Social life and education have long overlapped, collided, and shaped each other at Harvard. Harry Lewis owns a large collection of Harvard course catalogs, and he can show how, in the 1840s, the “catalog” could occupy a single grid with hours of the day down the side and days of the week across the top. Within each cell were just four lines, designating subjects that freshmen, sophomores, juniors, and seniors would be taking at that time. There was no choice. “The social unit was your class year,” Lewis explains. “By the end of senior year, you had sat next to the same guy for eight hours a day, six days a week, for four years.” President Charles William Eliot removed this rigidity from the curriculum, phasing in an elective system during his presidency (1869-1909) that eventually allowed students to take any combination of courses they chose, which broke down those class-year barriers.

The College nearly quintupled in size under Eliot (graduating about 125 students in 1869 and more than 500 in 1909), and students “did not eat together (unless they were in a final or waiting club) or live together, and no longer had their social bonds formed by classroom experiences,” says Lewis. In 1900, a gift from Major Henry Lee Higginson, A.B. 1855, established the Harvard Union as a place to give ordinary students the kind of social experience that only clubmen had hitherto enjoyed—it was a kind of everyman’s club, and could counteract this anonymity. The rise of college athletics in the latter part of the nineteenth century offered teammates another form of social bonding, which the establishment of the Harvard Varsity Club in 1886 and the 1912 opening of its clubhouse, beside the Union, extended. These new institutions tended to break down barriers among students of different College classes, and of different social classes as well. “Let us all be under one roof,” Higginson famously declared.

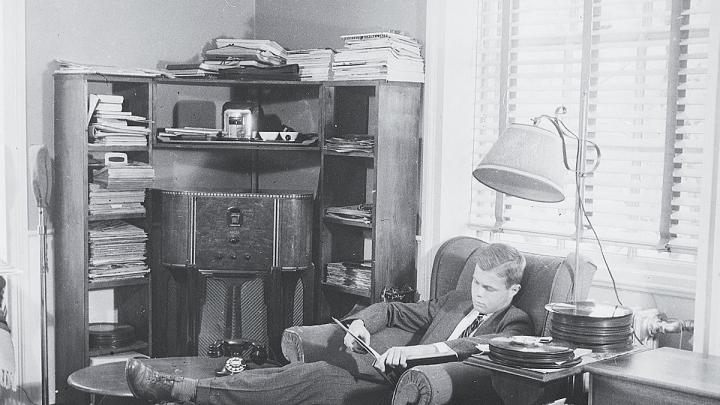

Most students lived at home or in rooming houses, though the wealthy could rent apartments in the luxurious “Gold Coast” brick buildings along Mount Auburn Street (some now incorporated into Adams House). By the 1920s there were freshman dormitories, and seniors roomed in the Yard. That left a gap of two years when students lived wherever they could, and, as Samuel Eliot Morison wrote in Three Centuries of Harvard, “only the clubmen had decent dining choices after freshman year.” By 1926, a report from the Student Council recommended bringing together the three upper classes in residential units with common rooms and dining halls, but it was turned down, to the disappointment of President Abbott Lawrence Lowell. “He felt the College needed to exert a socializing influence,” Lewis says. “Lowell felt that ‘great masses of unorganized young men’ could get themselves into trouble. The houses could help students grow up by being in association with adults—teachers and scholars who would exert some kind of maturing influence on their minds and souls.”

In 1928, Edward Harkness, an 1897 graduate of Yale, walked into Lowell’s office and offered him $3 million to build an “Honor College,” for selected upperclassmen, with resident tutors and a master. Harkness had already offered a similar plan to Yale, but became discouraged by arguments and delays there. “It took Mr. Lowell about ten seconds to accept,” Morison reported, and Harvard’s governing boards moved ahead with such speed and enthusiasm that Harkness soon increased his offer to $10 million to create seven houses for the majority of upperclassmen—three to be built from “the ground up,” and the other four outfitted by modifying existing structures. (Harkness eventually also underwrote the college system at Yale.)

The radical plan aroused both ardor and opposition. The faculty felt Harvard should move more slowly, trying out the house idea with three houses first, to apply lessons learned to their successors. The clubmen resented being herded together with the majority, who in turn lamented the loss of Harvard’s traditional flexibility. The Crimson condemned the plan, and students were generally hostile. They dreaded boarding-school discipline such as the practice of “gating” students (essentially academic house arrest) that had been used at Oxford.

Nonetheless, the first two houses—Dunster, named after Harvard’s first president, and Lowell—opened for occupancy in the fall of 1930 and immediately filled their suites. The other five—Eliot, Winthrop, Kirkland, Leverett, and Adams—were all ready the next year.

Lowell didn’t follow the Oxford/Cambridge model completely. Their residential colleges are academic units with tutors acting as the linchpins of student work. The Harvard houses host tutorials and other academic events, but they are primarily social institutions. Lowell was also trying to break down the gulf between rich and poor, and feared that if undergraduates chose their own housing, a class-bred segregation might establish itself. In fact, it took quite a while before the majority of students lived in the houses, and for a time there were different room rates charged for suites on various floors of Dunster. In the 1950s and 1960s, house masters would interview freshmen to select their incoming sophomores; under its longtime master John Finley, Eliot House, for example, gained a reputation as a haven for prep-school alumni.

In general, though, “this was designed to be a device to promote diversity and contact between diverse groups of students,” says Lewis. Yet the diversity of the 1930s didn’t extend to racial co-mingling: Lowell chose to exclude black students from the houses in what he claimed were their own best interests.