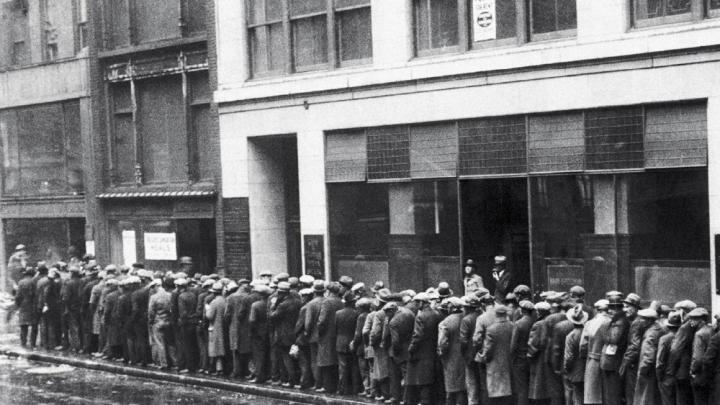

In the early 1930s, as a stock market crash spiraled into the Great Depression, the governors of the Federal Reserve frequently declined to provide emergency loans to banks, instead standing by as they failed. The prevailing economic orthodoxy held that painful as an economic downturn might be, it served to purge weak banks and other businesses. If they were protected, inefficiencies would be preserved—to the long-term detriment of the economy.

Most economists now believe that this approach—combined with the high interest rates needed to maintain the gold standard—contributed significantly to the depth and severity of the Great Depression. “There’s a broad consensus” that the Fed’s policy back then “was a terrible mistake,” says McLean professor of business administration David A. Moss.

This understanding arose from academic research conducted in the second half of the twentieth century. Economic modeling and study of the actual events enabled economists to say with a high degree of confidence that the misery inflicted during the Great Depression could have been tempered significantly with different monetary policy. Comparative studies strengthened the conclusion: the countries that got off the gold standard quickly and pumped money into their economies (as the Fed declined to do) recovered from the depression faster.

When a new financial crisis began to take shape in late 2007, then-Fed chairman Ben S. Bernanke ’75 “had that research in his back pocket,” says Moss. In fact, Bernanke, an academic economist, had contributed to this literature himself. As a result, the central bank’s response in 2008 was altogether different from its response in the early 1930s: this time, it pumped funds into the financial system, bringing short-term interest rates nearly to zero to support banks and stimulate the economy. Though the efficacy of continuing that policy today is debated, Bernanke’s actions “may well have helped prevent another Great Depression,” says Moss, “and it was at least in part because sound research shaped his thinking about monetary policy in a crisis.”

This exercise in retrospection in fact informs much of Moss’s work. It illustrates the huge stakes for people’s lives implicit in large questions that can be engaged by social science; the capacity to answer those questions better with better social science; and the value of evidence and deep, methodical, empirical scholarship. “When people think about transformative research, they tend to think of the natural sciences,” Moss says. “I believe social-science research can also be—and has been—transformative. So how do we increase the likelihood of that happening?” The answer to that question is embedded in the Tobin Project, an independent, nonprofit research organization he founded in 2005.

Asking the Right Questions

The animating principle underlying the Tobin Project grew from conversations between Moss, then a graduate student, and his mentor, the late Yale economist and Nobel laureate James Tobin ’39, Ph.D. ’47, JF ’50, LL.D. ’95. They often discussed an idea that Tobin laid out in an autobiographical essay:

[E]conomic knowledge advances when striking real-world events and issues pose puzzles we have to try to understand and resolve. The most important decisions a scholar makes are what problems to work on. Choosing them just by looking for gaps in the literature is often not very productive and at worst divorces the literature itself from problems that provide more important and productive lines of inquiry. The best economists have taken their subjects from the world around them.

That challenge has translated into the Tobin Project’s mission. (A poster excerpting part of the quotation hangs in the conference room at the organization’s Harvard Square office, signaling to all who enter what the enterprise is about.) Aiming to catalyze significant research, it works to

mobilize, motivate, and support a community of scholars across the social sciences and allied fields seeking to deepen our understanding of significant challenges facing the nation over the long term, and to engage with policymakers at every step in this research process. Toward this end, the Tobin Project aims to identify and pursue questions that if addressed with rigorous, scholarly research could have the greatest potential to benefit society and to unlock doors within the academy to new and vital lines of inquiry.

Doing that work well has come to involve a network of more than 400 scholars affiliated with 80 institutions, pursuing truly interdisciplinary research. “It’s a really amazing model,” says Poorvu family professor of management practice Arthur Segel, one of the organization’s founding board members. “With very little money, we’ve got hundreds of scholars doing research on important issues together.”

Yet that institutional innovation has proved to be far less challenging than the definition of worthwhile queries to pursue: large problems on which social scientists can engage each other productively, make meaningful discoveries, and shape both society and the future of research. Tobin aims high. Moss cites examples of the influence of social science ranging from the origins of Social Security, which was first envisioned by academic economists, to foundational civil-rights advances such as the desegregation of American schools. But identifying such turning points in hindsight turns out to be much easier than framing them prospectively.

At the project’s inception in 2005, Moss and colleagues from across the country convened 12 interdisciplinary groups to address obviously big subjects—energy, the environment, pensions, tax policy, regulation, and so on—assuming, Moss recalls, that “magic would happen.” It did not. “If you ask people to sit around and talk in working groups,” says Moss, “that’s what they’ll do. They’ll talk. Bringing talented people together around a table can be helpful, but it doesn’t necessarily produce research, let alone great research. A weekend meeting of the smartest cancer researchers is not going to cure cancer.” And so the Tobin Project became a learning organization, inventing its own new approach to finding worthy, actionable ideas for research.

In those days, says Moss, “There was a tremendous desire to just do something.” But he recalls Tobin’s first executive director, Mitchell B. Weiss ’99, M.B.A. ’04 (now a senior lecturer at Harvard Business School), saying, “If you don’t have a strategic direction, don’t move.” The new strategy, which Weiss and Moss shepherded, involved constant experimentation to figure out how to inspire research. Moss focused especially on developing strategic questions, while MIT political scientist Stephen Van Evera, the Tobin Project’s national security chair, stressed the importance of building communities of scholars with strong personal relationships. Segel, meanwhile, facilitated connections with policymakers, who helped to ground the work. When Stephanie Khurana, M.B.A.-M.P.P. ’96 (now co-master of Cabot House), joined the team in 2010 as acting executive director, she encouraged Moss to articulate a clear process, breaking it down into steps that other organizations could follow. Thanks in part to these innovations, says Segel, “we’ve created a new research model that takes advantage of all these great research institutions our country has.”

Today, the first (and, some would say, most important) step in any Tobin inquiry is the identification of good questions. That task falls mostly to a small group, including Moss himself and some combination of: an expert scholar or two in a given field, Tobin director of research John Cisternino, J.D. ’08, and a staff member or members, who undertake searching, protracted screening of the literature to develop a work plan. Rather than pursue the original dozen fields, the project currently focuses on four areas:

- government and markets (the conditions for successful regulation of the economy);

- institutions of democracy (the aspects of government, business, and civil society that are central to the functioning of American democracy);

- national security (how the United States can advance its security interests in light of fiscal constraints and changes in the global distribution of power); and, since 2009,

- economic inequality (the consequences of widening income disparities for the U.S. economy, society, and politics).

In each case, Moss says, successful work plans must survive several filters. Would a Tobin-convened inquiry facilitate research that would not be pursued otherwise? Does it concern an important, real problem? Would scholars commit to work on it over time? Would their work inspire wider research? And could answering the question change public debate?

The plan for investigating inequality—among the most contested of contemporary issues, but hardly the best understood—illustrates the full force of this process.

Interrogating Inequality

“People make all sorts of claims every day about inequality,” says Moss. For example, some analysts hold that rising inequality among Americans caused the financial crisis, as the rich invested in additional financial assets like mortgage-backed bonds, enabling those at the bottom to maintain consumption—despite a diminished share of income—by taking on too much unaffordable debt. If true, that suggests urgent action to maintain economic stability. But others dismiss this argument, viewing rising inequality “as little more than a hiccup” or even celebrating it as “a favorable development…in the progress of American capitalism.” Thus Moss, Anant Thaker, M.B.A. ’11 (now of Boston Consulting Group), and Tobin staff member Howard Rudnick summarized the situation in a working paper published last summer. “The problem is, there is no consensus in the research on the consequences of inequality,” says Moss. “We often make policy based on guesses, and this may be necessary at times. But it would be great if we didn’t have to.” “The problem is, there is no consensus in the research on the consequences of inequality,” says Moss.

He knows exactly what gaps exist in interpreting inequality, because the working paper is a sweeping, relentless review of the literature in an attempt to tease out a meaningful approach to understanding the implications of the new reality: that from 1980 to 2010, the income share of the top 1 percent of Americans doubled (to 20 percent), and that of the bottom 90 percent decreased by one-fifth (from 65 percent to 52 percent).

Research around the world on the measurement of inequality is robust and proceeding well, and there is at least a degree of scholarly consensus on the causes of rising inequality, Moss explains. But despite all the work done to date on the societal consequences of greater inequality, scholars have achieved little agreement.

Economic growth? Moss and his coauthors find it “impossible to conclude…that there exists anything even remotely resembling an academic consensus on the relationship between inequality and economic growth.” Health? The “evidence on a causal relationship” between income inequality and the health of the population as a whole “remains anything but clear.” Political outcomes? In theory, greater inequality might be expected to promote greater pressure for redistributive policies—but adoption of such policies could also be thwarted by “asymmetrical political power for the top end of the distribution.” Three decades after the leading theory on inequality as a driver of redistribution in democracies was advanced, “the academic community remains divided regarding both its accuracy and the true nature of the effect (if any) of income inequality on political outcomes.”

Thus, along almost any dimension of analysis important to social-science researchers (involving different theoretical underpinnings, sample selection, data, and methods), they cannot confidently say that they understand or can explain the consequences of greater economic inequality for society as a whole: surely a pressing priority for effective inquiry. “Of course,” says Moss, “given the magnitude of changes in inequality we’ve seen, it seems very likely that there are significant societal effects, which will eventually be found. But it’s ultimately an empirical question, and so far—despite much outstanding work—the large-sample empirical research on consequences remains inconclusive.”

How, then, to proceed? Moss, Thaker, and Rudnick home in on the mechanisms through which inequality may lead to provable consequences for society. In particular, they define an agenda of behavioral experiments that might assess how high or rising inequality affects individual decisionmaking: how changes in inequality in society affect choices about consumption and saving, hours of work, taking risk, or trusting others. In effect, they propose a novel melding of streams of research: testing behavior under varying conditions of inequality.

Tobin’s working group for this new inquiry (Moss describes it as an “academic dream team”) includes scholars who had already begun using experimental methods to examine related questions. Professor of business administration Michael I. Norton has tested people’s perceptions of, and preferences for, the distribution of wealth in society (see “What We Know about Wealth,” November-December 2011, page 12). Columbia University economist Ilyana Kuziemko ’00, Ph.D. ’07, has written with Norton about the concept of “last-place aversion”—the propensity displayed by subjects in laboratory experiments to take greater risks when they are placed at or near the bottom of an imaginary society, apparently because we all object so strongly to occupying (or falling onto) the lowest rung of the societal ladder.

Other participants include professor of business administration Francesca Gino, whose research examines why people don’t stick to decisions they make, among other questions, and Kuziemko’s Columbia colleague Ray Fisman, Ph.D. ’98, whom Moss characterizes as one of the most creative social science researchers he knows, and who has studied everything from racial preferences in dating to cultural differences in corruption (the latter based on United Nations diplomats’ likelihood of paying a parking ticket in New York).

In a second prong of the quest to understand the mechanisms by which inequality operates, another part of the Tobin group is planning experiments to examine inequality’s psychological effects, including on physiological markers of stress. Two psychology professors with expertise in this area from the University of California, San Francisco are taking the lead: Nancy Adler, Ph.D. ’73, who was one of the first to encourage Moss (and to volunteer to help) after hearing about his attempt to connect the fields of inequality and decisionmaking, and Wendy Berry Mendes, who was assistant and then associate professor of psychology at Harvard from 2004 until 2010.

The scholars in the working group combine individual expertise in economics, psychology, history, business, and public policy. Their work is truly interdisciplinary: the scholars learn from one another and adapt their own thinking, instead of just working alongside one another with each one continuing on his or her previous path. “People often say interdisciplinary when they mean multidisciplinary,” says Moss. “But this group is truly interdisciplinary, and it’s such a privilege to work with them.”

He hopes that results from these experiments will produce new ideas for framing experiments out in the world—for instance, about how inequality affects people’s preferences regarding everything from consumer borrowing to investment in public goods, such as schools. “By studying these possible mechanisms at the individual level,” he says, “we may eventually be able to say with some confidence whether inequality actually causes certain societal outcomes”—an achievement that has eluded most inequality researchers.

Wiener professor of social policy Christopher Jencks, who has been conducting influential research on inequality since the 1960s—and who recently revealed he had given up on his own long-term project on the social effects of inequality, for lack of convincing conclusions—has said he believes that the Tobin group’s plans represent the most promising direction in inequality research today. “We don’t know whether rising income inequality in society as a whole affects people’s sense of who they are or who they think they can become,” says Jencks. “Nor do we know whether changes in inequality affect people’s feelings of compassion for those less fortunate than themselves, envy of those more fortunate than themselves, or solidarity with neighbors and fellow citizens.” Where many have speculated, the Tobin group is trying to find answers. Says Jencks, “I think we will be wiser as a result.”

Reframing Regulation

“If residents of an apartment complex witnessed a bitter argument between a father and son just days before the father was murdered, investigators might reasonably be interested in the son as a potential suspect. Yet evidence of the argument, by itself, would hardly be grounds for conviction.”

So write Daniel Carpenter, Freed professor of government, and Moss in their editors’ introduction to Preventing Regulatory Capture: Special Interest Influence and How to Limit It (just published by Cambridge University Press). It is an unexpected analogy in the first part of a huge academic tome—but it conveys some sense of their ability, and intention, to bridge the gap between scholarship and practice, and minimize policy based on guesswork and on inferring causation where it may not exist. And it and the title have a larger purpose: conveying vividly the central discoveries of the Tobin Project’s recent work on government and markets.

That work dates back to the original Tobin Project group on regulation, created in late 2005. Duke University historian Edward Balleisen, who chaired the group at the time, recalls that “prevailing theories on government and business relations (especially regulation) were premised on government failure. We wanted to engage more substantially with instances of regulatory success, and deepen the empirical basis for judgments regarding a range of regulatory strategies: when they achieved their aims and when they didn’t, and how to distinguish the first from the second.” The group’s early efforts culminated in Government and Markets: Toward a New Theory of Regulation, co-edited by Balleisen and Moss, which suggests ways to study the effectiveness of regulation in specific cases, and offers examples of cases where regulation has worked, or hasn’t, in American society.

Even before that volume was published in 2010, the country had succumbed to a major financial crisis, and experts on economic regulation were in demand. Several in the Tobin network—among them Moss, Carpenter, and Elizabeth Warren, then Gottlieb professor of law, now a U.S. senator—found themselves regularly en route to Washington to talk with lawmakers about financial regulatory reform, including the possibility of creating two new agencies focused on consumer financial protection and the management of systemic risk. “At the same time,” recalls Melanie Wachtell Stinnett, then Tobin’s policy director, “members of Congress and the administration raised a new question: how could they design new regulatory agencies that wouldn’t fall prey to ‘regulatory capture’?”—the “capture” of a regulatory agency by those it oversees, resulting in its failure, or corruption.

This real-world question, and the lack of existing scholarship to answer it, gave Moss the focus for the next round of regulation research at the Tobin Project and led to Preventing Regulatory Capture. “Nobody was looking at capture from the perspective of how to prevent it or mitigate it,” says Tobin research director John Cisternino. The organization worked closely with top scholars, he says, to “get the right people involved and ask the question in a way that they could do something powerful with it.”

The research was also powerfully shaped by news late in the last decade. First was a popular narrative about the financial crisis, the Deepwater Horizon explosion and oil spill, and other untoward events. As Carpenter and Moss put it:

Consider a few recent “scandals” in the news: financial regulators missing investment fraud and toxic loans at the very time their staff was shuttling back and forth between Washington and Wall Street; energy regulators ignoring the risk of a catastrophic oil spill just as their inspectors and officials were cavorting with industry managers; a telecommunications regulator making a series of industry-friendly decisions, and just over a year later a prominent commissioner who was a pivotal vote in these decisions departing the agency to take a high-status vice-presidential position with a regulated company.

To all appearances, each incident demonstrates the “capture” of a regulatory agency—and an airtight case for it to be dismantled, or at the least completely overhauled. But as their analogy suggests, “Plausibility…lies quite a distance from proof.”

Second, Moss observes, the very nature of the financial crisis brought to light new needs for “systemic” regulation. When financial institutions obscured the risks of low-quality loans in collateralized mortgage obligations; enmeshed one another in far-reaching credit-default swaps; and simply became too large to fail—some different regulatory regime was clearly needed.

Defining an inquiry into regulatory capture enabled fresh understanding, unmoored from prevailing assumptions. When the scholars set to work, says Carpenter, whose previous research includes an exhaustive history of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, “We needed a precise definition: what do we mean by capture and how do we know it when we see it?” There hadn’t been a book on the concept in 30 years. There was, he says, “an oversupply of theory and an undersupply of data.” “What do we mean by capture?” There was, Daniel Carpenter says, “an oversupply of theory and an undersupply of data.”

In the intersection of these trends—popular distrust of the efficacy of regulation, the new need for such oversight, and a prevailing social-science theory that over-predicted regulatory capture and may have overprescribed wholesale deregulation—the Tobin scholars found an urgent need for fresh, better social science. The new book (one product of that work) combines historical investigations, new theory, and detailed case studies to advance an operational definition of regulatory capture, a taxonomy of the varying forms and degrees of the phenomenon, and, perhaps most important, insights into what Carpenter and Moss call “the conditions under which regulation sometimes succeeds, or can be made to succeed, when capture is constrained.” In other words, the scholars’ research has shown ways to make needed regulation and governance work, so business processes—manufacturing drugs, producing energy, making consumer loans—can operate safely, productively, and fairly.

“Weak capture” (defined as special-interest influence compromising “the capacity of regulation to enhance the public interest, but the public interest is still being served by regulation”) may be nearly ubiquitous. But where some net social benefit remains, so does the case for regulation—perhaps modified, but not abandoned. Resorting to analogy again, Carpenter and Moss suggest consulting the history of medicine:

Just as physicians once believed that the only effective way to treat infection was to cut it out surgically, it is commonplace today to believe that capture can only be treated by “amputating” the offending regulation. Fortunately, the evidence that emerges in this volume suggests that less drastic remedies may be equally if not more effective, and that some are already working—like the body’s own immune system—almost invisibly behind the scenes.

The Tobin research is a call for “reaching a new level in the treatment of regulatory capture.”

That deeply empirical research, which identifies certain regulatory bodies with “surprisingly strong immune systems,” yields all sorts of practical suggestions for mitigating capture: consumer empowerment programs; cultivating diverse, external expert advisers; expanding federal review of regulatory actions to include inaction (where an agency has been stymied by an interested party). Some of these techniques have already been implemented—for example, by building a consumer advisory board into the new Consumer Financial Protection Bureau.

“Our ultimate goal,” says Moss, beyond any accompanying gains in practice, “is to help ensure that tomorrow we have a deeper understanding of the problem of regulatory capture—and how to limit it—than we do today.”

Taking Risks with Ideas

The Tobin Project came through trial and error to its present, effective model for catalyzing transformative social-science research and identifying significant problems on which to work. Last year, the organization received a MacArthur Foundation Award for Creative and Effective Institutions, which recognizes “exceptional organizations that…generate provocative ideas, reframe the debate, or provide new ways of looking at persistent problems.”

Once a research priority is defined, the Tobin Project is careful to assemble a group of scholars that spans disciplines and generations. When graduate students sit alongside Nobel laureates, it has found, youthful energy meets with the wisdom that comes with experience, challenging all involved to think in new ways. Inviting each group to answer a question, as opposed to talking about an issue, helps orient the discussion so the scholars consider, and learn from, one another’s perspectives—productively moving beyond their expertise in their own fields.

Unsurprisingly, perhaps, this model of cross-disciplinary dialogue and engagement reflects who Moss is as a scholar, and the lessons he absorbed from his mentor, James Tobin. Colleagues describe Moss as extraordinarily versatile, with a unique ability to think deeply and insightfully across a variety of topics, and to find strategic ways into big issues. (His own scholarship focuses on the roles of government, including risk management, and putting recent developments such as the financial crisis in historical perspective; see “An Ounce of Prevention,” September-October 2009, page 24.)

As the Tobin Project hews to its careful process, meticulously setting up the conditions to encourage new insights, “The risk-taking happens with the ideas,” says Stephanie Khurana. For example, the inequality group is trying an entirely new approach, with no guarantee it will pay off.

Moss is not interested in an intellectually cautious approach. As models for boldness, he often turns to science and medicine, telling the story of Hungarian physician Ignaz Semmelweis, whose discovery that deaths could be prevented if doctors washed their hands before delivering babies initially met with intense resistance. “This was a very risky idea, because it was threatening to the way people thought about the problem,” says Moss. “It implied that doctors were killing people.”

Or, consider the career of Moss’s uncle, the late cancer researcher Judah Folkman, M.D. ’57, who made the revolutionary discovery that tumors recruit their own blood supply. When Folkman first started investigating this path, colleagues told him he was wasting his time; it was so different from what anyone else was working on that they couldn’t see its potential.

Again and again, Moss returns to the idea that research can be transformative, not only in medicine but in the social sciences as well. Today it seems obvious that hand-washing saves babies’ lives, that cutting off a tumor’s blood supply can stop its growth, and that greater liquidity can keep a recession from becoming a depression. Once, these things were not so obvious—and this is another way of stating the Tobin Project’s mission. “We ask, what are the big problems that seem to defy understanding today, but that could become manageable through the advancement of knowledge tomorrow,” says Moss, “and how can we increase the likelihood that transformative research will help to generate that knowledge, opening the door to solutions that may feel obvious one day, but that aren’t obvious to us now?”