A report on Harvard’s investigations of resident deans’ e-mail accounts last year—prepared by attorney Michael B. Keating, LL.B. ’65, at President Drew Faust’s request, delivered to a Corporation subcommittee July 15, and released yesterday—provides a comprehensive narrative of how news coverage of an Administrative Board review of student academic misconduct led Harvard administrators to authorize the scrutiny of electronic communications, in turn a subject of worldwide news coverage and Harvard concern last spring. Although Keating concluded that the e-mail investigations were motivated by strong interest in maintaining the confidentiality of student records; were conducted in good faith by people who adhered to the University policies they knew about; and did not lead to the examination of the contents of the e-mails, the report raises additional points of interest and some further questions. Presumably, some of those questions will be addressed by a separate task force, chartered by President Faust and chaired by Green professor of public law David J. Barron, that has been charged with recommending new, University-wide policies governing e-mail privacy.

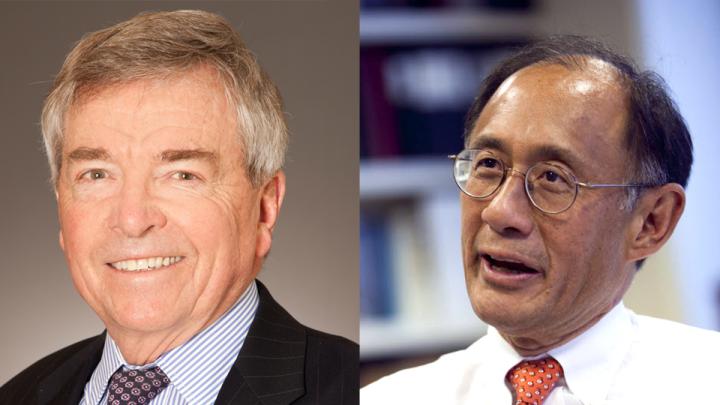

• Knowledge about which accounts were searched. Among the new news in the Keating report is the disclosure that searches of e-mail heading information involving the 17 resident deans who serve on the Administrative Board in fact involved 14,000 accounts maintained at Harvard and 17,000 accounts maintained by an external vendor. The report does not indicate whose accounts were involved, and both Keating and Corporation member William F. Lee (of the Corporation subcommittee to whom Keating reported) said in July 23 interviews that they do not know whose accounts are included in those cohorts. (A query seeking information on whose e-mail accounts are maintained in those HUIT and externally managed pools was pending with the University news office at the time this news story was posted; an update will be posted if the information is provided.)

Keating indicated during the interview that the representative of Harvard’s Office of the General Counsel (OGC) who directed the e-mail investigation knew its objectives; the guidelines governing confidentiality of e-mail messages per se; and the technique of “log” versus potentially more intrusive “mailbox” searches (the former are confined to delivery logs, and can reveal sender, recipient line, subject line, and time stamp, “akin to looking at the information on an envelope but not the letter sealed inside” in the report’s words; the latter affords the IT system administrator access to the actual contents of a mailbox, including, potentially, the text of e-mails)—but would not have “deeply” understood the technological mechanics of the searches per se. This became especially pertinent because, the report notes, Harvard University Information Technology (HUIT) found that it could not perform subject-line log searches for accounts it maintained, and therefore HUIT personnel—operating under the extreme time pressure detailed in the report—ran a search for e-mails to and from The Boston Globe’s higher-education reporter, Mary Carmichael, who was working on the Administrative Board story; according to Keating’s report, “HUIT was not directed by the OGC or anyone in the administration to use the e-mail address of Carmichael to run a log search."

• E-mail privacy policy. Keating’s report uncovered an intriguing lacuna in University and Faculty of Arts and Sciences (FAS) policy. According to footnote 3, page 20, among the policies governing privacy of electronic communications:

The OGC Attorney did not review a policy, entitled “FAS Policy Regarding the Privacy of Faculty Electronic Materials,” which was posted on an Information Security & Privacy website at <http://security.harvard.edu>, rather than the FAS website. That policy had never been approved by the OGC, and in 2012, no attorney at the OGC appears to have been aware of its existence. Also, neither the HUIT Employee nor the FAS administrators who approved the searches knew about it. In 2005, the FAS consulted with the OGC concerning a proposed privacy policy, but the OGC was never advised that the policy had been adopted by anyone or posted to this particular website. Also, as a matter of practice, the OGC is not asked to “approve” privacy policies adopted by different institutions at the University. Further, when the OGC is asked for guidance about whether particular actions comply with applicable policies, it focuses on the policies posted to the website for the relevant institution, such as the FAS website, or printed in the relevant handbook.

This suggests that there are some previously unknown and unwanted gaps in Harvard’s “every tub on its own bottom” culture, at least administratively, and that the OGC and other institutional leaders (not to mention the changing leaders of each individual school and dean’s office, encountering such a situation perhaps for the first time) face some challenges that President Faust if anything understated on April 2 when she told FAS members that the then-state of affairs constituted a “significant institutional failure,” and detailed thus:

I have also discovered that we have highly inadequate institutional policy and process around the rapidly and constantly evolving world of electronic communication. We have multiple policies across the University that vary across schools, with some faculties lacking any explicit policies at all. In the FAS, there are two statements of policy—and they are inconsistent. One can be found in the Faculty Handbook; another appears on a website where one might not immediately know to look for it, and it is not included with other privacy policies on the FAS home page. How these various policies emerged and were constructed, debated, or communicated is unclear. We have also kept inadequate records of actions taken to access email in the past, and, in fact, the state of these records has made it a difficult and extended process to reconstruct past practices.

As William Lee said in the July 23 interview:

We need a set of coherent and integrated policies that recognize that multiple different people with multiple different experiences and expertise may be involved in such cases, and that when such cases do arise, we want to assure that we are coordinated and working together, and that the processes are followed in such a way that we never have to have Michael Keating back to do such an investigation again.

Given the likelihood that Harvard may, in the future, have to investigate cases of professional misconduct or other exigencies, Lee amplified, noting the importance of both coherent policy and informed execution (see the first point, above, about knowledge of e-mail databases and search protocols):

From the Corporation’s point of view, looking forward, we hope we never have another academic-integrity issue of this magnitude again. There will be other issues that require searches—we can’t predict what they will be. We need clearly articulated, widely recognized policies and procedures, so when people are acting in good faith, with the best interests of the University in mind and with urgency, they are clear about what they should do and how they should do it.

• Organizational dynamics. The Keating report repeatedly used language that describes the role of OGC personnel in a seemingly passive, reactive way:

Each of the above referenced searches was undertaken after a decision to conduct the search was made by an administrator, or administrators, from the Faculty of Arts and Sciences (“FAS”). Moreover, attorneys from the Office of General Counsel (“OGC”) consulted with the FAS administrators regarding these searches, and an attorney communicated the directives from the FAS administrators to an employee at Harvard University Information Technology (“HUIT”), who conducted the searches along with an outside vendor. [from the Executive Summary, pages 2-3]

The OGC Attorney was tasked with communicating to HUIT the directives from the FAS administrators concerning these email searches. [page 16]

On September 14, 2012, after the meeting with Resident Dean X, and based on further discussions with Dean [of the College Evelynn M.] Hammonds [chair of the Administrative Board during the academic-misconduct investigation], the OGC Attorney emailed the HUIT Employee with “a number of follow-up requests” for additional mailbox searches of Resident Dean X’s administrative and personal accounts. [page 26]

In the subsequent interview, Keating was asked whether the OGC attorney or attorneys involved in fact had the opportunity to discuss the rationale for and mechanics of an e-mail search, and/or to challenge the decision to proceed with such searches, in the capacity of a counselor. He said, emphatically, as in his own private law practice, OGC personnel did have room to play such a role: to get direction from a client, assess the legality and wisdom of proposed courses of actions, and proceed to execute the agreed-upon action. Without being able to offer verbatim evidence of such input from OGC in this instance, Keating said, he had reviewed enough e-mails from within Harvard between administrators and OGC, and minutes of telephone conferences, to have the strong sense that the OGC attorney or attorneys did have a role in the wider discussion and were able, as he put it, to offer counsel as well as to execute the internal (FAS) client’s instructions.

The report does not detail all of what transpired between September 4, when Hammonds and Administrative Board secretary Jay Ellison, the associate dean of Harvard College, met with the board members and discussed “leaks” with the resident deans, and September 12, when the decision to investigate e-mail accounts was made. Presumably, there were opportunities for seeking out, offering, and receiving diverse perspectives, from OGC and perhaps others, during that period; the adequacy of that consultation and input, if any, is not a subject of Keating’s report. The report makes clear, however, that when the decision was made to investigate e-mail accounts, what Keating called in the interview the “exigencies of the moment” (news reports of the academic-misconduct investigation, students’ interest in having it proceed quickly, the need to maintain the privacy of their records, and the scheduled distribution of sensitive student files to Administrative Board personnel a few days later) loomed large.

Keating’s report makes clear that the OGC instructions on how the e-mail investigations were to be conducted carefully delimited the scope of those inquiries and specified that HUIT personnel were not being asked to open e-mails or review their actual contents.

Keating also said that in his view, and based on his perspective from private practice within his firm, the level of personnel at which OGC involvement and review took place in this instance was appropriate and sufficient.

These critical matters of organizational dynamics and execution—within the context of presumably improved, coordinated, coherent, and communicated policies—might be addressed by the task force chaired by Professor Barron. Interestingly, among its members (most of whom are senior faculty) is Rakesh Khurana, Bower professor of leadership development at Harvard Business School and master of Cabot House, who studies just such questions. At a contentious May 7 FAS faculty meeting focusing on issues of governance, he addressed matters of engagement, soliciting diverse opinions, and valuing wide, divergent perspectives—and was warmly received by those present.

Broadly, the issues here involve organizational structures and a culture that encourage hearing diverse views on alternative courses of action (including but not limited to e-mail searches), the consequences of those alternatives versus e-mail searches, the mechanics and scope of searches that might be effected technologically, and so on—all during moments of tension and time pressure. Such concerns were beyond the scope of Keating’s investigation and report; they remain to be addressed elsewhere—along with recommendations about the appropriate level at which future requests to investigate electronic communications should be reviewed (within schools or by the University as a whole), and the expertise of the people involved in conducting such reviews.

• Corporation involvement. As previously reported, Keating was scheduled to deliver his report by June 30. It was dated July 15 and released July 22. According to William Lee, the report was presented to the Corporation as a whole and discussed on July 17, during its annual summer retreat. The decision was made to release the report in its entirety. This is the first indication, for the community at large, that the report was reviewed by the entire Corporation, beyond a subcommittee consisting of Lee, Corporation members Lawrence S. Bacow and Theordore V. Wells Jr., and Faust.

• Next steps: policy and execution. The detailed narrative of the Keating report, and the mechanics of the e-mail investigations conducted last September, are reflected in President Faust’s July 22 statement accompanying the report’s release. Perhaps its most important message may be found in her third paragraph, particularly the end of the first sentence, addressing policy and implementation:

Unfortunately, the detailed factual account in Mr. Keating’s report deepens my already substantial concerns about troubling failures of both policy and execution. The findings strengthen my view that we need much clearer, better, and more widely understood policies and protocols in place to honor the important privacy interests that we should exercise the utmost vigilance to uphold. A university must set a very high bar in its dedication to principles of privacy and of free speech; these are fundamental and defining values of our academic community. The searches carried out last fall fell short of these standards, and we must work to ensure that this never occurs again. I am grateful that Professor David Barron and the task force I have appointed on electronic communications policy will be creating recommendations for guidelines that will assist us in achieving that goal. Michael Keating’s insights and observations will make a critical contribution to that work. In the meantime, I will be announcing before the start of the fall semester interim protocols governing any searches of e-mails at the University.