Imagine that, a few years from now, Americans are suddenly plunged into a constitutional crisis. Imagine an economy still muddling in recession; a government rendered inept by the complete collapse of the Senate as a serious institution of deliberation or a continued division between House and Senate; a conservative Supreme Court gripped by a passion to restore the pre-New Deal version of the Commerce Clause (which treated commerce merely as the physical movement of goods across state lines); a militant Tea Party movement convinced that the Tenth Amendment imposes real limits on the lawmaking power of Congress, and is not simply a hollow “truism” saying that Congress can only do what it is constitutionally empowered to do. These days, conjuring up such a vision is not so hard. Imagine that somehow the belief took hold that what the Constitution needed was not a revision here or there, but wholesale replacement.

How would such an act of constitutional change, a modern-day invocation of the people’s fundamental right “to alter and abolish governments,” actually occur? Numerous scholars have written about the changes they would favor. But explaining how those changes would be adopted, either by a drafting convention or the popular ratification to follow, remains a terribly daunting task, not to mention a downright scary prospect.

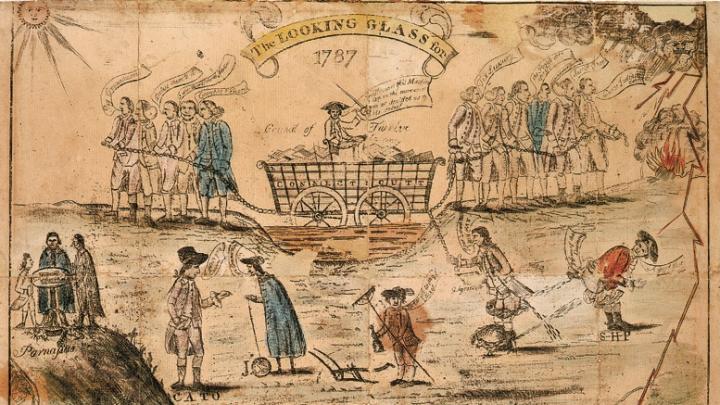

The prospect grows even more distressing when we contrast our own vexed politics with the one splendid example from our history of how an old system can be rejected and a new constitutional regime established. Histories of the framing of the Constitution in 1787 continue to be written (three in the last eight years). Yet our accounts of this process have always tilted in one direction, toward the debates of the 55 framers at Philadelphia, and away from the 11 months of popular deliberation required to get the Constitution ratified. That story of what the people did with the Constitution has never received the full attention it deserved. True, several collections of scholarly essays came out during the Bicentennial of the 1980s, and numerous articles interpret the rival viewpoints of the Constitution’s Federalist supporters and Anti-Federalist opponents. But save for a lone volume by Robert Rutland, a former journalist turned historian, the idea of making ratification its own proper story has never received the attention it deserves.

All that has now changed with Pauline Maier’s much-awaited study of ratification, a book that finally enlarges and completes our understanding of how Americans adopted the Constitution. Her earlier work American Scripture: Making the Declaration of Independence illuminated this country’s other founding document, and similarly emphasized the way in which the Declaration revealed not only the quirks of Thomas Jefferson’s mind, but the concerns and contributions of Americans in communities across the country. In her new book, Maier--’60, Ph.D. ’68, now Kenan professor of American history at MIT--pays special attention to the four populous states of Pennsylvania, Massachusetts, Virginia, and New York, where the debates ran hot and partisan maneuvering proved fierce. The last three states get two well-developed chapters each, and Maier repeatedly asks readers to consider how the debate took the course it did.

Maier conceived her project as a book for the serious general reader, and in many ways Ratification is just that. Yet she is also just too good a historian, with too keen an eye for the complexity of the subject, not to allow her curiosity to take her where it needs to go. The result is a story that reveals how seriously Americans took the constitutional project, and how hard each of the state conventions had to work to determine exactly how its own discussion of the Constitution should proceed. The idea of submitting the Constitution to the people marked a momentous innovation in the practice of constitutional government and the very meaning of the Constitution itself. Yet this was a development for which neither history nor political theory offered any helpful guides. True, one critical precedent was set in 1779-1780, when Massachusetts became the first state to adopt a constitution drawn up by a specially appointed convention and then submit the finished text (mostly the work of John Adams) to the towns for ratification. But pursuing a similar task within a compressed period among the nine states that the Constitution required for approval proved far more challenging.

The entire process got off to a rocky start, Maier explains, because of Pennsylvania, the first state where the Constitution was seriously debated. Pennsylvania was also the most bitterly divided state politically, primarily because of continuing controversy over its radical state constitution of 1776. That earlier constitution’s critics also led the state’s Federalist movement, and they treated this new debate as a convenient opportunity to humiliate their opponents. With a two-to-one majority in the state convention, the Federalists did everything they could to prevent Anti-Federalist views from receiving a fair hearing or even reaching the public. As Maier carefully explains, the resulting suspicions of Federalist purposes and tactics set the uncertain legacy that other states worked hard to avoid.

What worked in Pennsylvania, however, would never do in the three crucial states where nervous Federalists struggled uphill to achieve their ends. In Massachusetts and Virginia, Anti-Federalists enjoyed near or potential majorities, and they were in outright control in New York. In Massachusetts, the Constitution’s opponents lacked effective leadership, a factor that enabled the state’s popular but gout-ridden governor, John Hancock, to intervene decisively when the outcome was still in doubt by endorsing the Constitution and a limited set of proposed amendments. In the other two key states, however, the opponents could rally around the soaring, attack-on-every-front rhetoric of Patrick Henry in Virginia and the political cohesion of Governor George Clinton’s political machine in New York.

Tracing the shifting strategies in the different states and explaining how rules of procedure and key speeches shaped debate, Maier provides a remarkably patient, clear-eyed, and deeply balanced account of this great experimental year of constitutional politics. She is the first historian to take full advantage of the massive Documentary History of the Ratification of the Constitution (21 fat volumes published already, with another eight to go). Most commentators treat the Anti-Federalists with an underlying skepticism, as “men of little faith” who could never fully grasp, much less answer, the compelling political science of the Federalists--whose intellectual champions, after all, were James Madison and Alexander Hamilton. Not Maier. She refuses to call the Constitution’s opponents Anti-Federalists, a disparaging label imposed by the other camp. She carefully reconstructs the debates within the states, not merely to illustrate their special concerns, but also to demonstrate the difficulties they faced in struggling to decide exactly how the Constitution was to be judged.

But Maier is not merely a careful student of these remarkable debates. She brings alive the participants as well. One striking feature of her treatment is the emphasis she gives to George Washington. Most accounts of Federalist politics give greater attention to Madison and Hamilton, the main coauthors of The Federalist, and the leading tacticians in Virginia and New York. By placing Washington at the center of the Federalist movement, Maier reminds us how much this constitutional moment belonged to those who best knew, from their wartime experience, why a national government working independently of the states had to be created (a fundamental point that our current political debates strangely ignore). But numerous lesser lights appear as well, some more cranky than intelligent, but all illuminating what it meant to turn the Constitution over to the people’s delegates for debate.

In an understated way, Maier’s perspective also supports two distinct views of the meaning of ratification. One cautions us not to ascribe too much interpretive authority to the opinions expressed in 1787-1788. The “original understandings” of the delegates to the ratification conventions were filled with gaps and misconceptions the debaters never resolved. Sometimes debates were carefully focused, but at other times they ranged anywhere and everywhere with no satisfactory resolution. Inadvertently or not, Maier’s account of what was actually said explains why latter-day originalists like Justices Antonin Scalia and Clarence Thomas, who treat the final text of the ratified document as sacrosanct, reveal so little serious or sustained interest in the actual debates that adopted the Constitution--indeed, why “originalists” now prefer to play language games about what the Constitution must have meant to ordinary readers rather than reconstruct how it was actually framed and debated.

Yet in the second place, one finally comes away from Maier’s story with a profound respect for the political enterprise and intellectual commitment that made ratification a sublime inaugural moment of American democratic politics. By any standard, what the first generation of our national citizenry accomplished in framing and ratifying the Constitution in little more than a year was remarkable. That does not mean that every decision they took was correct, or should remain secure from our criticism. Our Constitution is riddled with problems and defects, and any of a number of its provisions could be sensibly improved. If I were the lawgiver, I would abolish the equal state vote in the Senate tomorrow, and the Electoral College the week after that. Yet whether our contemporary politics could sustain the task of constitutional revision is an idea we very sensibly doubt. Maier’s account of ratification thus explains not only what happened back then; it also makes clear why this episode merits the brilliant treatment it has finally received.