Architect Josep Lluís Sert designed Harvard’s married-student housing complex, Peabody Terrace, which opened in 1964, as a modern neighborhood. The quadrangles offer plenty of outdoor spaces, some with views of the Charles River, for playing and picnics. Common rooms encourage social gatherings. Elevators geared to stop at every third floor opened up more space for larger units on the other floors, and enabled tenants to meet each other more easily while coming and going along corridors and stairwells.

This approach, many believe, also helped Peabody Terrace tenants launch what has become the University’s longest continually operating daycare program: today’s Peabody Terrace Children’s Center (PTCC). It originated as a nursery school founded in 1964 by a core group of mostly young mothers, pioneers in the nascent move to create what’s now called “a work-life balance.” PTCC director Katy Donovan, who began there as a teacher 30 years ago, credits Sert with helping “tenants to find a community in this concrete structure, which was very much international housing, and still is,” she adds. “There are stories of families who lived here and became friends because their kids were at the daycare center—and they are still friends, across the globe, all these years later.”

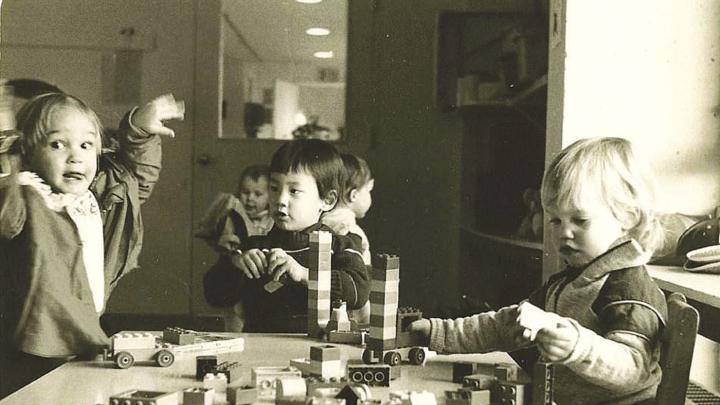

In April about 100 people—current and former teachers, parents, and students, along with some of the founders—gathered at the complex to celebrate the center’s fiftieth anniversary. Amid food and drinks, they caught up on news and marveled at various former children who came to prove they’ve grown up. Blown-up photographs of the early days showed children playing with blocks, climbing jungle gyms in the playground, and taking trips to the river, much as they still do. Barnard associate professor of psychology Tovah P. Klein, a special guest, lectured on her new book, How Toddlers Thrive. PTCC’s facilities, which include eight classrooms, ingenious playground structures, and even a state-of-the-art atelier (inspired by the Reggio Emilia early childhood education philosophy), clearly impressed Klein, who directs Barnard’s Center for Toddler Development. “Do you know how lucky you are?” she asked. “Harvard knows how to celebrate children.”

The event was spearheaded by one of the PTCC founders, Susan Riemer Sacks, an adjunct professor of psychology and professor of education emerita at Barnard, who contacted many former families and also invited Klein, her colleague, to speak. Sacks recalls moving into Peabody Terrace in September 1964 with her husband, Sanford J. Sacks, M.B.A. ’66, then at the Business School, and their two-year-old, Lauren. It was still a “mud pit” of new construction, she says, smiling at the memory.

They had relocated from Ohio, where family members looked after Lauren while the couple worked, so Susan Sacks was glad to find a notice on a community bulletin board in her building announcing a meeting for those keen on forming a nursery school. “I already had a master’s in psychology and had been teaching,” she explains, but with her husband fully consumed by coursework, “that degree would not have done any good [professionally] without a nursery school,” she adds. “It was really a different era and there was really no childcare, which was clearly dramatically needed.”

She and others, including Ann Scott and Diana Ernaelsteen, set to work. “A group of the most talented, innovative, and educationally creative women came together with a shared vision of what we wanted to achieve,” recalled English pediatrician Ernaelsteen, widow of Geoffrey Searle, M.B.A. ’65, during a phone interview. “I had a one-year-old and a three-year-old and was very committed to the children having an education. And the rooms there were splendid: Sert did a wonderful job. I was immensely happy and made a lot of really good, lifetime friends.”

Despite the myriad building, safety, and public-health requirements to be met, and the need to hire a teacher and buy equipment, the Peabody Terrace Nursery Group was up and running by November. About 50 children were enrolled, and by the spring of 1965, records show, the fee was $6 per week per child. (Full-time care there now ranges from $1,650 to $2,629 per month.)

Ann Scott and her husband, Douglas, M.B.A. ’61, M.P.A. ’65, Ph.D. ’68, traveled from Virginia to attend the April anniversary, during which she walked into the courtyard and looked up at their old apartment. “The children would look out our window and say, ‘There’s a babysitter, and there’s a babysitter,’ pointing at the adults in the courtyard,” she said. The family had moved into Peabody Terrace fresh from three years in Uganda and Ghana, she explained. “The new apartment was a gift. The swift launch of a superb nursery school was another gift. We had an instant neighborhood to support us for three memorable years.”

The PTCC is still run by a parent advisory board, but has grown to serve 80 children daily with a staff of 38. It is one of six childcare centers at Harvard that together enroll about 380 children of faculty, staff, and students: each center is operated as its own independent nonprofit organization, but Harvard pays for the facilities and utilities. “What’s fascinating is that each center has its own unique culture, history, and birth story, coming from different constituents,” according to Sarah Bennett-Astesano, Ed.M. ’08, assistant director of the University’s Office of Work/Life. She researched the history of childcare at Harvard and wrote a 20-page report and chronology as part of her master’s degree work.

Childcare first existed primarily on the Radcliffe campus in the 1920s and 1930s, she reports, “as a way to give young women summer employment.” The first more formalized “day nursery” opened at the Phillips Brooks House in 1941, and evolved throughout that decade “as a way to support families when dad was occupied with the war and mom was probably working.” The close of World War II brought an influx of veterans with families to Harvard, which prompted the expansion and move of childcare services, in 1946, to two Quonset huts on Kirkland Street that accommodated 40 “baby-boom” children (there was a waiting list of 200).

After piecing together scant records, Bennett-Astesano says it appears that “for most of the 1950s and early 1960s, there doesn’t seem to [have been] any childcare operating on the Harvard campus.” But the mid 1960s brought a wider push for care, which, she says, began to be viewed as an important factor in women’s professional development—and liberation.

Frances Hovey Howe ’52, Ed.M. ’73, was one of the principal proponents of childcare at Harvard, and helped found the Radcliffe Childcare Center, which has had various locations and began operating as early as 1968. In a 1972 Harvard Bulletin article, “Who Needs Childcare?” she wrote that Radcliffe graduates “found that having a child eliminated their opportunities to achieve career positions in a highly competitive world.” By 1974, Howe had been appointed the first University Child Care Adviser, according to Bennett-Astesano; during the next six years, she helped oversee the founding, growth, move, or merging of several centers, including the Soldiers Field Park Children’s Center, Radcliffe Child Care Centers, and the Oxford Street Daycare Cooperative—all of which are still open. “It’s a time of growth and vulnerability, so people really do get to know each other.”

Meanwhile, the Peabody Terrace nursery school was flourishing; by 1978 it had been incorporated as the PTCC. It became a full-fledged daycare center with added slots for infants around 1989. Childcare services at Harvard expanded further between 2006 and 2013, Bennett-Astesano explains, and “the centers continue to evolve and build on their histories, while Harvard works with them on modernizations—both in terms of physical space and in their ability to serve today’s workforce.”

For PTCC director Katy Donovan and those who gathered in April, the center and its history highlight the importance of supporting family life, especially at a university. “These centers bring people together—faculty, staff, and students—on an equal playing field,” Donovan says. They also help connect families who come to Harvard from vastly different cultural and ethnic backgrounds. She has seen children who spoke no English when they arrived talking and playing easily with friends by the time they left. Even parents from opposite sides of political divides, who might not have engaged with each other otherwise, Donovan adds, have grown close, even asking about each other’s grandparents who were still at risk at home, such as during the Lebanese and Israeli conflicts of 2006.

“This is a very formative time,” Donovan adds, “when you have young children and you are defining your professional life and who you are as parents, and really who you are going to be throughout adulthood. It’s a time of growth and vulnerability, so people really do get to know each other. Look at Susan Sacks and all of these founders who have stayed in touch for 50 years, based on when their children were here for two or three years a long time ago.”