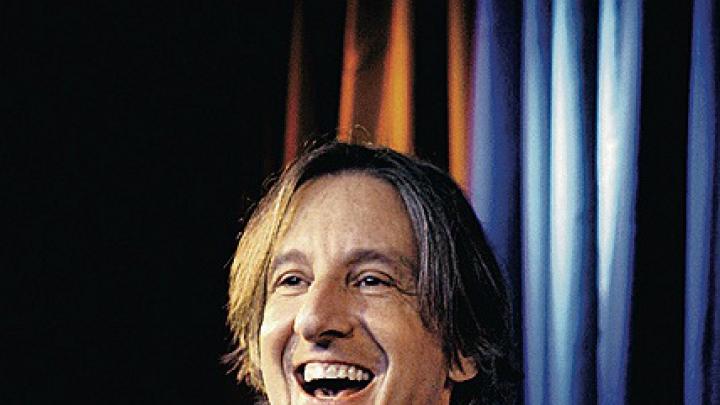

At Shaker Heights High School, outside Cleveland, Andy Borowitz '80 was the top student in his class, thanks to “extreme grade grubbing,” he says. He also became editor of The Shakerite, the school paper, whose annual April Fools' issue was filled with bogus news. "The rest of the year was tedium that you had to put up with to do the April Fools' issue," he recalls. Today, he writes and publishes the online Borowitz Report (www.borowitzreport.com), which offers, for its 250,000 readers, hilarious, preposterously false news stories, one per posting, typically playing off some topical event in politics or pop culture. "So you can see, since high school, there's been very little growth or development in my biography," Borowitz says. "The thing that bothered me in the inaugural address this year was when Obama quoted biblical scriptures that said, 'Now is the time to set aside childish things.' I took that very personally. That's not a stimulus package as far as I'm concerned-that's the destruction of my industry."

That industry includes contributions to the New Yorker's Shouts and Murmurs department and the New York Times op-ed page; newspaper syndication of the Borowitz Report; television, radio, and live appearances; a bit of film writing; five books; and even the odd bit part in a movie, like Woody Allen's Melinda and Melinda. (Ask Borowitz, "What's it like to act?" and he fires back, "I wish I knew.") All this came after 15 years of television writing and producing in Hollywood, capped by his best-known endeavor, the sitcom The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air.

The one constant is an exceptional batting average for laugh production. "Andy's at the top of the food chain in political humor," says Newsweek columnist Jonathan Alter '79, a friend since college. Carlton Cuse '81, executive producer of the television series Lost, says, "Andy is one of the funniest people I have ever known. He's smart funny-that's the potent cocktail which is so hard to find. Even if you're a jaded professional comedy writer and know all the tricks of the trade, Andy can still make you laugh because he doesn't go for the easy joke." CNN political commentator and New Yorker writer Jeffrey Toobin '82, J.D. '86, who met Borowitz in college and renewed their friendship in a green room at CNN, says, "People don't realize how demanding it is to be funny on a fixed schedule. Very few can pull it off with the metronomic consistency that he does. Andy's got a very good internal editor: he doesn't tell you 17 bad jokes and two good ones." New Yorker artist and humorist Bruce McCall sums it up: "Andy has the fastest mind of anyone I've ever met, except for Henry Beard" ['67, founder of National Lampoon].

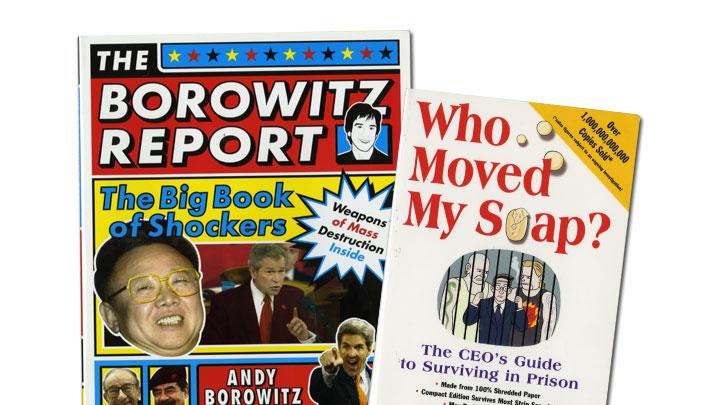

Sample Borowitz's style in this passage from Who Moved My Soap? The CEO's Guide to Surviving in Prison, his 2003 book in which the author, purportedly a convicted CEO, counsels his fellow white-collar criminals. In the chapter "Trading One Gated Community for Another," he insists that he is not writing from any soft "Club Fed" penitentiary, but from a maximum-security lockup in Lomax, Alabama:

Believe me, there's no golf course at Lomax, and when someone picks up a club, you run like hell. And riots? Last week we had a real barnburner that erupted when two prisoners got into an argument over who played the character Screech on Saved by the Bell. While no prisoners were beaten to an unrecognizable pulp in the spiraling brawl, several were beaten to a recognizable one, which, from where I sit, is just about as bad. All in all, if you think the shareholders at your last annual meeting were on a short fuse, you haven't been to Lomax.

Newsroom Haiku

Borowitz's comedic career reversed the typical pattern of writers who establish a literary reputation in New York and then migrate to Hollywood to harvest riches from the entertainment industry. Instead, he jumped from Harvard to movies and television, eventually scoring a big hit as co-creator and show runner for Fresh Prince, the series about a West Philadelphia rapper, played by Will Smith, who moves in with wealthy relatives in Los Angeles. The show, which he shaped and supervised in partnership with his ex-wife, Susan Stevenson Borowitz '81, ran from 1990 to 1996. But in 1995, at the peak of his Hollywood success, Borowitz quit and moved to Westchester County, north of New York City, and retired for a couple of years. He read, spent time with his family-which by then included daughter Alexandra and son Max-and put aside writing and ideas for new projects.

"Andy did something that almost nobody does," says Alter. "He gave up a very successful Hollywood career to hang out his shingle as a solo-practitioner humorist. He could have just minted money, made $50,000 a week in Hollywood. Instead, his income went to zero. Most don't have the guts to do that." Cuse adds that Borowitz "became a humorist-it almost sounds like an antiquated profession, but in a classic sense, that's what he is."

Fresh Prince's success made earning more income optional for Borowitz-but Alter is right: few in his position have ever made the choice he did. Nonfinancial factors figured prominently. Running a show "is creative, but also very managerial," he says. "You are dealing with so many people, balancing so many agendas. By 1996 I did not know what my voice as a writer was anymore. Groups write sitcoms. Brilliant as it is, The Simpsons sounds like The Simpsons, not like any writer's voice. The system works very well for getting a script out every week, but it doesn't feel like writing to me. It's a little like a gifted focus group being highly paid to improve a product-the script. To me, writing is something you do alone in a room, with your imagination.

"Leaving Hollywood was also a lifestyle choice," he continues. "TV is truly a young man's game, for people in their late twenties or early thirties. If you want to lead any kind of normal life, like have a marriage or raise kids, sitting in a room with rotting Chinese food at 3 a.m. trying to come up with the best line to end a scene becomes less appealing." Though Borowitz worked very hard and grew very rich in Hollywood, he looks back now and reflects that "90 percent of the things I occupied my time with never came to fruition, and of the 10 percent that did, I feel good about 10 percent of it."

Today, as a freelance humorist, he can pursue projects that "are nonprofit, either by design or de facto"-though his books, including The Trillionaire Next Door (2000), Governor Arnold (2004), The Borowitz Report (2004), and The Republican Playbook (2006) have been profitable. In writing the online Borowitz Report (see sidebar), "I have no real method," he says. Research means waking up, having coffee in bed with his wife, Olivia Gentile '96 (a journalist and author of the new biography Life List: A Woman's Quest for the World's Most Amazing Birds), and watching the news.

"I tend to be on top of only the one or two biggest stories of the day," he says. "Then my mind wanders to some take on that material. Sometimes it's just stating the truth very baldly [Obama Poised to Become Most Ass-Kissed President Ever]-Mark Twain said you can't really improve on the truth. Sometimes it's exaggerating or amping up the truth to an extreme [Bush to Phase Out Environment by 2004/All Species Under Review, President Says]. Sometimes it's politicians saying exactly what's on their mind, which they would never do in real life [Palin Blames Daughter's Pregnancy on Media/Demands Media Marry Bristol]. Having written thousands of these columns now, it's more like muscle memory than an intellectual process." Alter observes that the columns are "not just funny on their own terms, but are a send-up of journalistic conventions. Basically, Andy uses a very strict AP form-it's almost like he's writing newsroom haiku."

When he launched the Borowitz Report in 2001, "No one was reading it-it was a sinkhole for money," Borowitz says. "Hundreds of dollars were thrown away. When I saw my stats, I'd be thrilled to find that three people were on the site." Word of mouth expanded his audience, which then jumped dramatically when the Wall Street Journal did a front-page story about him in 2003; thousands of aspiring subscribers crashed the site. He accepts no advertising, because "advertisers would have the right to approach me and say, 'We didn't like that.'" Syndicating the column to a few dozen newspapers does make some money, and he uses the site to promote his own books and appearances. "If you're in the business of marketing Andy Borowitz," he explains, "I have the perfect listserv."

Offended readers sometimes cancel their subscriptions. "I want to say to them, 'I would take that very hard if you were actually paying me something for your subscription,'" he says. "But I don't know what kind of threat that is, since I'm essentially spamming you. That's one of the keys to the success of the Borowitz Report: don't charge anything for it." At first Borowitz wrote new columns daily, then took weekends off. Now he posts two or three fresh satires each week. "I think I love it even more now," he says. "I write when a story really appeals to me. I'm getting a kick out of it."

His short comic arias for the New Yorker began in 1998; editor Susan Morrison '82 called while he was working in the garden and asked if he had any funny ideas on Bill Clinton's scheduled deposition for the Monica Lewinsky case. Borowitz confected a series of talking points for Clinton, "basically a lot of elaborate ways to explain how sperm got on her dress." It ran the week that David Remnick became the magazine's editor, and 11 years later, Borowitz is still contributing.

Literary humor differs structurally from composing a TV comedy script, which has actors, directors, and technical crew all contributing to the end product. "On the page, there's a disadvantage in that no one is helping you," Borowitz explains. "But there's also an advantage, because you're communicating directly with the reader. A lot of times, in a film or TV show, there might be something that was hilarious on the page, but when it gets staged, somebody's wearing the wrong costume and that throws off a joke, or somebody does a gesture that's not right-there are a lot of perils in performance. With the page, and especially the Internet, it's almost like you're communicating this message just between you and the person who's reading it-very unobstructed, a kind of closed circuit."

The talent for creating risible content, though, is a largely inexplicable gift. Borowitz has been asked to teach humor writing classes and has even tried it a couple of times, but no longer does so because "I feel like it's a scam-you can't really teach somebody how to do it. People are either funny or not; it's very hard to boil it down to a formula." Certain old sayings, like "Keep it short," do apply: "Any joke is better if you can remove some words." He says he just tries "to find the thing that cracks me up, and hope other like-minded people will laugh." Sometimes he field-tests a joke on his wife ("Livy is extremely supportive, but she's also very discerning. Unfortunately.").

In recent years, Borowitz has been breaking up audiences as a live performer, joining forces with comedian Mike Birbiglia, star of the one-man off-Broadway show Sleepwalk with Me, for example. "Andy just picked up stand-up comedy as a hobby," Birbiglia says, "and he's as good at it as anybody." This is all the more astonishing, he adds, because stand-up "is such an uphill battle, such a soul-crushing endeavor." Borowitz notes, "To a lot of people, voluntarily doing stand-up comedy is a psychiatric disorder that's probably in DSM-IV." Often, he operates in improv mode, taking questions from an audience and riffing off them. "When the audience is in the same room with a comedian when a joke is being created," he says, "there's an extra excitement in that moment.

"We live in a culture now where our entertainment has had all the edges taken off," he continues. "Everything has been sanded down; it looks so polished. We have special effects and lighting that can make everybody look perfect-and we sweeten the shows so that the sound is perfect and the applause is perfect. Most of the entertainment we get now has been so refined and so packaged that the spontaneity has disappeared." Consequently, he feels, there's a hunger for alternatives like The Moth, the nonprofit, Manhattan-based storytelling group (www.themoth.org) that puts on live storytelling evenings (sometimes with Borowitz as emcee and performer) that are podcast.

"There's this very primal thing of a person standing in front of an audience telling a story," Borowitz says. "It's like being around a campfire. Things will go wrong, people will lose their way, they'll forget what they're going to say, maybe they screw up the verb tenses. At Moth Slams we pull names out of a hat, and the performers come out of the audience. Sometimes they're brilliant and sometimes they're horrible, but to go from brilliant to horrible and back again in the same night is kind of fun, too. Raggedness is what's missing from the culture. I've found that there's a place for the spontaneous and the ragged, and that's what I'm enjoying."

The Fresh Prince of Shaker Heights

Intellectually speaking, the Borowitz family of Cleveland burns brightly. Father Albert Borowitz '51, A.M. '53, J.D. '56, graduated summa cum laude and is a multilingual corporate lawyer, now retired, who has published more than a dozen books of true-crime history, many art-related. Mother Helen Osterman Borowitz '50, an author and art historian, was a curator at the Cleveland Museum of Art. First-born son Peter Borowitz '75, J.D. '78, zipped through Harvard in three years, also graduated summa, and is now retired from the New York law firm Debevoise & Plimpton, where he was a corporate bankruptcy partner. Middle child Joan Borowitz, a Simmons College alumna, has worked in hospital administration.

Andy, the youngest, grew up "a very solitary kid" who sat at a desk and wrote comic books or spoofs of detective novels while his dad wrote about real crime. "In my family I was the little one, and birth order is such a key thing in families," Borowitz says. "The little kid becomes intrinsically funny because he's the littlest and kind of cute compared to the bigger kids. Left to my own devices, I learned how to use my imagination to entertain myself. It also resulted in an outsize need for attention. Normal people don't really want to get up on a stage and try to make people laugh."

Though he was tall-today, Borowitz stands six feet, five inches-he was a scrawny youngster who tipped the scales at only 87 pounds in seventh grade. He wasn't gifted in sports, but sang and played guitar and keyboard in high school. He also made Super 8 movies, often starring his brother. ("I was the first star he created," says Peter. "Will Smith followed in my footsteps.") The young Borowitz was "a bourgeois class clown," he says. "No one is more bourgeois than I am. I was never sent to detention. I've never been an artist trying to bring down society from my garret."

When Borowitz was a student, Shaker Heights High School also drew from Cleveland neighborhoods; enrollment was 40 percent African American. "It's not that I understood the black experience," he says. "But having grown up with a lot of black kids, I've never had the discomfort that many white people have when in a room full of black people. When we started working on Fresh Prince in 1990, I always felt at ease with Will Smith and the other black actors, and comfortable asking questions, trying to understand the black family."

At Harvard's freshman orientation, the former Shakerite editor took a flyer advertising a comp meeting at the Crimson. He and the others who showed up soon learned that there was no meeting that night; the flyer was a hoax, courtesy of the Harvard Lampoon. "So my first encounter with the Lampoon was being pranked by them," he says. Nonetheless, he comped the Lampoon successfully as a freshman and by senior year was its president. "Harvard doesn't have many BMOCs, but Andy was a very recognizable figure, even as an undergraduate," says Jeffrey Toobin. "He's tall and is blessed with one of the most memorable noses in show business."

As a sophomore, Borowitz wrote A Thousand Clones, the first futuristic Hasty Pudding show, and the next year, with his roommate, pianist Fred Barton '80, put on Not Necessarily in That Order, a songs-and-sketches revue in Adams House. "It was just a bunch of us with no supervision and no money, trying to be funny," he recalls. "Musicals in the Houses then were charging $5 or $6 a ticket. We decided to charge $1 a ticket, and we had to turn people away. It was the first time I'd seen a connection between entertainment value and popularity."

The summer before his senior year, Borowitz led a Lampoon team in mailing a parody of the Crimson's initiation issue to all incoming freshmen. "The idea was to make Harvard look emotionally unsettling and even physically dangerous," Borowitz recalls. "There was a story of a cafeteria worker accused of putting ground glass into the food, and an exposed third rail in Harvard Square that had killed a few students. The main headline was 'Class of 1983 Smartest Ever,' with dean of freshmen Henry Moses noting that most of the incoming freshmen already had college credits-those who didn't should not feel bad, but 'They have a good year of catching up to do.' Incoming freshmen were required to have read either Remembrance of Things Past, Finnegans Wake, or Taurus Rising by Joan Didion, a book that does not exist. Freshman parents were calling University Hall trying to get their deposits back. It was a highly successful prank that created maximum havoc."

In Borowitz's junior year, television producer Norman Lear came to the Lampoon Castle to accept an award; the following fall, Lear's partner Bud Yorkin screened a film comedy they had produced, Start the Revolution Without Me, at the Science Center. Borowitz introduced Yorkin with 10 minutes of stand-up comedy, working off the conceit that he had actually orchestrated Yorkin's career. Later, at the castle, Yorkin received a "Golden Jester Award," an honor never bestowed before or since.

Thanks largely to that stand-up performance, Yorkin offered Borowitz a writing job. Borowitz was applying for fellowships; his parents wanted him to be a lawyer, but the English concentrator never seriously pursued that path. "The night Bud offered me the job," he says, "my first thought was, 'Now I don't have to finish that Rhodes application.'"

Two weeks after graduation, he and friend and fellow Lampoon member John Bowman '80, M.B.A. '85, drove cross-country in a 1975 Buick Skyhawk provided by the former's parents. "We planned our route according to where Motel 6s were located," Borowitz says. His first day working for Yorkin, the producer gave him a scene from a screenplay to rewrite. "Not knowing enough to be terrified, or whether it was a test or a hazing, I just did it and handed it in to the secretary to type up," Borowitz recalls. "Bud thought it was great, and took me to lunch at Morton's. He told me there were two kinds of people, 'doers and viewers.' I was a doer."

He also wrote an original screenplay, The Bottom Line, for Yorkin, a comedy about a new college graduate who is rapidly promoted at a company seeking a fall guy for an impending business debacle. The film, though optioned several times, was never made, but the script served as a calling card that got Borowitz more work in film and television writing.

Dissatisfied with the glacial pace of the movie business, Borowitz asked to work on the television side of the company. He wrote for Archie Bunker's Place, Square Pegs, The Facts of Life, and other sitcoms throughout the 1980s. "Andy was on the front edge of that wave of writers who emigrated from Harvard to Hollywood, especially to television," says Carlton Cuse. "There was hardly any footpath between those two worlds before Andy forged one."

During the 1980s he also worked on Little Gentlemen (later Young Bucks), a screenplay about preppies based on a concept by Doug Kenney '68, the Animal House and Caddyshack writer who perished shortly after Borowitz arrived in Los Angeles (see "The Life of the Party," September-October 1993, page 36 [download a PDF (7.6 MB)]). Borowitz collaborated on the script with Kenney's partner at the National Lampoon, Henry Beard; they made "a ton of money" revising a screenplay that was never made, Beard says. A story editor at Warner Brothers noted, "This is the best first draft I've ever read," but, Borowitz adds, "We rewrote it about 18 times and each draft got a little worse."

In the late 1980s, Borowitz had a deal at NBC to develop sitcoms; the network brought him a nascent project called The Fresh Prince, starring the then-unknown Will Smith in the title role. Hedging its bets, NBC didn't commission a full-scale pilot, only a 19-minute "presentation," using sets from a defunct soap opera. "But Will Smith, in front of the audience, just exploded," Borowitz says. "I've never seen another performer have that kind of love affair with an audience-he was just so magnetic."

The "bell-ringing moment" that coalesced the show's premise came at the Bel-Air mansion of Quincy Jones, D.Mus. '97, the music producer who had brought Smith to Hollywood. Jones began telling stories about his African-American children growing up amid the affluence of Bel-Air. One daughter had called home from summer camp and left a message: "Dad, the water here sucks. Please Fed-Ex some Evian." "That was what made it click for me," Borowitz explains, "because if you take somebody like Will, from West Philadelphia, and put him in a family like Quincy's-that's a show."

Indeed it was. The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air became a household name, won the NAACP's Image Award for Outstanding Comedy Series in 1993, made Smith a star, and allowed Borowitz to segue into his current many-faceted life. He hasn't left Hollywood completely behind: he and his ex-wife, Susan (they married in 1982 and separated in 2005), were executive producers of Pleasantville, the thought-provoking 1998 film comedy, and he is one of the screenwriters on Dinner for Schmucks, an adaptation of a 1998 French movie due for release in 2011.

Now he is writing his first novel ("I'm keeping my fingers crossed that there will still be publishers when it's done"), and relishing the life of a dilettante humorist in New York: performances with The Moth and at the 92nd Street Y, plus occasional corporate or college dates; random guest appearances on CNN or MSNBC with Keith Olbermann, or on National Public Radio's Weekend Edition; watching sports with his son; or playing on the New Yorker's softball team ("I'm posted as far away from the ball as possible"). When called on, he enjoys his bit parts in movies. "The appealing thing about acting is, you don't have to make up anything you say," he confides. "It almost feels like being waited on."

Guest appearances suit Borowitz's lifestyle, because he likes to be home a lot. "Andy is like an overgrown 14-year-old boy, in the absolute best sense," says his wife, Olivia. "He takes pleasure in so many things that most adults don't let themselves enjoy, like playing video games. He's a Midwesterner who's kept his innocence and his small-town values. He's extremely Zen and not very career-oriented; Andy is more interested in living each day well."

Last fall, Borowitz's life went through a refiner's fire when he underwent three surgeries for a twisted colon, the second on an emergency basis. After the first operation, his colon became perforated, and his chances of survival were, at one point, no better than even. "I almost died twice," he says. Although he is now in fine health, the experience was "very harrowing, and it only served to reinforce the decisions I had already made: to do the things that are most rewarding and spend time with the people who are most rewarding." Even in his hospital room, though, on his laptop, he continued to crank out takes on the final stages of the presidential campaign, and to break up his friends with throwaway lines: "Abdominal surgery," he observed, "is not as much fun as the media make it out to be."