A skyscraper, unlike a sculpture or painting, cannot be the work of a single artist. It arises from numerous contingencies and collaborations among architects and CEOs, steelworkers and engineers, bankers and billionaires. Like the Great Pyramids of ancient Egypt, the skyscraper is--in our own time--perhaps the ultimate symbol of cultural production. The period since 9/11, thought by some likely to signal the demise of huge towers, has instead seen the biggest surge ever in their construction. Nearly half of the world’s skyscrapers have been built since 2000.

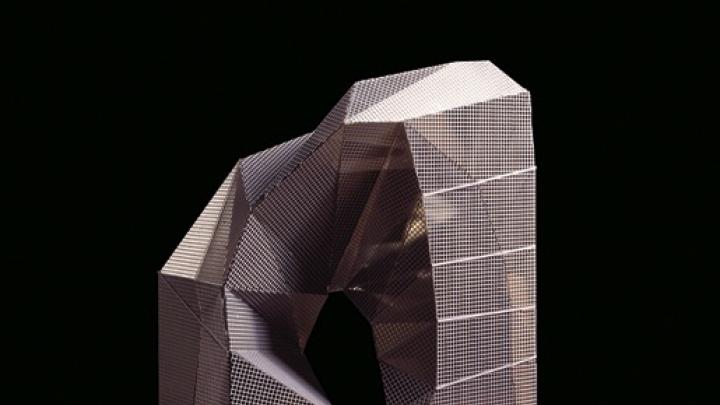

There is “no artifact more synthetic and comprehensive in our contemporary world than the skyscraper,” writes Scott Johnson, M.Arch. ’75, in Tall Building: Imagining the Skyscraper (Balcony Press, $34.95). As a principal of the California architectural firm Johnson Fain, he has designed more than a few tall buildings himself.

Expedience, transcendence, ambition, and dominance: these are the principal reasons why tall buildings emerged and why they continue to be built, says Johnson. Initially, land values in places like downtown Chicago and New York City drove expansion skyward, enabled by technological developments like elevators, curtain walls, and high-strength steel.

But today, “like so much in our lives, skyscrapers have become semiotic things,” Johnson said in an interview. From San Francisco’s Transamerica Pyramid (designed by Pereira Associates, Johnson Fain’s corporate predecessor), where the final design was chosen by Transamerica’s then-CEO and ended up becoming the symbol of the company itself, to Dubai’s Burj Khalifa (formerly Burj Dubai), a national monument to modernity and global reach, tall buildings signal aspirations. Burj Khalifa, for example, at 2,717 feet, is taller than Chicago’s Sears Tower and Manhattan’s Empire State Building combined.

Johnson traces a number of the forces that have created skyscrapers, including the increasingly prosperous cities of Asia and the Middle East and the rise of mixed use. “In 1996,” he says, “eight of the 10 tallest buildings were in the United States, and only one was mixed use”--retail, recreational, office, and residential. Today, all 10 of the world’s tallest buildings are outside the United States and all of them are mixed use. “We are moving vertically to enact all the rituals and activities of our daily lives,” he explains. “Living on one floor, shopping on another, exercising, seeking open air, attending parties on others. It’s transformational.”

Bioclimatic concerns--air and light-- have been another important shaping influence in modern buildings. English architect Norman Foster has found ways to channel natural light to the very center of his buildings, while the Malaysian architect Ken Yeang gouges out his buildings’ skins to create profusely planted microclimates in sun or shade.

Just as in the 1950s and ’60s there were clear resonances between the world of architecture--with its “pure, sleek” skyscrapers--and the minimalist creations of the fine arts world, says Johnson, today the influence of the information age has reached tall buildings. In an extension of their semiotic role, their surfaces are being rethought to carry visual content and information. In certain places in city centers, their exteriors have become not only battlegrounds, but also more valuable than the space within. Johnson recounts landlord struggles with residential neighbors bothered at night by illuminated signage, on the one hand, and with tenants angered by reduced daylight after an advertising scrim is suddenly hung on the building. Recently, a developer was offered more money for the exterior of a building than the residential units inside could generate.

The fight for the exterior of tall buildings, Johnson says, is clearly the next big conversation. If we are indeed on the cusp of a new reason for building skyscrapers, Johnson’s view is that public art might play a role. “A tall building is de facto a potential work of art,” he argues. “It may be privately financed and occupied, but it is in the public realm--it is a wall of the public right of way.”