In football, there’s a radical asymmetry between offense and defense. For an offensive play to succeed, all 11 players have to execute nearly perfectly. Thus a pass play may require a wide receiver to run his route flawlessly, secondary receivers to tie up cornerbacks, and the quarterback and running back to deftly fake a handoff and leave the former rolling out—ready to heave a long pass. But perhaps the left guard misses his block, letting a defensive end roar into the backfield for a sack—and the entire play collapses due to one goof-up.

On defense, it’s a mirror image. Maybe a safety was three steps behind that wide receiver and two linebackers bought that fake—but the defensive end’s big play erases those errors and scores a big win for the D. Consider, for example, the moment in last fall’s Harvard-Yale game when defensive tackle Josue Ortiz ’11 burst into the Yale backfield and blocked a punt, then recovered the ball on Yale’s 23-yard line, setting up the Crimson’s go-ahead touchdown in a 28-21 victory.

Offenses run set plays; defenses react, improvise, and wreak havoc. The offense is the Roman Empire, the defenders are Visigoths. (Perhaps it’s no accident that the biggest disruption that defenders can perpetrate is called a “sack.”) “Sacks are the most fun, for sure,” says Ortiz. “It’s like devastating a city, creaming a multitude of people. When you get your sack, you’ve just ended an entire play that 11 guys got together and thought up. You’ve beaten the whole offensive team.”

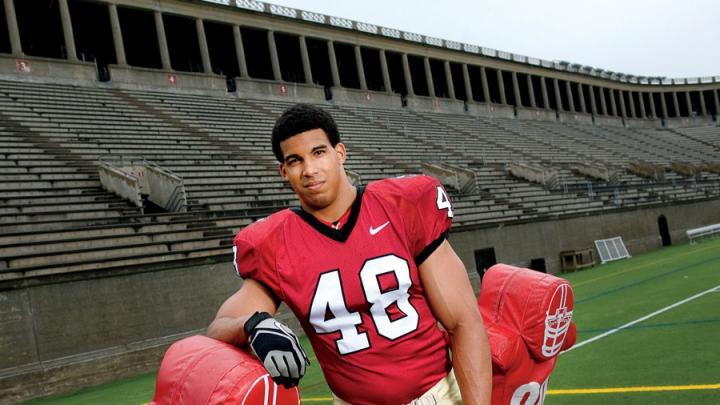

Ortiz knows that satisfaction well: last fall, he led the Ivies in sacks (7.5) and in tackles for a loss (13.5). He recorded two sacks against Dartmouth, a squad that had allowed only one sack by opponents in their first five games. Such performances landed him a First Team all-Ivy berth as well as a spot on the Associated Press all-America third team.

Josue (ho-sway) Ortiz is a “super senior” with one semester to complete, having taken last spring off to work at a Boston law firm. (He hopes to become a law professor.) A wrist fracture two weeks into his freshman season wiped out his 2007 campaign; under NCAA eligibility rules, this fall will be his fourth season of college football.

His Puerto Rican family settled in an agricultural area in central Florida where “cattle outnumber people, five to one,” he explains. It’s a football-saturated region: state champion Lakeland High School, for example, is only an hour away from Ortiz’s hometown, Avon Park. This football-powerhouse background raised expectations, and influenced a pivotal conversation head coach Tim Murphy had with the young defender. After Ortiz played in only three games as a Harvard sophomore, Murphy sat down with him after spring practice the next year. “Coach asked me when I was going to start contributing at the level I was capable of,” Ortiz recalls. “He was right. I had not really dominated or shown any flashes of how good I could be. That summer is when I really got to work and said, ‘I’m going to fix that.’” He gained strength and weight (he’s now six feet, four inches, and 260 pounds) and that fall played every game, led the squad with 9.0 tackles for a loss, and made second-team all-Ivy.

“When Josue came in as a freshman, he was very raw. College football did not come easy to him,” says Murphy. “One thing that was readily apparent, though, was that he had a tremendous work ethic and a relentless attitude, and because of that he has probably improved more than any member of that freshman class. At this point he’s one of the top players in the Ivy League at any position, and certainly one of the top two or three defenders.”

Succeeding on the defensive line largely means finding a way to get past bigger men. Ivy offensive linemen often weigh 300 pounds or close to it. They need good footwork, but not running speed; where a defensive tackle may sprint 40 yards in 4.4 seconds, his offensive counterpart will usually take 5.2 or 5.3 seconds to do so. The O-line’s key job is to block defenders and get in their way, and, as Ortiz explains, “It’s harder to move 320 pounds than 250.” One of his weapons in the one-on-one trench battles is having “tremendous ability to change direction, for someone of his size,” Murphy explains. “Josue has the agility of a guy who is 200 pounds—even though he weighs 260 and can bench press 400 pounds.” That kind of strength allows him to throw those bigger fellows aside. “If he’s going in one direction,” says Murphy, “you’re going in the other.”

His wrestling background also helps. As a high-school senior, Ortiz went 35-4 wrestling at 215 pounds and ranked third in the state. He says that wrestling skills—“aggressiveness, using your height and leverage, quickness, foot speed, hand speed, hand-eye coordination, learning how to get away from people, taking guys down”—transfer well to football line play, which is really a grappling match. In particular, he adds, “hand placement is one of the premier factors,” because although an offensive lineman can control a defender by grabbing the inside of his breastplate, he can also be penalized for “holding” if his hands are on the outside—say, on the shoulders. “If you don’t have proper hand placement you pretty much lose the battle—that’s where it’s won or lost,” Ortiz explains. “When you’re inside his breastplate, that’s where all the control is. On pass-rushing moves, the way you beat blocks is keeping his hands off you.” You have to be quick; in “gunslinger” drills, two linemen starting out with their arms at their sides try to get their hands on the other man’s breastplate first. Similarly with footwork: “The first step is where you make your money,” he says.

An offensive lineman also gains a big advantage from knowing the count—the “secret” number or word that triggers the center to snap the ball. That knowledge allows him to get off the ball and at the defender’s body before the latter knows what hit him. The defender’s counter is to watch the ball closely with peripheral vision while looking straight ahead, and to react instantly to his opponent’s slightest feint or movement. (If the offensive lineman flinches at all, the defender can hit him, because a flinch before the snap is an offside violation.) When scouting opponents with game film, Ortiz and his colleagues sometimes notice how a player with a stripe down the middle of his helmet looks in the direction he intends to move—and the stripe’s motion gives it away.

On the line, a crowd of very big, very strong men like Josue Ortiz are looking for advantages in tiny elements of space or time. Those minuscule edges may not seem like much. But they win football games.