The sheriffs announced their arrival with a loud knock. If nobody was inside, they’d have to kick the door in—but at this house, someone was home.

The second-floor apartment was home to Danielle Shaw and her partner, Jerry Allen. On this Wednesday morning in August, Shaw and Allen were at home with young relatives, the children enjoying the last days of summer break.

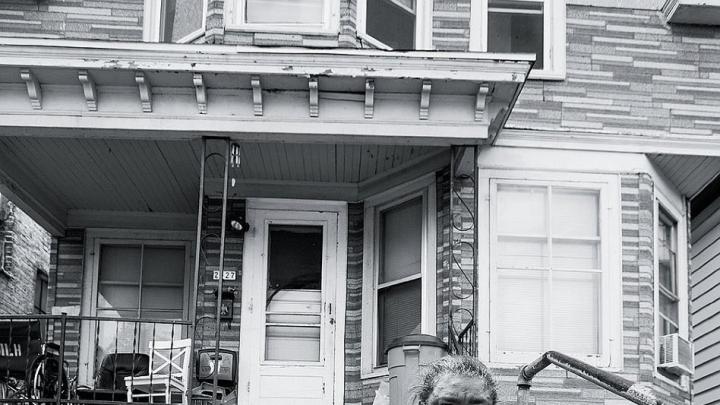

Then the eviction squad arrived: two Milwaukee County deputy sheriffs and five movers, assigned to get the tenants out as quickly as possible. They were accompanied by Matthew Desmond, assistant professor of sociology and of social studies, who studies poverty, housing, and eviction as a force in the lives of the poor.

As Desmond looked on, the deputies swept into the apartment and briskly outlined the process. The couple could choose to put their belongings in storage at the moving company’s warehouse—and pay a fee to retrieve them—or the movers would leave everything on the curb.

The eviction did not come as a surprise—Shaw and Allen had begun packing, and the living room was already piled high with boxes—but the timing did. Allen protested that upon receiving the eviction notice, he had called the landlord, who said they would have 8 to 10 days before actually having to leave; this was only day six. The deputies explained that once an eviction order is issued, it can be enforced immediately; any delay is due to a backlog of cases.

After phoning a friend to ask for storage space at his house until they found a place to live, Allen left to rent a trailer. In their bedroom, Shaw made phone calls to friends and relatives, explaining that they were being forced out earlier than expected. “I don’t see how they get to just put our stuff out,” she told one. “We have nowhere to go.” After hanging up, she sat down on the bed, her expression heavy with despair.

Desmond’s research has revealed just how common eviction is in the lives of poor people, particularly for residents of the segregated inner city. Analyzing court records of formal evictions, he found that in Milwaukee’s majority-black neighborhoods, 1 in 14 renting households is evicted each year—and even this proportion significantly underestimates the number of families whose lives are disrupted by involuntary displacement. That’s because formal evictions can be expensive for landlords—in addition to lawyers’ fees, they must pay court costs and an hourly charge for the eviction squad—so they often work out agreements with tenants, sometimes even paying them cash to move out. Desmond also met landlords who used more adversarial means, cutting off electricity or even removing the front door of a tenant in arrears so that the unit would be condemned and the tenant forced to move out.

These sorts of forced relocations take place off the books. So Desmond collected new survey data from more than a thousand Milwaukee renters to try and capture all involuntary displacements and gain a more comprehensive picture. Working with sociology graduate student Tracey Shollenberger, he found that the most recent move for almost one in eight Milwaukee renters was an eviction or other involuntary relocation; the ratio rises to one in seven for black renters, and fully one in four for Hispanic renters.

Many who are evicted end up in shelters or even on the street. When they do find housing, a record of eviction often means they are limited to decrepit units in unsafe neighborhoods. This transient existence is known to affect children’s emotional well-being and their performance in school; Desmond and his research team are also beginning to link eviction to a host of negative consequences for adults, including depression and subsequent job loss, material hardship, and future residential instability. Eviction thus compounds the effects of poverty and racial discrimination. “We are learning,” says Desmond, “that eviction is a cause, not just a condition, of poverty.”

He believes the acute lack of affordable housing in American cities—the worst such crisis, he says, since the end of World War II—is the primary reason low-income families are being evicted at such high rates. When the real-estate bubble burst, sale prices for homes may have fallen, but rents did not decrease correspondingly. During the last 16 years, median rent nationwide has increased more than 70 percent, after adjusting for inflation. As poor people watched their rent shoot up, incomes remained stagnant: in Milwaukee, for instance, the fair market rent for a two-bedroom apartment in 1997 was $585. By 2008, it had risen to $795—while monthly welfare payments did not rise at all, and minimum wage increases have not kept pace with inflation.

Nationally, between 1991 and 2011, the number of renter households dedicating less than one-third of their income to housing costs fell by about 15 percent, while the number dedicating more than 70 percent of their income to housing costs more than doubled, to 7.56 million. At the same time, housing assistance has not been expanded to meet the growing need: today, only one in every four households that qualify for housing assistance receives it. “The average cost of rent, even in high-poverty neighborhoods, is quickly approaching the total income of welfare recipients,” Desmond has written. “The fundamental issue is this: the high cost of housing is consigning the urban poor to financial ruin.”

As a doctoral student in sociology at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, Desmond was initially drawn to study eviction because of its relational quality: “It brings together poor and nonpoor people—tenants, their families, landlords, social workers, lawyers, judges, sheriffs—in relationships of mutual dependence and struggle,” he explains. The moment of eviction also offers insight into low-income families’ survival strategies and social networks, and into the dynamics of the low-income housing market.

Only after beginning his research did Desmond realize how socially significant—and how little studied—eviction was. No national data exist; he constructed the Milwaukee data himself by examining tens of thousands of Milwaukee County eviction records. In the Milwaukee Eviction Court Study, Desmond interviewed 250 tenants who appeared in eviction court. His Milwaukee Area Renters Study, funded by the MacArthur Foundation, involved in-person interviews with members of more than 1,000 households; the questions covered residential history, employment, material hardship, landlord interactions, and social networks, among other topics.

His findings led him to view eviction and incarceration as twin destructive forces affecting the lives of America’s inner-city poor. Large numbers of previously incarcerated inner-city men (see “The Prison Problem,” March-April 2013, page 38) have difficulty finding work after their release, due to their criminal records—and without demonstrable income, they cannot obtain a lease on their own. Men are more likely than women to work in the informal economy, meaning that women are far more likely to be the “tenant of record” whose name appears on the lease. Yet women leaseholders are generally worse off than male leaseholders from similar neighborhoods, because women earn less on average, are more likely to be caring for children, and, because of that, need larger and more expensive apartments. All these factors increase women’s eviction risk. “If in poor black communities, many men are marked by a criminal record,” Desmond writes, “many women from these communities are stained by eviction.”

Desmond’s fellow sociologists say they appreciate the way he reframes problems and challenges paradigms, instead of simply studying questions identified by others as important. In his Milwaukee fieldwork, he has observed several patterns that led him to identify new problems. For example, he discovered that the presence of children is not a mitigating factor when it comes to eviction: even after controlling for household income and the amount owed to the landlord, tenants with children are more likely to be evicted.

His observations also suggest that the family no longer serves as a reliable source of support for today’s poor, contrary to the long-standing assumption of social scientists and policymakers that destitute families depend on extended kin networks to get by. In a 2012 journal article, Desmond presented a new explanation for urban survival, emphasizing what he calls “disposable ties” formed between strangers. To meet pressing needs, people tended to form intense relationships with new acquaintances—with much sharing of personal confidences, companionship, and resources—that nevertheless frayed or broke off after a short duration. This new category of “disposable ties” thus possessed attributes of both the “strong ties” (intense relationships, usually referring to family or close, long-lasting friendships) and the “weak ties” (acquaintances, distant relatives, or co-workers) of the traditional sociological framework.

Desmond’s eviction study also identified a worrisome effect of “third-party policing,” the practice of shifting the law-enforcement burden to private parties, such as landlords. Working with Columbia University sociology graduate student Nicol Valdez, he studied one form of such policing: “nuisance ordinances” that sanction landlords with fines, license revocation, or even jail time if the number of 911 calls made from their property is deemed excessive. Because landlords often “abate the nuisance” by evicting the tenant who placed the calls, these ordinances force domestic-violence victims to choose between their immediate physical safety and keeping their apartments. After he published a paper on this topic, the American Civil Liberties Union, working with a Pennsylvania woman evicted after being attacked more than once by her boyfriend, filed a lawsuit (now pending) challenging the legality of such ordinances.

Although Desmond’s Milwaukee research is a mixed-methods endeavor involving multiple datasets and a team of research assistants and collaborators, the study began with ethnography, that old-fashioned practice of immersing oneself in a community and recording detailed observations of everyday life. He spent four months in 2008 living in a trailer park on Milwaukee’s south side, a poor, predominantly white neighborhood near the airport, and nine months living in a rooming house in a poor, predominantly black neighborhood on the city’s north side. (The 2010 U.S. census listed Milwaukee as second only to Detroit among the nation’s most segregated cities.) Through this work, he learned about what led to eviction, its aftermath, its context, and what it meant in people’s lives. He writes: “I sat beside families at eviction court; helped them move; followed them into shelters and abandoned houses; watched their children; ate with them; slept at their houses; attended church, counseling sessions, Alcoholics Anonymous meetings, and Child Protective Services appointments with them; joined them at births and funerals; and generally embedded myself as deeply as possible into their lives.”

This intimate view of life in poor neighborhoods informed the way Desmond designed his surveys. It also allowed him to study eviction at the ground level: observing, for instance, which tenants landlords work with and which they throw out. On several occasions, he saw one tenant being evicted while another owing the same amount (or even more) was granted extra time to pay or the chance to work out a special arrangement with the landlord. The eviction decision, he learned, cannot be reduced to simple arithmetic involving how much someone owes; tenants’ gender, race, family status, and style of interacting with the landlord also come into play.

On that Wednesday in August, confusion was the common thread among the three households that were evicted. (Six others had either moved out already or been granted more time). In one case, a woman who worked two jobs (as a school-bus driver and manager at McDonald’s) said she paid her rent on time but the checks were returned to her uncashed after the bank foreclosed on her landlord. She was forced to leave with her two children—including a two-month-old baby. In another, an eviction order was issued when a hospitalized tenant missed a court date because she was recovering from a stroke. She had even been to court the day before the eviction actually occurred, and had been misinformed by her landlord’s attorney that the situation was resolved and that she would be allowed to stay.

Danielle Shaw and Jerry Allen also felt misled. The previous December, before moving in, they had told their landlord that their “money situation was going to be up and down,” reflecting their job situations. Both Shaw, 21, and Allen, 20, had occasional employment (she with a temp agency, he with a building-demolition crew), but were looking for steadier work. Shaw said the landlord told her when she signed the lease, “It doesn’t matter if the rent is late—just pay the late fee.” But when they did fall behind, he initiated eviction proceedings.

Desmond has seen dozens of cases where tenants don’t know their rights, don’t understand the process, and are given conflicting or inaccurate information. In eviction proceedings, most landlords have legal representation, while most tenants do not. For this reason, he advocates increasing access to free legal counsel for tenants.

Very often, his policy suggestions are grounded in trends turned up by his ethnographic research. After observing case after case in which a relatively small unplanned expense led to a missed rent payment and, ultimately, eviction, he also supports the idea of one-time grants for families experiencing temporary financial hardship. (He writes, for example, of one woman evicted from the trailer park who fell behind in her rent after paying her gas bill because she wanted to be able to take hot showers.) With examples like this, he aims to show that every day, poor people are forced to make choices among items that middle-class Americans take for granted, and sometimes must even choose between basic needs, because they can’t afford them all in the same month.

Through his books, articles, and newspaper op-ed essays, he tries to get readers to reexamine how they think about poverty and issues of race. One important point he stresses is that poverty is not innate or permanent, but rather, is influenced by social structures and relationships, such as that between landlord and tenant. “A lot of people talk about poverty like it’s a permanent state of being,” he says, “like the poor are a plant variety.” Instead, he says, poverty is a process that involves a victim, a system that produces poverty, and people who benefit from that system—and he challenges each of us to recognize our role.

By all accounts, Desmond is a versatile sociologist, skilled at quantitative analysis, social theory, and the practice of ethnography. He considers these three methods equally important in influencing social-policy debates to acknowledge problems and move toward solutions. But his colleagues say his talent as a writer, above all, sets him apart. With a style that Eric Klinenberg, a sociologist at New York University, calls “deceptively simple but devastatingly sharp,” Desmond presents the poor in their full and complex humanity, with the hope that his words will motivate action or shift views.

Desmond’s first book, On the Fireline, is an ethnography of wildland firefighters, a familiar population for him: an Arizona native, he spent three summers during college on a firefighting crew, then returned in 2003 to work a fourth season while conducting research for his master’s thesis in sociology.

Whether he is writing about race and poverty or about firefighting, Desmond’s prose displays a lyrical quality and keen observation. For inspiration, he looks not only to other ethnographers, but also to fiction writers—for instance, in this description of the sound of a wildfire: “Giocoso eighth notes of staccato crackles, hisses, and pops skip unevenly across the five treble clef lines while a whole-note rumble—guttural, a continual clearing of the throat—stretches across measures on the lowest ledger.” Or this description of an experienced firefighter driving a truck: “Leaning on the oversized steering wheel, his body tilts and pauses with the engine as if flesh and steel were one.”

The book examines why men (the ranks of wildland firefighters are almost exclusively male) choose to enter such a risky profession, and how their upbringing socializes them to underestimate just how dangerous it is. The reader is a fly on the wall of the fire station, party to camaraderie and discipline as well as lewd talk and practical jokes.

Desmond also explains how these interactions illustrate the unspoken values and unwritten rules of firefighter culture. And his analysis of this culture—both formal training and social inculcation—leads him to conclude that the U.S. Forest Service could better prevent deaths and promote firefighters’ safety by focusing more on teamwork and less on individual responsibility. (He repeated this recommendation in a New York Times op-ed this past July after a wildfire killed 19 firefighters in Arizona.)

It seems natural that Desmond would gain the firefighters’ trust with relative ease; after all, he was one of them. But what about getting poor families in the inner city to open up to him, given the social and racial divisions in American society? Gaining entry requires a good dose of humility and a high tolerance for rejection, Desmond notes, but ethnography, he says, comes with far greater challenges, such as noticing the right things, knowing how to interpret what one sees, and remaining comfortable with confusion instead of rushing to impose order.

During graduate school, Desmond and his wife, Tessa Lowinske Desmond (now program administrator and academic adviser for the Committee on Ethnicity, Migration, Rights at Harvard), lived in a low-income, predominantly black neighborhood in Madison, so “it was not a huge leap” for him to move into poor neighborhoods in Milwaukee for his fieldwork, he notes. Still, reminders that he was an outsider sometimes surfaced at unexpected moments, revealing how complicated and challenging it is to recognize and discard one’s own implicit biases. One New Year’s Eve, he was sharing a meal of chicken wings with fellow tenants at the rooming house. Without giving it a second thought, Desmond asked the woman who had prepared the food if she had a paper towel. The woman and her husband responded with friendly ridicule, remarking on the cost of paper towels and saying he should be content, as they were, to lick his fingers to clean them off.

Desmond sometimes uses a recorder; at other times, he takes detailed notes and fills in more detail at the end of the day. (His ethnographic work in Milwaukee generated more than 4,000 single-spaced pages of notes.) In between research sessions, he hones his craft by looking around instead of staring at his phone while walking to work or taking public transportation. “I dictate observations in my head—observations about storefronts and walking styles and perfume, about little stirring moments,” he explains. “I also force myself to talk with a lot of strangers. Sometimes I’m in the mood, and sometimes I’m not.…It’s a challenge; I have to work at it.”

Although his ethnographic observations eventually feed into scholarly articles about sociological concepts, Desmond has learned that he must sometimes set aside his academic training and just listen while conducting ethnographic research. “That buzzing inner monologue, Jacob Riis and Daniel Bell and [Pierre] Bourdieu all chattering away inside my head, often would draw me inward, hindering my ability to remain alert to the heat of life at play right in front of me,” he said in a talk for fellow sociologists. Being a good ethnographer, he said, “means telling Bourdieu to hush for a minute.”

The skills that make a good ethnographer are not just different, “but opposite, and even antithetical,” to some of the other skills required of an academic, he notes. To do both, one must switch from being outgoing and gregarious to working in solitude; from listening and observing with an open mind to generating insightful conclusions in one’s own mind. Having “shed our scholarly skin,” he says, “we must climb back into it when the season for analysis and writing arrives.” But the insights generated through fieldwork make this awkward transition worthwhile.

Desmond’s own college studies motivated him to confront poverty and racial injustice. The eldest of three children of a Christian preacher and prison chaplain father and a mother who worked with children with disabilities, he enrolled at Arizona State intending to study law. While majoring in communication and justice studies—an interdisciplinary program that combined history, sociology, political science, and law—he recalls that readings about poverty, inequality, and issues of race “blew my mind.” Determined to understand these problems more deeply, he set his sights on graduate school.

At Harvard, he teaches a graduate course on ethnographic fieldwork and a junior social-studies tutorial, “The American Ghetto,” that guides undergraduates in conducting fieldwork in low-income Boston neighborhoods. He spent his first year and a half at Harvard as a Junior Fellow, working on his book about eviction and on The Racial Order, a volume written with Wisconsin sociologist Mustafa Emirbayer, Ph.D. ’89, his dissertation adviser, that aims to put forth a comprehensive theory for the field of race studies.

This is a companion volume to Racial Domination, Racial Progress (2010), a college textbook in which Desmond and Emirbayer use stark facts (and often blistering language) to demonstrate the persistence of racial inequality in the United States. They aimed to create a “non-textbook textbook,” one that “does not reduce one of today’s most sociologically complicated, emotionally charged, and politically frustrating topics to a collection of bold-faced terms and facts you memorize for the midterm.”

Desmond notes that the book is used at a variety of institutions in all regions of the country, and beyond. He hopes that his work will ripple beyond academia to affect American society, in part by opening the minds of college students.

On that Wednesday in August, after the eviction squad wrapped up for the day, Desmond stopped in at a local homeless shelter to see his former roommate, Kendall Belle, who goes by the nickname “Woo.”

Woo’s fortunes had been up and down since his days living with Desmond in the rooming house. Things had been going well—he’d been engaged to be married and had invited Desmond to serve as his best man—but then he was jailed for delinquent child-support payments, and his fiancée left him. Around the same time, he stepped on a nail; Woo thought the wound was healing, but diabetes had caused decreased sensation in the injured foot, and when he visited a doctor to get clearance to go back to work, he learned that the wound was so badly infected that his leg would need to be amputated.

Desmond had visited a few weeks earlier, just after Woo’s surgery, bringing clothing and other items Woo needed and helping him reinstate his cell phone service. While conducting fieldwork, Desmond mostly resisted the urge to intervene. Still, with a deep level of involvement in people’s lives, “friendships are a natural result,” he says. Immersing oneself in a community leads to relationships and reciprocity. Desmond occasionally offered help, as any friend would; he notes that he was also the recipient of much generosity during his fieldwork in Milwaukee (especially remarkable considering the financial hardships affecting most of the people he met).

As the sun began to set, Desmond sat on the cement outside the shelter, talking and laughing with his old friend. Woo would soon be fitted with a prosthesis, and was determined to walk again by Christmas. Next, he would confront the challenges of finding work and housing. For now, though, he had a bed in the shelter; many of the Milwaukee residents evicted that week would not be so fortunate.