Leading a healthy social life depends on the ability to predict the behavior of others accurately. Most people expect a loud, aggressive bully to be cruel, and a passive, quiet loner to shy away from confrontation. More often than not, that’s correct. Yet exactly how the brain predicts such behavior has long been unclear.

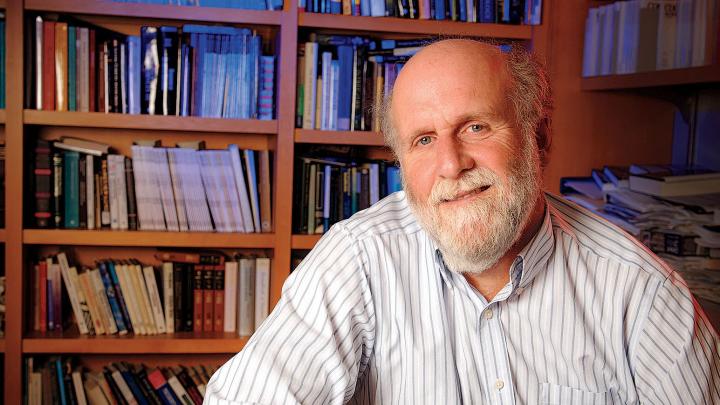

Now research by Kenan professor of psychology Daniel Schacter and several coauthors, published in the March issue of the journal Cerebral Cortex, suggests that the brain, when making behavioral predictions, uses the part devoted to memory.

During the past decade, Schacter says, a revolution has occurred in the field of memory science: researchers have shown that memory is responsible for much more than the simple recall of facts or the sensation of reliving events from the past. “Memory is not just a readout,” he explains. “It is a tool that’s used by the brain to bring past experience to bear when thinking about future situations.”

In fact, Schacter continues, memory and imagination involve virtually identical mental processes; both rely on a specific system known as the “default network,” previously thought to be activated only when recalling the past. This discovery led to a rich vein of research, he reports. For instance, the link between memory and imagination could explain why those with memory problems, such as amnesiacs or the elderly, often struggle to envision the future.

Schacter and his fellow researchers have applied this new way of thinking about memory to the realm of social behavior. If people use memory to imagine their own futures, why wouldn’t they use it to imagine others’ futures as well?

To test this proposition, the researchers presented 19 volunteers with four different protagonists, each with a distinct personality constructed from two variables: extroversion and agreeableness. After the subjects completed a series of exercises designed to familiarize them with the protagonists’ personalities, they were placed in a functional magnetic resonance imaging scanner and asked to consider how each protagonist would react to various social situations—for instance, encountering a homeless veteran begging for change. As the subjects gave their predictions, the researchers analyzed their brain function to ascertain which mental systems were in use.

When considering scenarios about other people, the subjects’ “default network” went to work, just as it did in making predictions about themselves. But the researchers also noticed activity in the medial prefrontal cortex and the cingulate, areas associated with social processing and the creation of “personality models.” This activity was so acute that Schacter and his colleagues, simply by analyzing each subject’s brain activity, could tell whether the person envisioned was the agreeable or disagreeable extrovert, or the agreeable or disagreeable introvert.

The researchers concluded that memory and social cognition therefore work in concert when individuals hypothesize about the future behavior of others. The brain regions responsible for forming “personality models” and assigning them identities are intrinsically linked to the memory/imagination systems that simulate the past and future.