A team of Harvard scientists led by Weld professor of atmospheric chemistry James G. Anderson announced today the discovery of a serious and wholly unexpected risk of ozone loss over the United States in summer. The finding, published in advance online on July 26 at Science's Science Express website, is startling because the complex atmospheric chemistry that destroys ozone has previously been thought to occur only at very cold temperatures over polar regions where there is very little threat to humans. (A large hole in the ozone layer persists over Antarctica.) The discovery also links—for the first time—ozone loss (an issue around which world leaders successfully organized to ban chlorofluorocarbons, or CFCs) to climate change (a global problem that has so far proven politically intractable).

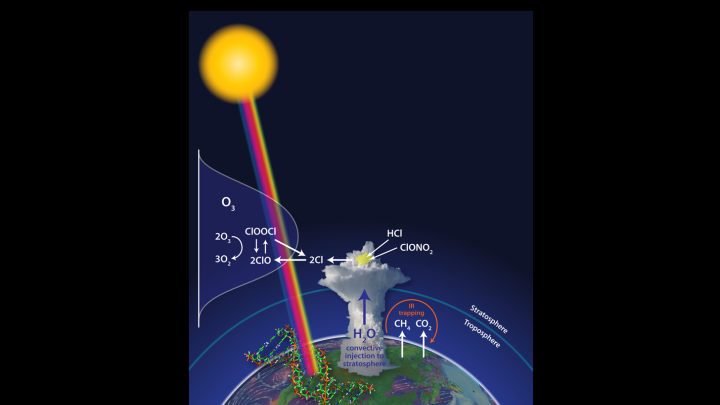

The ozone layer blocks a large fraction of the sun’s ultraviolet light from reaching the earth, protecting life forms from potentially damaging radiation that in humans can lead to skin cancer. But stratospheric ozone is susceptible to chemical catalysts of manmade origin, such as chlorine and bromine, which are present in the earth’s atmosphere as a result of the formerly widespread commercial use of CFCs. And the chemical reactions that destroy ozone are highly dependent on both atmospheric temperature and the presence of water vapor.

Anderson’s team has discovered that during intense summer storms over the United States, water vapor is thrust by convection far higher into the lower stratosphere than previously thought possible, altering atmospheric conditions in a way that could potentially lead to substantial, widespread ozone loss throughout the ensuing week. The paper links the loss of ozone over populated mid-latitude regions in summer to the frequency and intensity of these big storms, which could increase with climate change resulting from rising levels of carbon dioxide and methane in the atmosphere.

“We were investigating the behavior of convective water vapor as part of our climate research,” Anderson says, “not ozone photochemistry. What proved surprising was the remarkable altitude to which water vapor was being lofted—altitudes exceeding 60,000 feet—and how frequently it was happening.” Anderson and his team realized the significance of the finding because higher water- vapor concentrations in the cold reaches of the lower stratosphere change the threshold temperature at which chlorine is converted to a free radical state: in the presence of water vapor, direct catalytic removal of ozone takes place at warmer temperatures.

In continuing studies the team used isotopic signatures to demonstrate that the water vapor had been carried directly to the stratosphere as a result of convective injection. And in the region of convectively injected water vapor, the researchers found that the catalytic loss of ozone increased by a hundredfold. As a result, rates of ozone loss could exceed the natural rates of ozone regeneration (and replacement through transport from other regions) by two orders of magnitude. These data come from experimental evidence gathered over the United States, but the researchers note that similar conditions may exist elsewhere.

These findings have a public-health impact because they indicate that significant amounts of ozone can be destroyed in only a few days within regions of high water-vapor concentration—and skin-cancer incidence is associated with ultraviolet (UV) dosage levels, which in turn depend on ozone concentrations.

The findings are troubling also because—if the currently extremely dry stratosphere were to become wetter (as happened during earlier periods of elevated carbon dioxide, as indicated in the paleorecord)—the impact on ozone levels could be significant. The high current loading of chlorine and bromine resulting from earlier commercial release of CFCs and halons is unprecedented in Earth’s history. “Were the intensity and frequency of convective events to increase irreversibly as a result of climate forcing,” the scientists write, “decreases in ozone and associated increases in UV dosage would also be irreversible.”

The Science paper notes that loss of ice in the Artic threatens to release significant amounts of carbon dioxide and methane from the soils of Siberia and Northern Alaska, potentially accelerating climate change. The researchers also note that an increasingly cited remedy for climate change—geo-engineering the climate by launching sulfate particles directly into the atmosphere in order to reflect sunlight away from Earth—would accelerate the process of ozone loss by increasing the reactive surface area for the conversion of chlorine to free radical form, as was observed after the eruption of Mount Pinatubo in 1991.

Mario Molina, S.D. ’12, Distinguished Professor of chemistry and biochemistry at UC, San Diego, and co-recipient of the 1995 Nobel Prize in chemistry for his work on CFCs and ozone depletion, says that the findings described in the Science paper are “something very much to worry about, because there is the potential for a pretty significant effect on stratospheric ozone at latitudes where we normally wouldn’t think that would happen.” His own famous 1974 paper on CFC and ozone chemistry, he notes, was largely hypothesis, whereas the Anderson team’s work is based on science that is well-established: even though the results will have to be tested with further measurements, he says that “there is not much speculation” in the paper.

The location of the ozone loss in this case gives special cause for concern. Because the Antarctic ozone hole is confined to the most southern latitudes and only occasionally moves toward the southern tip of South America, scientists have little field experience with biological impacts. “DNA, of course, is constantly being damaged by ultraviolet radiation,” notes Molina, “and there is a natural repair mechanism. But should ozone disappear in the way described in Professor Anderson’s paper, this would very much be a threat. Many ecological systems are quite sensitive to ultraviolet radiation and they have not evolved the repair mechanisms for more severe ozone depletion.”

Molina says this is “a further indication of society having impacts on the environment which in principle we can do something about.” Harking back to the ozone issue, he points out that if there had “been no international agreement to ban CFCs” in the late 1980s, this newly described problem “would have been a lot worse.” He hopes that “these types of warnings will make the case even stronger for society to begin to react to the climate-change issue, just like we managed to do with the ozone issue.”

Ralph Cicerone, president of the National Academy of Sciences and himself an atmospheric chemist, says that Anderson’s group has “come up with a very important overall picture where the individual pieces are well mapped out; they have been studied by the world’s best experts and they work.” How serious the findings are is not yet clear, Cicerone says, “but what the Anderson group is talking about can be measured fairly quickly. It is now just a matter of marshaling the people and resources to investigate further.”

“Then we can figure out what the influence is on ozone,” he continues, “and how much more ultraviolet light penetrates to the surface of the earth, so that we can get to the bottom-line effects on human health, as well as crop and other damage.” If further investigation verifies the Anderson team’s findings, then the impacts in “a future climate where the air is getting warmer and moister” will need to be considered, Cicerone says. Are these storms that “thrust moisture into the stratosphere going to be more frequent?” he asks. “We think they are.”

Anderson’s pioneering work on ozone-loss research, including the first attempt to obtain numerous readings at well-defined altitudes as high as eight miles above the earth by using a tethered balloon, was described in a Harvard Magazine cover story in the January-February 1983 issue.