A seemingly routine, even boring agenda for the December 6 Faculty of Arts and Sciences (FAS) meeting at University Hall—three memorial minutes for deceased colleagues, approval of the Harvard Summer School courses, a report on information technology—in fact yielded some of the most vigorous discussions in recent years.

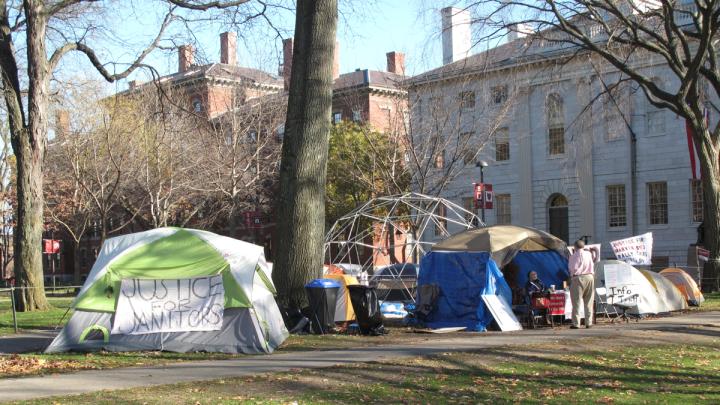

Faculty members and administrators aired issues surrounding Occupy Harvard, which began November 9, and the University’s subsequent decision to lock the Harvard Yard gates and limit access to holders of Harvard IDs and authorized visitors on identifiable, official business.

Photograph from the Janata Party

Subramanian Swamy

Then came an extended exchange on Subramanian Swamy, a long-time economics teacher in the Summer School, whose opinion essay in an Indian newspaper last summer, titled “How to Wipe Out Islamic Terror” (no longer available at the newspaper website, but reproduced elsewhere) provoked controversy worldwide. In the end, the faculty decided overwhelmingly that Swamy had crossed the line between free speech and hate speech—that the actions he advocated (restricting Muslims’ right to vote, razing mosques, and more) rose to the level of inciting violence and deprivation of others’ rights—and his courses were stricken from the catalog of offerings for this coming summer.

Occupy Harvard

President Drew Faust, referring to her statement to the community issued just before Thanksgiving, raised the issue of Occupy Harvard and restricted access to the Yard. She restated the principles outlined then: that two values, of free speech and of safety for resident students and others, must both be upheld. She said she had spoken with many people who held strong opinions on all sides of every aspect of the issues involved. At other Occupy movement sites, including those on campuses, she said, there had been crimes, violence, and arrests: Harvard had an obligation to protect freshmen living in the Yard from exposure to such risks, particularly if the Occupy encampment were inhabited by people who are not members of the Harvard community.

In the meantime, she said, free speech had been “not just sustained but enhanced,” with vigorous airing of the issues in the Crimson, on blogs, at the Institute of Politics, and in informal gatherings—and a planned scholarly teach-in scheduled for the Science Center on Wednesday, December 7. Faust deemed such discussions “essential,” and said the University’s actions were aimed at assuring that they could take place. Therefore, she said, Harvard would maintain restrictions on access to the Yard, and checking of IDs, for the time being, but not “one day longer” than required to maintain safety. The restrictions, she said, were being evaluated daily. She thanked the faculty for putting up with any inconveniences, and for expressing themselves on the issue.

In the ensuing discussion, a faculty member asked Faust if she would report back on a meeting scheduled for December 7 between the Occupy Harvard group and the University’s general counsel, executive vice president, the dean of Harvard College, and a representative of the president's office. Faust said she would do so if anything came of the meeting; she noted that it was not always certain how to relate to Occupy Harvard as an organization because it is so “horizontal” (the movement emphasizes the individuality of its members, rather than designating leaders).

Biodun Jeyifo, professor of African and African American studies and of comparative literature, said he was troubled that the closing of the Yard gates might set a precedent adverse to free speech, and asked whether any alternative measures were available to assure safety. He said the gates had not been locked during the long protests over divestment of University investments in South Africa (when that country was still governed by an apartheid regime), or during student “living wage” protests on behalf of Harvard staff employees and the occupation of Massachusetts Hall (the president’s office) in 2001. The Occupy members themselves regularly discussed security, he said; could their ideas not be taken up?

Faust said that the Yard gates had in fact been closed evenings for about a week [corrected December 9, 2011; previously said one evening], and access had been restricted to Harvard ID holders, during the living-wage protests, when it seemed that there was an “infusion” of outsiders into the protest campaign. The same issue—of participation by nonmembers of the community—arose in the Occupy encampment, she said. She also said that Occupy members themselves had said that Harvard’s security in fact makes it possible for the protestors to focus on discussion of issues, rather than on concerning themselves with safety and security, as has been the case at Boston’s Dewey Square Occupy encampment.

Susan R. Suleiman—Dillon professor of the civilization of France and professor of comparative literature, and interim chair of Romance languages and literatures—rose on behalf of more than two dozen faculty members who had written to Faust to urge that the gates be opened. Faust’s statement, she said, was cogent and in some ways persuasive; but, she noted, the issues of inequality that animate the Occupy movement are global and durable, and won’t be resolved soon. So she wondered, would the Yard ever be truly safe, or would it be locked down for years to come? Was this not an opportunity for the University to take a stand on those issues? She understood that Harvard needed funds, but was it worrying about alienating Wall Streeters and therefore not opposing the inequalities that now exist? Shouldn’t Faust, as president, use her bully pulpit to say that social inequalities are terrible? Suleiman's statement and questions were met with applause.

[The text of the letter to Faust, dated November 22 and provided by Suleiman late on December 7, reads in part:

We the undersigned faculty members of the Department of Romance Languages & Literatures, the Department of Comparative Literature, the Department of Linguistics, and the Committee on Degrees in the study of Women, Gender and Sexuality are writing to express our opposition to the decision to lock the gates of Harvard Yard. We sympathize with your difficult position, but all of us agree that locking the gates is contrary to the principle of open inquiry for which the university stands. Historically, Harvard has never locked its gates (at least, not in recent memory), and we believe that security issues can be addressed differently. We do not share the perception that the Occupy movement constitutes a threat to Harvard. To the contrary, we are in sympathy with protests against increasing inequality in the United States and believe that Harvard should welcome discussions of the issue. We are pleased that in recent years Harvard has taken admirable steps in the direction of greater inclusiveness, both by committing more resources to financial aid and by attempting to recruit a more diverse group of students and faculty. We consider the decision to lock the gates of Harvard Yard inconsistent with the University's commitments to open inquiry and inclusiveness, and urge you as President of this great university to make a public statement about the importance of free inquiry and discussion in the university as you order the gates to be opened.]

Faust said that one had to distinguish between the issues the Occupy movement raises and the means of raising them (the Occupy encampments). Harvard’s decisions on controlling Yard access were aimed at the encampments and safety issues.

On the larger issue of inequality in America, she said, Harvard as a university existed to promote discussion, ideas, and research—and it was doing so in this instance. But she noted, speaking to the faculty as faculty members, “You all take positions. The University does not”—and cannot, legally, and because taking a position on such issues would run the risk of choking off other positions, maintained by diverse individuals, on the same issues. The University makes it possible for faculty members, and others, to advocate any and all views. As an institution, its actions concerning inequality were reflected in its need-blind financial-aid policies and its support of inquiry and dissemination of diverse points of view—but would not be extended to taking a stand on such issues.

A faculty member asked whether news media had asked for access to the Occupy Harvard encampment, and if so, whether it had been granted. A University news official answered “yes” to both questions; Harvard had provided access in the Yard for interviews and still photography, and (as usual) outside the Yard for filming.

A Summer School Instructor and Speech

Subramanian Swamy, Ph.D. ’65, whose residence is listed in the alumni directory as New Delhi, has regularly returned to Cambridge to teach Economics S-110, “Quantitative Methods in Economics and Business,” and Economics S-1316, “Economic Development in India and East Asia,” for Harvard Summer School. The school’s course listing for 2012 came before the faculty for approval; Swamy’s courses were included.

While teaching at Harvard last summer, Swamy—who leads the Indian political party Janata—wrote an op-ed article for Daily News and Analysis, just after three terrorist bombings in Mumbai on July 13. He advocated, among other measures, that India “remove the masjid in Kashi Vishwanath temple and the 300 masjids at other temple sites” (i.e., tear down mosques at presumed Hindu sacred sites); “declare India a Hindu Rashtra in which non-Hindus can vote only if they proudly acknowledge that their ancestors were Hindus” (disenfranchising Muslims and others); and “[e]nact a national law prohibiting conversion from Hinduism to any other religion” and “[a]nnex land from Bangladesh in proportion to the illegal migrants from that country staying in India. At present, the northern third…can be annexed to re-settle illegal migrants.” In the context of the December 6, 1992, razing of the Babri Mosque in Ayodhya, Uttar Pradesh—and the ensuing riots that cost more than 2,000 lives across India, 19 years to the day before the FAS debate—Swamy’s language had explosive political consequences in his country.

As the Crimson reported then, students petitioned the University to sever ties with Swamy. That July 27 article noted, “In a statement sent by a spokesperson, Donald H. Pfister, the dean of Harvard Summer School, said that the school will examine the issue. ‘At this point we have only a basic awareness of the situation and have not been contacted by the organizations involved,’ Pfister said. ‘Professor Swamy is a long-time member of the Harvard Summer School faculty who previously was a member of the Department of Economics here. We will give this matter our serious attention.’” In a follow-up article, the Crimson reported, a Summer School spokesperson acknowledged that the article had been “distressing” to many members of the community, but that Swamy’s right to free speech was protected. (Inside Higher Education also reported on the controversy, and on issues raised in the student petition, such as whether Swamy could teach objectively.)

Because course approvals and appointments of outside instructors, such as Swamy, are annual, the time for examining the issues raised last summer naturally fell to the December 6 faculty meeting, where the vote on the summer school courses was scheduled.

Accordingly, the summer school list of courses was presented for approval, with Swamy’s courses included.

Diana L. Eck, Wertham professor of law and psychiatry in society and Master of Lowell House—a scholar of India’s religions, among other fields—then rose to propose an amendment to exclude Swamy’s two courses from the faculty’s approval. She noted that it was unprecedented for the faculty even to discuss the course listing, but felt compelled to vote against approval if the two courses were permitted to proceed. She cited a letter she and 39 other faculty members had sent to President Faust and Dean Pfister last August concerning (as the letter put it) “comments made by Subramanian Swamy, an economist and former Minister of Parliament in India who has been teaching at the Harvard Summer School for many years.” The letter went on to note:

Swamy used the recent blasts in Mumbai to cast suspicion on India's entire Muslim population. Swamy went on to advocate a shocking series of "counter-terrorism" strategies including the destruction of mosques in India and a denial of basic voting rights to religious minorities unless they "proudly acknowledge that their ancestors were Hindus."

We wish to bring it to the attention of the University administration that a member of our faculty has expressed these extreme views, in a social context that has witnessed episodes of collective violence. We understand that Harvard occasionally benefits from the public profiles of those who teach at the institution, whether they work in business, government, or media. However, we feel that Swamy's public profile is a detriment to Harvard. Freedom of expression is an essential principle in an academic community, one that we fully support. Notwithstanding our commitment to the robust exchange of ideas, Swamy's op-ed clearly crosses the line into incitement by demonizing an entire religious community, demanding their disenfranchisement, and calling for violence against their places of worship. Indeed, India’s National Commission for Minorities has filed criminal charges against Swamy, whose incendiary speech carries the threat of communal violence. When Harvard extends appointments to public figures, it behooves us to consider whether the reputation of the university benefits from the association. In this case, Swamy’s well-known reputation as an ideologue of the Hindu Right who publicly advocates violence against religious minorities undermines Harvard’s own commitment to pluralism and civic equality.

We trust that you share our dismay that someone who purveys inciteful speech in this way is teaching in Harvard's diverse classrooms. We believe that it would be prudent for the Harvard Summer School to be willing to review its appointment procedures in order to ensure that the teachers employed enhance, rather than detract from, the reputation of the university.

In her remarks, Eck emphasized the “destructive” nature of the positions Swamy advocated in India, and characterized the proposals as going well beyond free speech to the advocacy of abrogating human rights, curtailing civil rights, and intruding on freedom of religion. She wondered why the courses had not been “quietly dropped,” rather than submitted for approval in 2012. Swamy’s positions crossed the line to “incitement” and to “demonizing” Indian minorities, and were therefore sharply at odds with Harvard’s pluralism, Eck said. Given President Faust’s planned trip to Mumbai and New Delhi in January, it would be important for people in that country to know where the faculty stood on the views Swamy advocated.

The discussion on the amendment began with a review of how the summer school vets courses. The substantive review depends, in essence, on each department’s view of the merits of a course and the qualifications of the instructor. Although the summer school might view a teacher’s views (as in the case of Swamy) as reprehensible, it had a duty to offer courses as departments determined they were suitable.

Gardiner professor of history Sugata Bose rose to support the amendment, and asked that the vetting of the course and instructor by the economics department be explained. He noted that Swamy had not published in an economics journal for decades, and that there were surely other qualified teachers for the courses. Bose (who has directed the University's South Asia initiative; read his Harvard Magazine review of a recent biography of Gandhi) agreed with Eck’s characterization of Swamy’s article, and noted, further, that Swamy had proposed annexing one-third of Bangladesh; he further noted the anniversary of the December 6, 1992, mosque razing and riots, and put Swamy’s advocacy for razing 300 more mosques in that context. Swamy’s proposed disenfranchisement of non-Hindu minorities would be comparable to disenfranchisement of American Jews and blacks unless they acknowledged America as an Anglo-Saxon nation. Coming as it did just days after the Mumbai bombing, Bose said, Swamy’s article crossed the line from free speech to hate speech.

John Y. Campbell, Olshan professor of economics and chairman of the department, rose to explain that within the economics department, the chair takes primary responsibility, with one other person, for reviewing summer courses, and presents them to the department for approval. It is not easy to find summer teachers, he said, and so there is a bias to continue with teachers who have experience with a course and who receive satisfactory course ratings from students. Swamy had been at Harvard in the 1960s; was a legitimate, published economist; and received satisfactory ratings for his summer courses. Only one student even mentioned the op-ed article in reviewing Swamy’s course, and that student rated it favorably. The department had concluded that Swamy was a competent summer teacher, even if a younger and more academically current alternative might be preferable. The department, Campbell said, expressed its view that it would not take a collective position on academic freedom or on matters of speech, hate speech, or Harvard’s reputation—issues on which there were a wide range of views, in this case, within the department.

Sean Kelly—professor of philosophy and chair of the department—rose to explain the Faculty Council’s 14-0 vote to approve the summer courses of study and bring the list before the faculty. His statement included these views:

Some Council members felt strongly that under no circumstances should an otherwise qualified candidate’s political views be a factor in deciding whether to hire him or her to teach. They felt this was especially true in circumstances in which we were given strong assurances, as we had been both by Chairman Campbell and Dean Pfister, that the political views in question in no way played a role in the candidate’s teaching or the substance of his courses. There was some dissatisfaction from these Council members that we were even having a discussion about the issue. Other Council members felt that this universal principle was too strong, and that there were circumstances in which it is appropriate to use judgment in deciding such cases. In any event, all members agreed that the principle of free speech is one to which a University must be strongly committed, and that it sets a dangerous precedent to fire or refuse to re-hire someone on political grounds alone. Many Council members agreed nevertheless that there are circumstances in which one might naturally be inclined to find so-called political speech disqualifying—such as when it amounts in fact to incitement of violence or perhaps to hate speech, or when it compromises the teacher’s ability to cover course material responsibly. But given the materials available to us [emphasis added], we did not judge any of these to be a factor in the case at hand.

Many Council members agreed that the issues here are delicate. We must balance the University’s identity as a protector of free speech, especially in a political context, with the University’s identity as a protector and promoter of diversity and tolerance. In the end, we felt it was more dangerous for the University to take action against someone on the basis of unpopular or unwelcome political views than it was to run the risk of seeming to be endorsing those views by hiring him for a position unrelated to the expression of them. But we also expected and welcomed a vigorous debate about these issues at the faculty meeting.

(In the subsequent poll, Kelly—and insofar as could be determined, other Faculty Council members present—reversed his vote; as he explained in an e-mail, “For the record, I changed my position on the issue after the discussion at the faculty meeting. I was persuaded, by the addition of new evidence and new context for the interpretation of existing evidence, that the views expressed in Dr. Swamy's Op-Ed piece amounted to incitement of violence instead of protected political speech. I therefore voted, with the majority of faculty members, not to approve his courses.”)

Arthur Kleinman—Rabb professor of anthropology in FAS, and professor of medical anthropology and professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School—rose in his capacity as Fung director of the University Asia Center to offer an “Asianist” perspective on Swamy. He understood the economics department’s judgment of Swamy’s competence as a teacher. But in the context of contemporary India, Kleinman said, Swamy’s article amounted to hate speech and the incitement to violence—matters that would certainly arise in a normal review of a prospective regular faculty appointment. He hoped that the faculty would draw some line. As important as free speech in such instances, Kleinman said, was weighing other evidence: imagine a 1938 appointment, for example, in which a prospective faculty member stood up for Nazism and advocated killing Jews—in which case, he hoped, the faculty would have voted to restrain free speech as it evaluated the candidate. In considering the appointment of Swamy to teach his courses in 2012, Kleinman said, the faculty could choose to use free speech as a cover, or it could address expressed hatred of a minority and incitement to violence.

Sheila Jasanoff, Pforzheimer professor of science and technology studies at the Harvard Kennedy School, who had known Swamy as a graduate student, said that in teaching about India’s development, his teaching was surely touched by his wider vision of the country, its inequalities, and its ethnic diversity. In fact, students had objected last summer—witness their petitions—and expressed their unease. FAS’s decision, she said, affected the reputation of other Harvard schools and faculties as well.

Ali Asani—professor of Indo-Muslim and Islamic religion and cultures; chair of Near Eastern languages and civilizations; and director of the Prince Alwaleed bin Talal Islamic Studies Program—asked whether anyone had queried Muslim students about their comfort level with a teacher who had, in print, expressed Islamophobic views. His question went unanswered.

(In a subsequent conversation, Asani said, “If students know a professor is Islamophobic, how are you going to guarantee that the person’s prejudices are not going to be reflected in grading and evaluating student work?”—a problem that has been studied in other contexts, he noted. Swamy’s views do matter, Asani maintained: “He’s in a classroom before students with a lot of backgrounds, some of them perhaps Muslim.” What safeguards are there? he asked. If this question about student perceptions and comfort had not been pursued, he said, it was important for the faculty to know that: such teachers' views are not separate from the classroom context.)

After further debate, Eck reiterated her amendment, and noted that the faculty faced not “unpopular” views, rightly protected as free speech, but those that “commend an abrogation of human rights.”

With that, the faculty took a recorded vote on the amendment, but it was passed overwhelmingly, with only a handful of votes against, and so a tally was not reported. The Swamy courses having been stricken, the summer school courses of study were approved—and President Faust could prepare for her initial visit to India with the Faculty of Arts and Sciences having dissociated itself from an instructor who advocated highly incendiary views of that nation’s peoples and politics.

Read the Crimson reports on the meeting here and here.