At a time of deep concern about unemployment, the American economy, and the federal budget, Harvard Business School’s U.S. Competitiveness Project—announced on December 13—today published “Prosperity at Risk,” a sobering assessment of American business competitiveness, based on nearly 10,000 responses to a survey of 50,000 alumni. It finds “a series of structural changes that began well before the Great Recession [of late 2007 to mid 2009] and threaten to undermine the long-term competitiveness of the U.S.” The report’s authors, project directors Michael E. Porter, Lawrence University Professor and a leader in the field of corporate strategy, and Jan W. Rivkin, Rauner professor of business administration, observe:

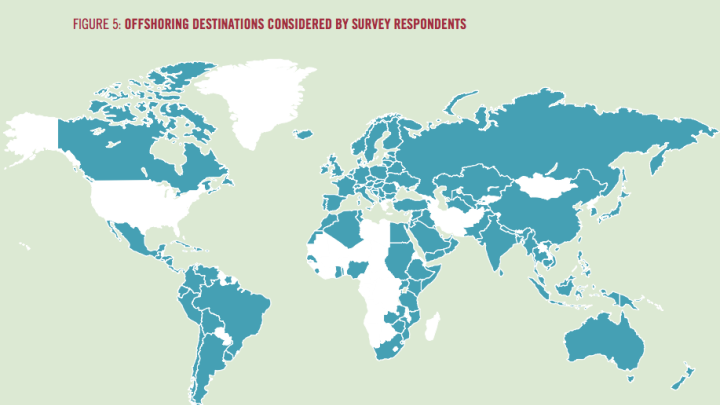

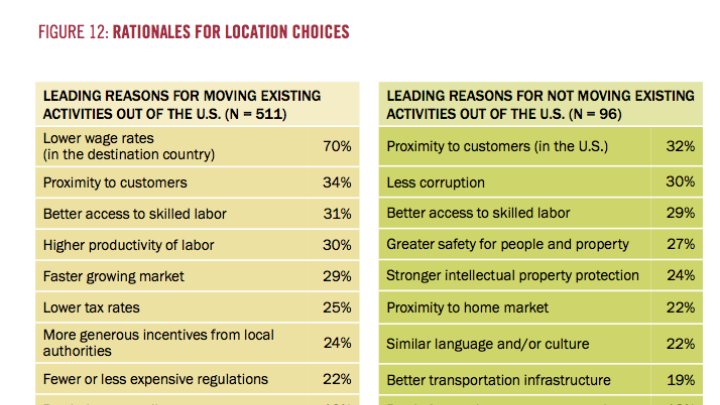

During the past year, more than 1,700 respondents were personally involved in decisions about whether to place business activities and jobs in the U.S. or elsewhere. In these choices, the United States competed with virtually the entire world and fared poorly, losing two-thirds of the decisions that were resolved. Facilities involving large numbers of jobs, high-end work, and groups of activities located together moved out of the U.S. much faster than they moved in.

That is, it is not merely low-wage, low-skill employment that is vulnerable to competition. Indeed, although the survey findings show that “low wage rates” were a leading reason for moving existing activities out of the United States, a slightly larger portion of respondents cited “better access to skilled labor” for decisions to move activities from this country than for decisions to retain such activities (and their accompanying employment) in the United States. (Coincidentally, the National Science Foundation issued a report documenting decreases in state funding for public research universities, where a significant portion of U.S. engineering and technical education takes place; read the news release here. Developing nations, as widely reported, are significantly increasing their investment in such institutions and scientific, engineering, and technical training.)

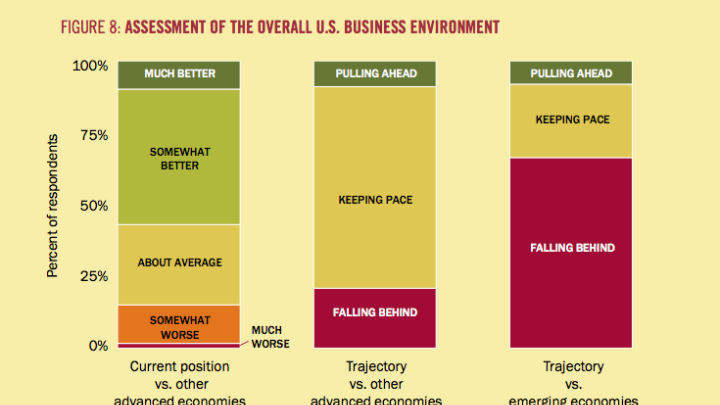

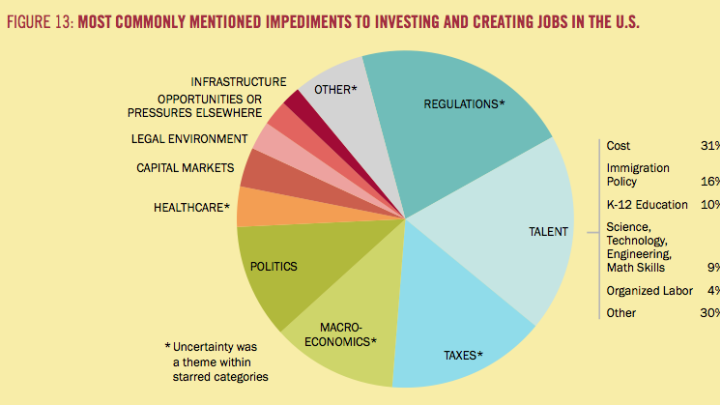

Although the respondents regarded American universities, the context for entrepreneurship, and the innovation infrastructure very favorably as they evaluated the business environment, a majority held the American K-12 education system, political system, and tax code in very low regard. Majorities felt that regulation, economic policy, transportation infrastructure, the complexity of the tax code, K-12 education, and the effectiveness of the domestic political system were all factors in making the United States fall behind in competitive terms. They found far more signs of weak and deteriorating conditions than of strong or improving ones.

"For the first time in decades," Porter and Rivkin write of structural changes in the economy, "the business environment in the United States is in danger of falling behind the rest of the world,” compounding pressure on jobs, wages, and living standards.

“The last time America faced such a moment,” they observe, "was in the 1980s, when competition from Japan revealed quality problems and inefficiency in U.S. firms that had accumulated during a generation of post-war dominance.” They continue:

Then, American leaders from policy, business, labor, and academia engaged in a vigorous debate, came to a shared understanding of the challenges, and pursued a set of public policies and private practices that boosted U.S. productivity and laid the groundwork for two decades of prosperity.

But that’s not what is happening now.

Today, public discourse about the problem and potential solutions often ignores the root causes. Many see jobs as the goal, when in fact it is only through restoring American competitiveness that good jobs can be created and sustained. Many see income inequality as the central problem, when in fact inequality is the outcome of underlying problems in skills, opportunities, and other fundamentals that must be addressed if inequality is to fall. Many call on the government alone to solve America’s competitiveness problem, but business also has a central role to play. The gap between the public discourse and the real issues stands in the way of progress.

The threat to U.S. competitiveness we face today is far more complex than the one America confronted in the 1980s. Now the challenge is not just from Japan, but from many nations with growing strengths and diverse capabilities. The U.S. government is more fiscally constrained and politically gridlocked than it was three decades ago. Leaders of global enterprises are less invested in the United States, or in any single location, than they were in the 1980s. The problems taking root in the American economy are potentially much more serious. Responsibility for the problems cuts across party lines and involves both the private and the public sectors.

In their conclusion, Porter and Rivkin point to joint responsibility for improving matters:

America’s political system, especially at the federal level, is letting us down, in ways that cut across political parties and span Presidential administrations and Congressional sessions. But it would be wrong to place either the U.S. competitiveness problem or its solution at the feet of the government. Business plays a role in creating even those problems that seem to stem from public policy. Take, for instance, America’s corporate tax code. The code is convoluted in part because government authorities have allowed it to be, but also because corporate leaders have relentlessly pushed for loopholes and subsidies that serve narrow self-interest. Part of the business agenda for U.S. competitiveness is to stop taking actions that benefit one’s own firm but, collectively, weaken America’s business environment.

Moreover, business can and must be a positive part of the solution to America’s competitiveness problem. Individually and collectively, firms can upgrade the business environment in the communities where they operate—by supporting educational institutions, building shared infrastructure, investing in workforce skills, deepening clusters, and so on. We are not suggesting corporate charity here. In our survey, we asked each respondent what would happen to his or her company if it undertook more activities to benefit the local community. A full 22% said that the company itself would be more successful as a result. Another 72% said that their companies could do more to benefit the local community without affecting company success. Only 7% felt that doing more for the community would diminish corporate success. Untapped opportunities exist for firms to upgrade the competitiveness of their local communities, and to benefit themselves in the process.

The competitiveness project is a multiyear effort to identify and address these challenges. The March 2012 issue of Harvard Business Review will analyze factors critical to U.S. competitiveness and outline action agendas for “restoring America’s economic vitality.”

Read the Washington Post coverage of the report. The Wall Street Journal's coverage, available to subscribers, noted that the survey respondents said "the U.S. is losing ground to emerging economies, where low wages, increasingly skilled workers, growing markets and proximity to customers frequently trump traditional American strengths such as sophisticated infrastructure, a reliable legal system and effective macroeconomic policy." Reporter Lauren Weber noted that "Corporations have a range of tools they can use to stay competitive, such as shifting operations overseas, investing in productivity and trimming costs. Workers, on the other hand, can't simply move to Vietnam or Brazil to find jobs when U.S. factories or call centers shut down." Her article quoted Rivkin as saying,"We face a bit of a fork in the path. The low road is where America devolves into narrow self-interest, companies exit, the tax base goes down, and the skills base goes down. It's a win-loss scenario. Then there's a win-win scenario, where we see a vastly expanding pie where companies invest in innovation and skills." The article concluded by paraphrasing Porter's observation that "[n]either outcome is inevitable, but so far American government and businesses haven't moved aggressively enough to tackle critical issues such as simplifying the tax code and investing in worker training and skills development."