Brown & Sharpe, New England Butt—were still there in my lifetime, and my extended family worked in all of them. Generations attended the same Catholic schools, were waked at the same funeral homes, and interred in the same cemeteries.”

The Irish proletariat of McGarry’s tales often feels “demeaned and worthless, yet somewhat proud,” she says. “They are always scanning for the insult.” She recalls that as a child, “I heard so much abuse, it became a kind of music. It’s a really lively language.” There’s abundant drinking in her stories, though it mostly happens offstage, in references to bottles hidden around the house, or the six-pack an older man’s wife brings him each day; the reader can imagine the effects on daily life. Ironclad hierarchies, like those of the church—“Jesuits on top of the heap, Franciscans and Dominicans a few steps below”—organize everything. Even crockery was stratified, with Belleek porcelain from Ireland representing “the Holy Grail, the great prize.” It’s all “a gift for a fiction writer,” the author says. “Fiction needs organized worlds.”

Though so firmly rooted in place, many of McGarry’s characters seem adrift in every other way—in their intimate and family relationships, their emotions, their values and habits, and even, despite the looming presence of the Catholic church, in their spiritual lives. They appear condemned to their rigid, beaten-down patterns, and seem to lack the imagination to conceive an alternative. Even so, their love for each other seeps out through cracks in their souls, expressed indirectly in actions like lovingly tending a gravesite.

Take the quiet story “Providence, 1954: Watch,” which tracks the last hours of a dying man who looks out the window from his bed on a wet Halloween day, still absorbed in dramas like a poignant moment when the rain causes a child’s trick-or-treat bag to give way, dumping his candy on the ground. Around 4:30 in the afternoon he breathes his last, his wife sitting nearby in a rocking chair. The story ends with her thoughts as she watches him in his bed: “There was no room in there for her, but more than she expected, or would ever say or think about again, she wanted to climb in there with him. That was the doorbell, but in an hour or so when it would be so dark you didn’t know who or what you were getting, she was just going to sit and let it ring.”