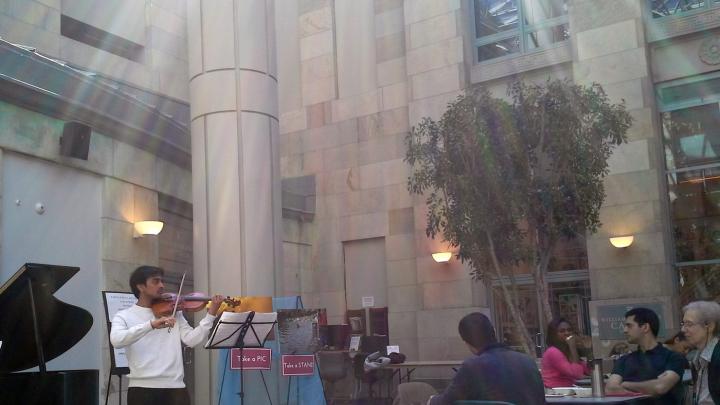

Sunlight streams through the glass ceiling, glinting off the grand piano at one end of the atrium in the Tosteson Medical Education Center (TMEC). It’s lunchtime at Harvard Medical School (HMS). First- and second-year medical students are studying at the tables scattered throughout the atrium as fourth-year students, assured of their residencies, chat with each other, carefree. Ph.D. students take a break from their lab work to eat lunch. Faculty members rush through, en route to or from meetings. Then a woman walks in, seats herself at the piano, warms up with some scales and chromatics, and—without a break or announcement—begins her first recital piece, “Ondine,” from Ravel’s Gaspard de la nuit. Although many in the room continue with their agendas, others pause to listen—and almost everyone claps at the end of each piece.

For a week this spring, the grand piano stood in the TMEC atrium. Performances occurred daily at lunchtime, twice in the early morning before classes, and over the weekend—the culmination of months of hard work by faculty members and medical and dental students, including members of the schools’ student council and the HMS Chamber Music Society. The piano and the week of recitals were one facet of a bigger movement joining medicine with the fine arts—quite literally—as the medical school seeks to integrate the humanities into its traditional curriculum, reflecting the University’s initiative on the arts launched by President Drew Faust in 2008.

Two years ago, HMS faculty and students came together to advocate for the creation of the committee now known as Arts and Humanities @Harvard Medical School. But even before that notable development, proponents of integrating the arts into the curriculum ensured that all medical and dental students would participate during their first two years in small-group discussions that emphasize looking at patients as individuals, not just as fascinating or educational cases. First-years, for example, can take “The Healer’s Art,” a course directed by HMS dean of students Nancy Oriol that focuses specifically on the compassionate and humanistic side of medicine. Fourth-years can take an elective that includes visits to the Museum of Fine Arts, where students explore their ability to “see” the diagnosis by observing images of patients. More informally, students may choose to join the chamber-music group, participate in the traditional second-year show, or become a member of the school’s a cappella group, the Heartbeats.

There is certainly a confluence of values in the arts and medicine—and the 3,000 individuals within the larger HMS community identifying themselves (via an informal survey) as artists are representative of this overlap. Pediatrician Lisa Wong, a co-chair of Arts and Humanities @HMS, a violinist who served as president of the Longwood Symphony Orchestra for 20 years, articulated a clear sense of linkage. The art of diagnosis, Wong explained, requires combining relevant knowledge with creativity that draws on many brain functions—a phenomenon that also occurs when listening to music. Music can help develop a wide range of skills, from basic phonetic education and the art of nonverbal communication to more complex abilities such as pattern recognition—a tool commonly used in medicine. “With music,” she said, “you learn to perfect your playing. There are certain rules within music—if you hear one F-sharp that’s wrong, the piece becomes unrecognizable, and your playing would need to be fixed. That particular attention to detail translates to medicine. We learn to look at chest films, and suddenly you see a shadow in one lobe—it’s a violation of expectations, and you learn to pay attention to it.” With both medicine and music, Wong added,

you never know what’s going to happen—because each piece and each performance is different, and each patient is different. Also, as it is a privilege to treat each patient, so too is it a privilege to play music for others. When we play for an audience, we see the effect it has on other people. You have that experience, too, when you talk with patients. And when you’re performing, you’re sharing such a large part of yourself—but hiding a lot as well. When we talk to patients, we have all had to learn to share emotions with our patients—but again, not too much.

Vocalizing emotions and perspectives was the initial impetus for moving a piano into TMEC. In the weekly “Reflections on Dissection,” held as part of HMS’s intensive introductory “Human Body” anatomy course, students have had the opportunity to utilize metaphors in the arts to deal with the often distressing and conflicting emotions associated with dissecting cadavers. Clinical instructor in medicine Martha Ellen Katz, who began developing the current “Reflections” curriculum five years ago, supported by the course directors, clinical instructors Trudy van Houten and Cynthia McDermott, took an unconventional approach: incorporating paintings, photographs, sculpture, writing, and poetry to mesh the practice of medicine with its metaphysical backbone. “Music not only improves the skills needed to practice medicine, such as listening carefully, communicating clearly, and interpreting even when words aren’t spoken,” Katz explained, “but also opens the door to explorations in addition to the utilitarian that can illuminate meaning, uncertainty, ambiguity, and equity.” Music became “the subliminal as well as the tangible way to express the experiences in the anatomy lab.”

During the past two years, musicians including a cellist, a guitarist, and a string quartet have performed works related to the themes—such as uncertainty, saying goodbye, and exploring silence—discussed at the weekly “Reflections” sessions, held on an upper floor of TMEC. Students regularly opened the classroom windows overlooking the atrium, and the music wafted down to fellow students below. Initially, some neighboring instructors were bothered, but soon they opened their doors to hear the music, too. Thereafter, the idea of using a common space within the school to share music gained momentum, culminating in the week of performances. The presence of the piano in the atrium, noted Federman professor of medicine and medical education Ronald Arky, became the tangible manifestation of “the strong bond between the arts and the basic tenets of medicine.”

The ability of music to move across boundaries and departments set the stage for that unique event. Initial funding came from program coordinator Tania Rodriguez in the Office of Human Resources, but as the project gained strength, Katz commented, “it was good to see how making music could trump territoriality. Here was a project that impacted students, administrators, building staff, and faculty, who all saw its potential, and its shared rewards.” The music, in turn, allowed members of the HMS community to interact with each other on a new level. As one student said: “Every night, a tremendously beautiful thing happened; at around 9 p.m., people would start playing, and others would come out of the society rooms and join to sing. It was joyful and peaceful, and helped to bring us together.” The performances occurred at a notoriously stressful time of the year, when students are usually reminded to set aside time to eat well and sleep, but rarely advised to make time for pleasure. Second-year dental student Ricardo (Ricky) Garza Jr., a member of the student council who led the effort, noted: “We know about the healing power of music…. This is a way to help deal with the doldrums we experience at this time of the year.”

Student response to the musical interludes was almost unanimously positive. Ph.D. candidate Thomas Güttler, a musician who attended most of the performances, called the recitals “a nice break from our daily doings….Usually, music is something that you plan for, prepare in advance, and have to set aside time for. It’s really nice that I can sit here, eat lunch, and listen to music. Music is for everyone, so everyone should enjoy it.”

Just as attendance at the recitals was impromptu, so, too, were some of the performances: some musicians agreed to participate in advance, others joined at the last minute. Pianist Clara Starkweather, an M.D.-Ph.D. candidate who has performed with orchestras in formal settings, said she appreciated the casual atmosphere because her grueling medical curriculum, compounded by lab work in “free” time, barely left her time to practice more than twice a month. Carla Fujimoto, assistant director of student affairs, said the audience’s enjoyment was apparent “just from the expressions on people’s faces in TMEC as you walked by.” Oriol agreed: “You see the students sitting there, and the music suddenly comes into their space….You can see the positive impact it is having.”

As the practice of medicine evolves, so, too, does the medical-school curriculum and the way in which medical and dental students become professionals. Novel efforts to foster that process will help create well-rounded, empathic future physicians. Integrating music within medicine is just a start within the University’s effort to interweave the arts with a traditional curriculum—but at HMS, a harmonious revolution appears to be under way.

Updated August 2: Tania Rodriguez works in the Office of Human Resources, not in the Office of Communications and External Relations, as originally reported.