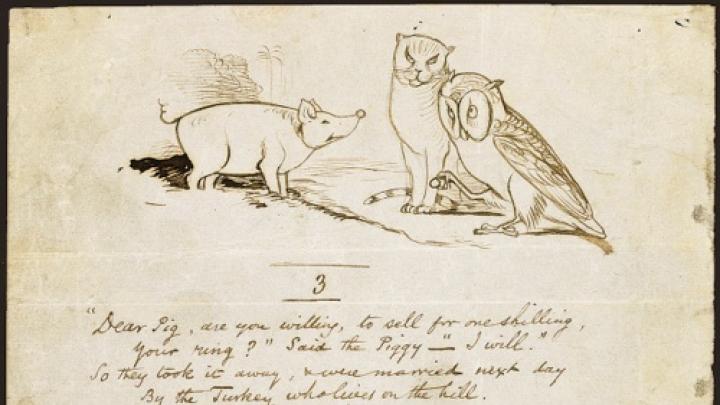

May 12, 2012, the bicentennial of the birth of the English artist, illustrator, and author Edward Lear, was celebrated in certain quarters as International Owl and the Pussycat Day. Lear began to create his nonsense verses, limericks, illustrated alphabets, and whimsical drawings early in life and didn't imagine they would interest anyone beyond his family and friends. When he published the first of them, in 1846, he did so pseudonymously so as not to harm his reputation as a serious artist. He wrote and illustrated "The Owl and the Pussycat" in 1867 to cheer a sick child. Lear's beloved poem may be read online today in more than 100 languages, although translating the nonsense word "runcible" into Hawaiian or Hebrew may have been a challenge.

The Natural History of Edward Lear, an exhibition at Harvard's Houghton Library through August 18, celebrates a different aspect of Lear's career to mark his bicentennial. The library holds the largest and most complete collection in the world of his original artwork and related material—more than 4,000 items—and this exhibition presents a selection of his sketches, studies, and finished paintings of parrots and other subjects of natural history. Robert McCracken Peck, senior fellow of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University, was guest curator for the exhibition and wrote a substantial essay, "The Natural History of Edward Lear," for a double issue of the Harvard Library Bulletin (volume 22, numbers 2-3), which contains as well an essay by Hope Mayo, Hofer curator of printing and graphic arts, about the Lear collection, and a catalog of the exhibition.

"Although he is best remembered today as a whimsical nonsense poet, adventurous traveler, and painter of luminous landscapes," Peck writes, "Edward Lear is revered in scientific circles as one of the greatest natural history painters of all time. During his relatively brief immersion in the world of science, he created a spectacular monograph on parrots and a body of other work that continues to inform, delight, and astonish us with its remarkable blend of scientific rigor and artistic finesse."

Lear (1812-1888) was the twentieth of 21 children born to Jeremiah Lear, a London stockbroker, and his wife, Ann. Most of the children did not survive infancy. The family lived in an elegant house just north of London, but in 1816 Jeremiah suffered a reversal in the stock market, they had to quit home, and most of the children were dispersed to separate households. Lear was raised by his oldest sister, Ann, from the age of four. At five or six he had his first epileptic seizure and a few years later his first acute depression, which he called "the Morbids." He had most of his book learning from Ann, and she was a modestly talented artist who encouraged him in those tendencies. By his middle teenage years, he was making small change selling drawings to stagecoach passengers in inn yards and doing drawings of diseased flesh for hospitals and doctors.

He became an habitué of the new London Zoo. Soon, his subjects were not dead people but parrots, who carried on at the zoo or in nearby private collections owned by patrons he met through the zoo. Now, writes Peck, he "was reveling in the company of beguiling birds."

When in 1831 he published plate seven of his book Illustrations of the Family of Psittacidae, or Parrots (opposite), which appeared in parts, it was hailed as one of the finest bird pictures ever made. Houghton Library has several of Lear's preliminary studies for this plate (including the one at the beginning of this article).

Lear's most generous patron was the thirteenth Earl of Derby. At his estate, Knowsley Hall, near Liverpool, he had a private menagerie and aviary more important than the London Zoo. Lear spent six or seven years there intermittently, portraying creatures. Peck writes that Lear "never enjoyed drawing mammals as much as birds, complaining…that mammals were 'so much more trouble than birds & require so much more time, '[but]…he was equally skilled at both subjects."

By 1836 Lear tired of drawing caged birds and mammals. He increasingly found the English weather detrimental to his always fragile health. His vision was becoming too weak for close detail work. He longed for new subjects, elsewhere. Lord Derby sent him to Rome to study landscape painting.

For the rest of his life he traveled constantly, perhaps restlessly, sometimes with friends; wrote playfully absurd nonsense; painted landscapes; and made only occasional visits to England. His biographer Vivien Noakes aptly subtitled her portrait of Lear The Life of a Wanderer. In 1888, a year after the death of his cat Foss, he died alone but for a servant at his villa in San Remo on the Italian Riviera.

Edward Lear, Study of an Indigo Macaw, now known as Lear's Macaw (Anodorhynchus leari). Watercolor over graphite on paper. Ink on paper.

Courtesy of Houghton Library, © President and Fellows of Harvard College, Harvard University

The Salmon-crested Cockatoo (Plyctolophus rosaceus), also appeared in Lear's book about parrots. Watercolor over graphite.

Courtesy of Houghton Library, © President and Fellows of Harvard College, Harvard University