More than 100 houses in New England, from the colonial era through the twentieth century, have been turned into public museums. Inherently different from art institutions, these places reveal not only the work of their former inhabitants but the habits, predilections, and even failings that comprised their daily lives. Following is a selection of such museums with Harvard affiliations. (Most are open only seasonally.)Their caretakers are often highly devoted to, and scholars of, their subjects: they can talk for hours, educating visitors as well as eagerly enlivening the past.

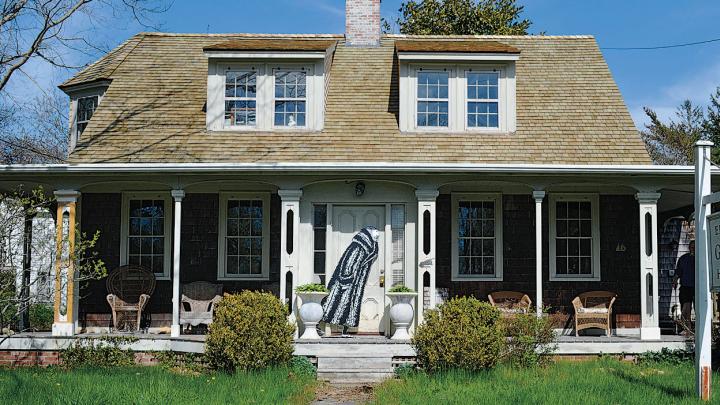

Edward Gorey House

Yarmouth Port, Massachusetts

508-362-3909; www.edwardgoreyhouse.org

The artist and writer Edward Gorey ’50 lived and worked in an 11-room cottage, surrounded by cats and books, for the last 14 years of his life (see Vita, March-April, 2007, page 38). The museum, opened in 2002, displays many of his personal items—boyhood drawings and diaries, typewriter, signature raccoon coat, and the divan in the back room that was ravaged by his clawing cats (he typically had six)—as well as rotating exhibits of his work.

On display through December 29 are the original pen and ink drawings, preliminary sketches, and texts for The Vinegar Works: Three Volumes of Moral Instruction, published 50 years ago. Deemed “whimsically macabre” by the museum, the trilogy contains The Gashlycrumb Tinies: or, After the Outing, a well-known rhyming alphabet book depicting the demise of precisely 26 children: “A is for Amy who fell down the stairs”; “B is for Basil assaulted by bears”; and so on, to “Y is for Yorick whose head was knocked in”; and “Z is for Zillah who drank too much gin.” Printed reproductions fail to convey the delicacy, depth, and richness of his meticulous creativity. “Edward drew every illustration to scale, using these tiny lines,” notes Rick Jones, the director and curator, as he examines the intricate shadows around “Xerxes devoured by mice” as he huddles in a corner. Note also the peeling wallpaper and wood-grained floor of a once-grand room from the series’s The West Wing, a mystery told through interior room scenes that feature a possible dead man in a suit in one and three shoes left on the floor of another. Gorey favored Higgins India ink and a Gillott Tit Quill pen, and could sit for hours in his small upstairs studio—with one view of an elegant Southern magnolia tree—drawing multiple layers of lines the width of a hair, cross-hatching sections to create contrasting images that ultimately offer a three-dimensional quality.

Gorey was a fan of routine. He often ate breakfast and lunch at Jack’s Outback. He saved ticket stubs from events throughout his life (including every performance through 27 seasons of The New York City Ballet under George Balanchine). On the weekends, he regularly shopped at yard sales. “He loved blue glass, beach stones, doorknobs, antique potato mashers, and cheese graters,” says Jones, collecting those things, along with African, Tibetan, and Indian rings and amulets and Coptic crosses (which he also wore). The artist amassed hundreds of such objects that inspired him: he would arrange them into patterns and relationships while he worked. Only once did Gorey leave the United States—in 1975 to see some remote islands off the coast of Scotland. “An interviewer asked him at some point, ‘What’s your favorite journey?’” Jones reports, “and Edward answered, ‘Looking out the window.’”

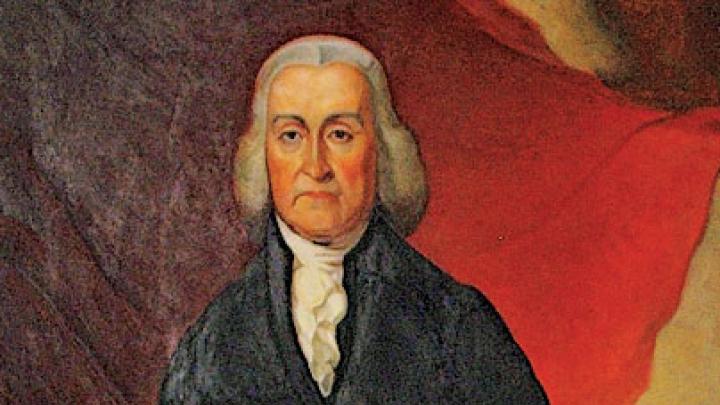

Governor Jonathan Trumbull House

Lebanon, Connecticut

860-642-7558

www.govtrumbullhousedar.org

Jonathan Trumbull, A.B. 1727, was a trained minister and successful businessman who became the governor of the Connecticut colony in 1769—and was the only colonial governor to fully support the cause of independence.

Known for his integrity, Trumbull wrote a letter to British general Thomas Gage shortly after the battles of Lexington and Concord, calling the events “the most unprovoked attack upon the lives and property of his Majesty’s subjects…as would disgrace even barbarians.” He preached restraint, “tempered wisdom,” and continued efforts to “prevent this unhappy dispute from coming to extremities.” Yet he also made clear that “as they apprehend themselves justified by the principles of self-defense,” the colonists “are most firmly resolved to defend their rights and privileges.”

Within days, Trumbull held what would be the first of more than a thousand meetings to organize support for the patriot cause, especially by delivering provisions. He was instrumental in acquiring herds of cattle that were driven down to the troops at Valley Forge, says Cece Messier, a member of the Connecticut Daughters of the American Revolution, which owns the museum. After the food arrived, “‘you could have made a knife out of every bone left on the field,’” Messier says, quoting historic reports.

After the war, Trumbull was the only colonial governor to then govern a newly formed state, a post he held until retiring in 1784. He had actually wanted to follow his passion for ministry, says Messier, but abandoned that career in the early 1730s because his father called him into the family’s mercantile trade. “He did the business to the best of his ability because that was what God put before him to do,” she asserts. “That, and his Harvard education and his dedication to the cause of liberty, made him the perfect person for the Revolution.” Three of Trumbull’s sons, who also played roles in the war effort, went to Harvard, too: Joseph, A.B. 1756; John, A.B. 1773, who was born at the house and later became the famous patriot artist; and Jonathan Jr., A.B. 1759, LL.D. 1809. A statesman in his own right, he also served as governor of Connecticut from 1797 to 1809.

Visitors to the house will learn more of New England’s colonial history—and marvel over antiques, Colonial dish ware, and textiles. Of note are rare handcrafted bed rugs made by Sally Kate Clap, the niece of Nathan Hale, as well as an embroidered depiction on silk, by Trumbull’s wife, Faith, of their daughter Mary’s engagement to the boy next door, William Williams, a signer of the Declaration of Independence.

The Robert Frost Farm

Derry, New Hampshire

603-432-3091; www.robertfrostfarm.org

The Robert Frost Stone House Museum

Shaftsbury, Vermont

802-447-6200; www.frostfriends.org

New England has four properties with ties to the poet Robert Frost, class of 1901, Litt.D. ’37, that are open to the public. “All of the Frost sites are important because they offer different aspects of his life and work,” says Carole Thompson, director of The Robert Frost Stone House Museum, where he lived from 1920 to 1929. “If you know the poems, and you walk around any of the places, you feel like you are walking in the poems.”

Chronologically, the Derry farm came first: Frost lived there with his wife, Elinor, and young children from 1900 to 1911. Surrounded by pastoral scenes, he decided to devote himself to poetry, while also teaching English at the Pinkerton Academy and working the 30-acre property and egg farm, according to Bill Gleed, manager of the state-owned National Historic Site. “He was not a good farmer,” Gleed adds. “The other farmers would hurry past his house because they didn’t want to be asked any questions, or for help.” Frost did attend to the details of the natural world, however, becoming one of the country’s most articulate and lyrical translators of the rhythms and metaphors of rural life (and of his origins as a city boy in nearby Lawrence, Massachusetts). Frost’s first three collections—A Boy’s Will, North of Boston, and Mountain Interval—“were all pretty much inspired by the farm,” according to Gleed. “Mending Wall,” for example, is about his neighbor’s annual repairing of the stone wall that bounded their respective properties, in the belief that “good fences make good neighbors.”

The 1880s farmstead was home to the “Frosty Acres” junkyard before the state bought it in 1964 and largely funded the restoration, guided by Frost’s oldest daughter, Lesley Frost Ballantine. The wide plank floors downstairs, Gleed notes, “are painted red because Rob liked the way they looked with the Christmas tree.”

The Shaftsbury, Vermont, house is near the poet’s gravesite in Bennington. There he composed many of the poems that appeared in his Pulitzer Prize-winning New Hampshire, Thompson says, and planted more than 1,000 red pine seedlings on the grounds. The site offers biographical notes, photos, discussion groups, and lectures, along with exhibits. This summer’s “Robert Frost: The Poetry of Trees” explores his extensive use of tree imagery.

Frost aficionados can also visit The Frost Place, in Franconia, New Hampshire (www.frostplace.org), primarily a nonprofit educational center for writers and poets, or walk the grounds at The Robert Frost Farm (also called the Homer Noble Farm), in Ripton, Vermont (www.frostfriends.org/ripton.html), and see the cabin where during the warmer months he wrote and hosted literary friends during the last 24 years his life. The property is owned by Middlebury College, where Frost was an integral member of the Bread Loaf School of English and a founder of the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference. “He is very much a poet of place,” Thompson says, and recites from a 1936 Bread Loaf class lecture Frost gave: “Literature begins with geography, with love of home and parents. Out of the ground comes poetry, out of poetry, philosophy, and out of philosophy, all that we are.”

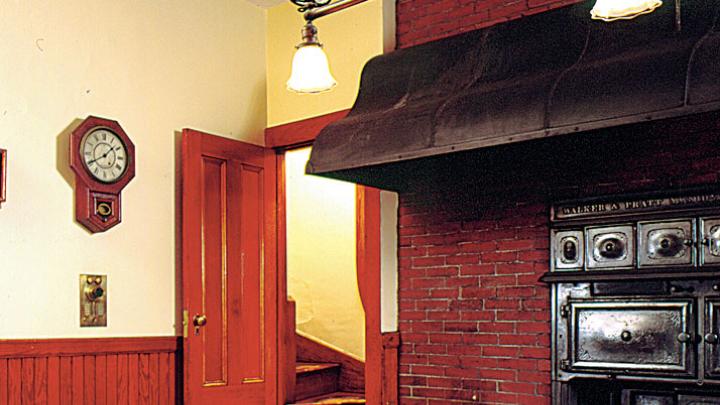

Phillips House

Salem, Massachusetts

978-744-0440; www.historicnewengland.org

Visitors to this art- and antique-packed, Federal-style manse will learn about the life and times of trust-fund manager Stephen Willard Phillips, A.B. 1895, LL.B. 1898, his wife, Anna, and their son, Stephen “Stevie” Phillips ’29. Although “they were not presidents and did not play a huge role in American history,” says site manager Julie Arrison, “they represent a lifestyle of the mid-twentieth century.” Four generations of the Phillips family, as well as other relatives, attended Harvard: the family also established the The Stephen Phillips Memorial Scholarship at Harvard in 1971 for New England students who demonstrate “strong citizenship and character,” as well as academic excellence. The house makes a perfect College scavenger hunt site: Who can spot the teddy bear with the crimson and white sweater? Find the Class of 1929 watch box, and the Veritas wall plaque—and the collection of “President’s Reports of Harvard College.” The Phillipses were affluent, well-traveled—and clearly cared about education. Stephen Willard Phillips owned more than 10,000 books, most of which he had read, and seriously studied and collected Polynesian and Hawaiian art. Pieces are on display—note the hand-carved Fijian war club—along with Chinese and Japanese jade, ceramic, and wooden objects from other trips. “He was actually born in Hawaii because his father, Stephen Henry Phillips, A.B. 1842 [whose own father was Stephen Clarendon Phillips, A.B. 1819], was the first attorney general to the kingdom,” says Arrison, who works for Historic New England (founded by yet another alumnus, William Sumner Appleton, A.B. 1892), which owns the house museum, as well as 35 other properties well worth visiting.

In 1911, when the family moved in, Anna Phillips renovated the house, eliminating the dark Victorian interiors and enlarging the windows. She also added modern bathrooms, a gas stove, and the latest in kitchen gadgetry: look for the aluminum manual bread maker and a “green bean Frencher” that sliced the pod just so. (Arrison often runs special tours on culinary history and technology, her specialty.) A custom-made monogrammed set of rose medallion china was for company, she notes, while the family ate its nightly five- or seven-course meals on the “everyday” Limoges and Canton ware. A sample menu offers “orange fairy fluff” for dessert.

Five staffers helped the three-person family: a cook, first-floor maid, nursemaid, a coachman/groundsman, and a chauffeur who likely drove the 1924 Pierce Arrow Touring Car or the 1936 Pierce Arrow Limousine stored in the rear carriage house. Historic New England emphasizes the “upstairs/downstairs” relationships, along with personal stories of the Irish immigrant experience. Harmony generally prevailed, Arrison reports, although boundaries were clear. Anna Phillips rarely, literally, stepped into the kitchen, and the domestic staff lived on the simply furnished third floor and were on call 24-7. “The family was very particular and never called them ‘servants,’” she explains. The live-in “girls” stayed on even after Stephen Willard Phillips died in 1955. Although “Stevie” grew up, married, and moved next door, he requested his childhood home, and its collection of five generations’ worth of belongings, be preserved and opened to the public after he died. The museum opened in 1973. “Because they cared about their traditions and their house and objects, they saved everything,” says Arrison, down to years’ worth of handwritten receipts for meat and produce. “We’re lucky to have such a complete record that can tell the historic story of how this family and many others lived as America was moving into the modern age.”

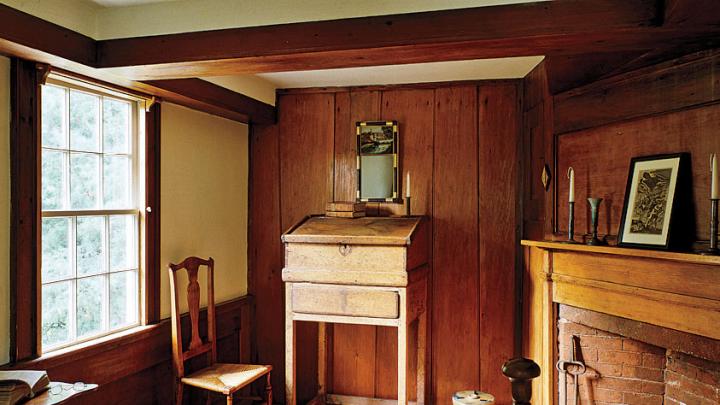

Jonathan Fisher House

Blue Hill, Maine

207-374-2459; www.jonathanfisherhouse.org

Even by the standards of his day, Jonathan Fisher’s multiple talents and lifelong productivity were highly unusual. He was reared in a Massachusetts Puritan community, graduated from Harvard in 1795, then moved to Maine to become the first settled Congregational minister in the coastal village of Blue Hill. There, he designed and built his house, which has been altered by additions and deletions in ensuing years. He was also a farmer, scientist, mathematician, surveyor (creating his own tools), furniture-maker, writer—and taught himself art. “His passion in life was more art and architecture and math than it was religion, although he was a good minister for 50 years, and it fed his family,” says Amey Dodge, president of the Jonathan Fisher Memorial, which owns and operates the museum. “People come from all over the country to see his furniture, folk art, and paintings. He just created a huge number of beautiful things.”

The house displays some of his self-portraits, and still-life depictions of flowers, vegetables, and animals. There’s also a watercolor of Harvard’s Hollis Hall. For more than 15 years he worked on carving the woodcuts and printing the illustrations, on his own press, for two books: The Youth’s Primer (1817) and Scripture Animals (1834). The latter, considered an important early American work, is a 350-page compendium of creatures and text from the Bible and is the subject of the current exhibit, A Wondrous Journey—Jonathan Fisher and the Making of Scripture Animals, at Maine’s Farnsworth Art Museum, which owns much of his work.

Fisher also spoke six languages, fulfilled his parsonage duties—writing and preaching more than 2,000 sermons—and was a founding trustee of the Bangor Seminary, often walking the 40 miles there. “They were not wealthy people,” reports Dodge. Fisher and his wife, Dolly, worked hard to feed their nine children, even taking in boarders and tutoring students. The whole family made buttons, shoes, and hats to sell. Fisher also made prints and often made money recording public events, including hangings. “He’d write a biography of the person, and maybe do a sketch,” Dodge explains, “then go to the hanging and sell them for two or three cents.” During tours, visitors often wonder “how he found the time to do all of this,” Dodge allows. “He was creative, industrious, and resourceful. And how he chose to spend his time and life is an important example of what we can do when we want to.”

Other Area House Museums with Harvard Connections

Hildene

Manchester, Vt.; 802-362-1788

www.hildene.org

Summer home of Robert Todd Lincoln, A.B. 1864; his popularity on campus soared after his father’s election.

The Glass House

New Canaan, Conn.; 203-594-9884

www.philipjohnsonglasshouse.org

Architect Philip Johnson ’27, B.Arch.’43, called the 47-acre property his “fifty-year diary.”

Historic New England

Boston; 617-227-3956

www.historicnewengland.org

The nonprofit owns: Cogswell’s Grant (Bertram Little ’23 and Nina Fletcher Little, filled with American folk art); Marrett House (Maine minister Daniel Marrett, A.B. 1790); Nickels-Sortwell House (industrialist Alvin Sortwell and his sons: Daniel, A.B. 1907, Edward, A.B. 1911, and Alvin, A.B. 1914); Otis House, (Harrison Gray Otis, A.B. 1811, politician and developer of Beacon Hill); Quincy House (controversial Harvard president Josiah Quincy, A.B. 1828); and the Gropius House (Bauhaus founder and Harvard professor of architecture).

The Trustees of Reservations

Beverly, Mass.; 978-921-1944

www.thetrustees.org

The nonprofit owns: Naumkeag (lawyer Joseph Choate, A.B. 1852); The Old Manse (a center for transcendentalists such as Ralph Waldo Emerson, A.B. 1821); and Appleton Farms (Francis Randall Appleton, A.B. 1875, among other family members who are also alumni).