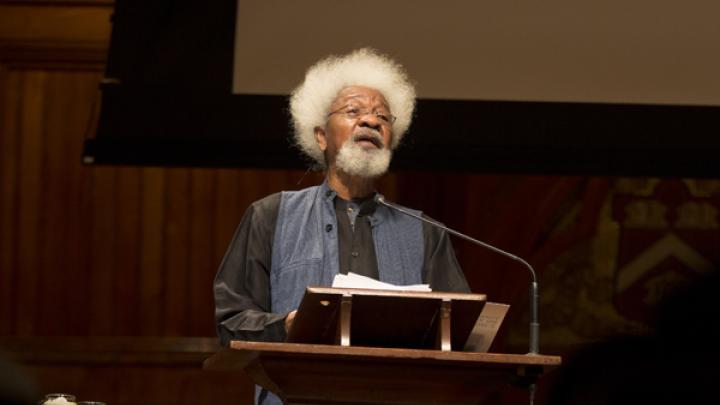

Standing at the podium in Sanders Theatre yesterday, Nobel laureate and Hutchins Center Fellow Wole Soyinka, Litt.D. ’93, recalled learning about the passing of former South African president and anti-apartheid hero Nelson Mandela, his lifelong friend and comrade.

“When I was asked for my reaction, I said, ‘The soul of Africa has departed, and there is nothing miraculous left in the whole wide world,’” Soyinka remembered. “The entire wide world had a love affair with a person called Mandela, including those who were not even born at the time of the Rivonia Trial.” (The Rivonia Trial, in which 10 leaders of the African National Congress were charged with recruiting persons for training in the preparation for a revolution, took place in South Africa between 1963 and 1964; the trial led to Mandela’s imprisonment for 27 years.)

Soyinka was one of many scholars, students, and faculty members who gathered to pause and reflect on the Nobel Peace Prize winner’s life and legacy three months after his death, in an event called “Meanings of Mandela.” It featured prayers, readings from Mandela’s autobiography, music, speeches, and a panel discussion by intellectual leaders with strong ties to South Africa, including Margaret H. Marshall, Ed.M. ’69, Ed ’77, L ’78, former chief justice of the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court; Adam Habib, vice-chancellor and principal of the University of the Witwatersrand; and Achille Mbembe, research professor in history and politics at the University of the Witwatersrand.

After an opening prayer by Pusey minister in the Memorial Church and Plummer professor of Christian morals Jonathan L. Walton, President Drew Faust took the stage, recalling Mandela’s historic visit to campus in 1998, when he received an honorary degree in a special ceremony. Although Faust was not present, she said the legend and memory of that day are so powerful that she almost feels as if she had been. “Those privileged to attend the historic convocation in Nelson Mandela’s honor will always remember a sunlit day in September of 1998 when he shone his grace on Harvard,” she said. “Most of all, though, they remember Nelson Mandela, his radiance and gentle humor, his aura of nobility and humility and integrity, his inextinguishable devotion to freedom and equality, and his inevitable capacity to inspire and to lift every voice… to raise our sights beyond ourselves.”

Fletcher University Professor Henry Louis Gates Jr., director of the Hutchins Center for African and African American Research, then introduced Soyinka—in 1986, the first African to win the Nobel Prize for Literature—who honored Mandela with a reading of his poem, “The Dance Is Not Over.” Like Mandela, Soyinka is known for being a political prisoner—he was arrested in 1967 after being accused of conspiring with the Biafra rebels, and was tortured and held in solitary confinement for 24 months.

“It’s not enough to say that Wole Soyinka shares those values that Nelson Mandela helped to steer—a commitment to social justice and racial equality, as well as the artist’s compulsion both to shed light on these matters, and to write as if one’s life depends upon it,” Gates said. “For Soyinka has in fact, lived that predicament, and that compulsion, for most of his nearly 80 years on earth.”

Soyinka reflected upon Mandela’s style of leadership—a style, he said, that is in harsh contrast to the methods of many modern leaders in the current political landscape. “Take a look around the world today and examine most pertinently the pathetic contrast—the gallery of aliens who lay claim to the leadership of a continent,” he said. “Given the insidious repertoire of religious frenzy, from which I have just emerged, I must be forgiven for succumbing to temptation and proposing a new word to distinguish this species of leaders with which the planet is cursed: I’ll call it bleedership.”

Mandela was a warrior leader, Soyinka pointed out, but he was averse to “bleedership” and proved it by his work in South Africa, and thereby “laid on the world consciousness, an eternal lesson.”

Marshall, who grew up in Newcastle, South Africa, during a time when the government controlled the courts and judges were powerless to declare inhumane the laws passed by the apartheid parliament, called the memorial event “a welcome moment in our busy lives when we can pause and reflect more deeply on his lasting contributions to our world.” Marshall said that although many of the tributes to Mandela have understandably focused on his personal qualities, she preferred to commemorate a different side of Mandela: his lasting commitment to the law.

“I speak to you as a judge, as a woman, as an immigrant from South Africa to the United States, I speak to you as one whose devotion to the rule of law and those who nurture and respect it originates in my own experience of the often brutal abuse of official power in the South Africa of my early life,” she said. “And almost no one experienced that abuse of power more keenly or more intensely than Nelson Mandela.”

Du Bois professor of the social sciences Lawrence D. Bobo, chair of the department of African and African American Studies, recited a passage from Mandela’s autobiography, Long Walk to Freedom. Maria L. Makhabane, M.B.A ’14, of South Africa, read an excerpt from his Nobel Peace Prize acceptance speech of 1993.

After the speeches, a panel moderated by Foster professor of African and African American studies and anthropology John Comaroff discussed topics that ranged from considering Mandela as the greatest peacemaker of all time to exploring some of his private struggles, such as his divorce from his wife, Winnie, in 1994. “Nelson Mandela will continue to be a global icon, a local hero, a cipher for the centuries into which [we] more ordinary souls will continue to pour our aspirations, our arguments for a better world, our sense of nobility,” Comaroff said. “But Tata Madiba [as Mandela is known in South Africa] also embodied the contradictions, the ambiguities… from which all real political figures, all real historical struggles, are ruled.”