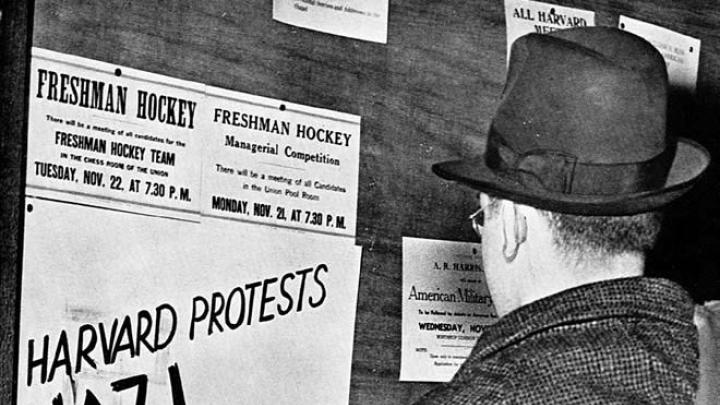

At noon on November 16, 1938, some 500 Harvard and Radcliffe students jammed Emerson Hall to express their outrage at Kristallnacht, as the Nazis sarcastically dubbed the pogrom in Germany and Austria that had littered the streets with broken glass. But that lunch-time gathering turned out to be much more than a student pro test meeting. Besides starting an initiative that eventually brought 14 young refugees from Germany, Austria, and Czechoslovakia to study at Harvard—and two refugees, in a parallel effort, to Radcliffe—it gave rise, with astonishing speed, to a national grassroots movement that helped hundreds of persecuted Central European students find refuge and education at colleges and universities across the United States. Though now largely forgotten, the humanitarian effort that emanated from Harvard highlights a tectonic change among many students at the time—from ivory-tower existence to social activism. And the story also illuminates a gradual transformation of Harvard and other leading colleges: from institutions that educated mainly the children of the elite to institutions that prized scholarly excellence. Now, as the generation of activists who led that effort is passing from the scene, it seems worthwhile to recall their story, especially as today’s students consider engaging in larger issues—among them, again, immigration.

The initial response

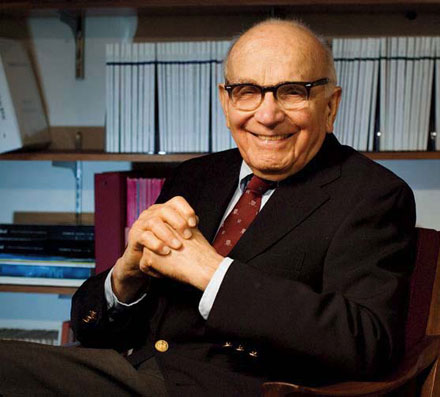

Many of the students crowding Emerson D that Wednesday felt strongly that Kristallnacht called for action, not merely protest. “The link between thought and action among students is natural and visceral,” says Robert E. Lane ’39, remembering his undergraduate years. Now a Yale professor emeritus, Lane was president of the Harvard Student Union that fall. The union’s motto was “Think as men of action; act as men of thought,” and Lane (who in 1938 was also national chairman of the American Student Union) was already a veteran of activism against General Francisco Franco’s uprising in Spain and the Japanese invasion of China. (Closer to home, he had “recently been scolded by the Harvard Treasurer for seeking to organize the waitresses in the House dining halls, on the grounds that the profit made by the dining halls was dedicated to the scholarships of [his] own friends!”)

|

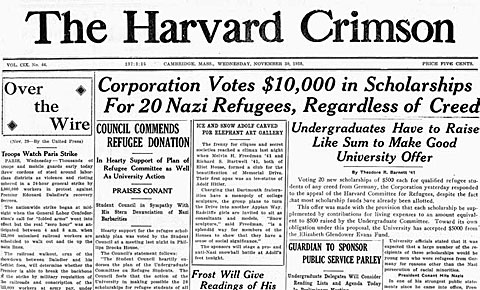

The Harvard Crimson |

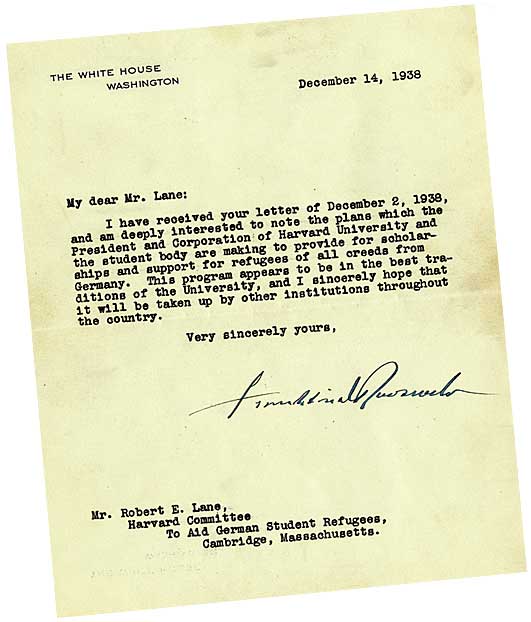

The Nazis’ Kristallnacht pogrom in 1938 prompted Harvard student activists to devise a way to rescue endangered European students. The Harvard Yearbook (top)and Crimson covered their fellow students’ efforts; a famous alumnus offered encouragement (below). |

|

Courtesy of Gerhard Sonnert and Gerald Holton |

Lane’s position made him a leader within the ad hoc committee that organized the Emerson Hall meeting. His fellow members represented 10 other undergraduate groups, among them the Council of Government Concentrators, Phillips Brooks House, the St. Paul Society (Catholic), and the Avukah Society (Jewish). The invited speakers, who denounced the Nazis and urged American aid for their victims, included Divinity School dean Willard Sperry as well as professors Zechariah Chafee Jr. of the Law School and Carl J. Friedrich of the government department. The latter, according to the Crimson, inserted a practical note into the meeting: “We do need charity; let us add a little bit of intelligent planning.”

Acting swiftly and skillfully, the students created a formal organization, the Harvard Committee to Aid German Student Refugees, within three days of the Emerson meeting. Before approaching President James Bryant Conant in an attempt to involve the University in their plan, the group met with dean of Harvard College A.C. Hanford, who would serve as a crucial intermediary. After Hanford explained that most scholarship money had already been distributed for the year, the young organizers formulated a plan for 20 refugee students to come to Harvard: the Corporation would be asked to cover their tuition, and the undergraduate committee would provide for their living expenses through a campaign aimed at raising $10,000 from fellow students and $25,000 from faculty, staff members, and alumni.

On Friday, November 25, a small delegation led by Lane that included Avukah president Irving London ’39 (M.D. ’43, today a professor at Harvard and MIT), the committee’s secretary-treasurer, Philip Bagby Jr. ’39, and Abba Schwartz, a third-year law student who chaired that school’s refugee committee, called on Conant, who may well have been briefed by Dean Hanford. From Lane’s perspective as Student Union president, “The University administration was a kind of paternalistic opposition with whom we were constantly engaged in more or less friendly combat,” he recalls. “They were sometimes our allies, but we had to be wary. We were the loyal opposition.…We went to Conant’s office in a mood of nervous preparation for engagement.î Now the students had come to ask permission for their own fundraiser, and to express the hope the University would do its part. Irving London remembers that the president greeted them ìvery coolly, I would say. We couldn’t read his face,î but that eventually Conant indicated that the administration would ìmatch you dollar for dollar.î ìWe were,î London recalls, ìon cloud nine.î †

Meanwhile at Radcliffe, a smaller and more informal but speedy student effort had kicked into action. Tables were set up and placards displayed to collect money for the cause, recalls Lucille Radlo Gray ’39, who led the Avukah chapter there. Radcliffe president Ada Comstock had already promised to cover tuition for any refugee students whose room and board the undergraduates could underwrite, so that Sunday the students ate hash instead of steak and gave up their usual ice-cream dessert, saving $95 that was added to the fund.

Gathering energy

“Corporation votes $10,000 in Scholarships for 20 Nazi Refugees, Regardless of Creed,” the Crimson announced on November 30. (Half the amount had reportedly been donated by Boston philanthropist Elizabeth Glendower Evans, a former suffragist and recent national director of the American Civil Liberties Union.) That evening the Student Council “heartily endorse[d]” the refugee-student plan—the first time, reported the Crimson, that the council had joined in sponsoring any kind of student movement.

President Conant, who had expressed no personal convictions at the start of his formal meeting with the committee, now issued a ringing endorsement of their work and suggested expanding the movement as well:

The endeavor of the Harvard College students to raise money by their own efforts to aid refugees is of importance primarily as a symbol of the determination of the younger generation to show by deeds as well as by words that the humanitarian basis of democracy is not dead. If similar organizations in other colleges and universities can raise funds to take care of capable students who are fleeing the terrors of dictatorship, it will be evident that the American youth has not been made callous by the ruthlessness of the Russian experiment or the barbarities of the present German government.

The Corporation’s decision generated national publicity. A New York Times editorial praised Harvard’s action as an effort to further academic freedom and scholarship, and also anticipated the criticism that humanitarian aims might trump academic standards. Besides suggesting that the refugee students sought by Harvard would be mature and academically qualified, the Times alluded to a sentimentóexpressed in much of the committee’s literatureóthat the young refugees ìwill give more than they receive.î The editorial invoked a cross-cultural exchange through which American universities would benefit from the scholarship and the experience of European refugees. A Crimson editorial published the day the Corporation met had noted the same: ìHarvard will gain, in addition to the satisfaction of having tangibly asserted her belief in human values, a score of brilliant minds, qualified to carry her standards to higher levels.î

The students’ movement thus had developed in short order three interconnected purposes: the humanitarian goal of rescuing individuals whose education was interrupted and whose lives were in jeopardy; the political goal of a∞rming American core values of tolerance and democracy; and the academic goal of improving the quality of higher education.

To achieve those goals, the committee tackled multiple challenges. It continued to recruit more undergraduate groups as allies and enlist faculty sponsors. One of the most influential was Law School professor (and soon associate justice of the Supreme Court) Felix Frankfurter. Just as Hanford proved to be a sympathetic intermediary between the students and Harvard’s administration, so Frankfurter, a long-time friend of President Franklin D. Roosevelt, would act as an intermediary between the students and the U.S. government. Some members obtained endorsements from celebrities such as Helen Hayes. Albert Einstein sent a telegram: “Appreciate greatly your generous effort as aid in emergency and as humanitarian attitude.” In December, messages of support arrived from New York governor Herbert Lehman and from President Roosevelt, who wrote, “This program appears to be in the best traditions of the University, and I sincerely hope that it will be taken up by other institutions throughout the country.” (That letter, Lane recalls, was “always at hand” as the undergraduates attempted to tap the resources of New York’s vast social network.) Other members handled the details of preparing and circulating an application blank for potential scholars. Fundraising was a huge task. Supportive House committee members agreed to collect money and pledges on sheets labeled “Harvard’s Book for Religious, Racial, and Political Tolerance” at the entrance of the dining halls. But the single largest event planned was a mass meeting at Sanders Theatre on December 6, meant in part to attract students from other Boston-area colleges.

That night, the theater was jammed. Football team captain Robert Green chaired the meeting; the featured speakers included Lane, Hanford, Massachusetts governor-elect Leverett Saltonstall [’14, LL.B. ’17], and comedian Eddie Cantor, who also made a sizable donation. Irving London remembers “mixed feelings about having Eddie Cantor. But he was glad to come…and he was very effective: he was very funny, but he was serious at the same time. That was the kickoff for the money-gathering” at the College. “Remember, the Depression was still with us. Extra money was really scarce. There were some wealthy people, but a lot of the students were just making it. So we were very impressed with what they did.” Months later, an essay by seniors William Chambers and Frank Davidson in the 1939 class album declared the Sanders meeting “the grand wake for an ancient and much-touted institution, Harvard indifference.…It marked a trend—the rise of organizations for action as a fixed part of the life of Harvard….”

Going national

On the same day that the student committee’s delegation met with President Conant, sophomore Robert B. Ridder ’41, a fellow member, was in New York, visiting the International Student Service (ISS; a student-exchange organization) to discuss duplicating the Harvard refugee effort on a national scale—even before the project had been o∞cially sanctioned at Harvard. The first result of this expansion effort was an “Intercollegiate Conference” planned by Lane, Bagby, and Schwartz. Just six weeks after the initial Emerson Hall meeting, some 100 colleges and universities sent delegates to the December 27 conference in New York City that created the Intercollegiate Committee to Aid Student Refugees (IC). The initial rent for the IC’s New York o∞ce was paid by Ingrid Warburg, herself a refugee student from Germany. A relative of the wealthy banking family, “she was always there when we needed her,” Robert Lane remembers. “She brought a kind of tempered wisdom to our efforts.”

In rather a daring move, Lane soon disappeared to New York for most of the spring semester of his senior year to chair the IC. (Dean Hanford informed him that the College could not o∞cially condone his extended absence, but also indicated that it would, in effect, tolerate it. In order to graduate, Lane explained years later, he asked a Cambridge tutoring agency for a contribution in kind to the refugee committee: “They agreed and saw me through my exams.”) By March 1939, the IC reported, more than 170 colleges in 39 states were actively involved, with 214 scholarships granted and room and board provided; the number of colleges eventually reached 213.

That September, the IC formally merged with ISS, with Lane and its other leaders becoming members of the ISS executive committee. In less than one year, a spontaneous, grassroots student movement had matured and been absorbed into a preexisting international organization.

Framing the debate

But the refugee initiative also had detractors among alumni and the general public. Anti-Semitism was a major factor in opposing the admission of Jewish refugees to American colleges, but not the only one. Some critics, arguing from an isolationist perspective, questioned what they perceived as a double standard: helping refugees from National Socialism while ignoring those from other trouble-spots around the globe. Others charged that the poverty and hardship caused by the Depression made it inappropriate for Harvard and other universities to grant scholarships to foreigners. In response, Hanford emphasized that the refugee plan was student-directed, spontaneous, and humanitarian in character; he also explained that Conant’s recently inaugurated and much more numerous National Scholarships were designed to target students mostly from the Midwest or West who could not finance their own Harvard educations.

Relatively few outside critics raised concerns about the academic caliber of the refugee students. At Harvard itself, on the other hand, the definition of merit had been tentatively moving from what was called character (which was partly code for coming from the “right” families and prep schools) toward referring to a record and promise of academic accomplishment (a concept also fraught with ambiguities). This shift toward a meritocracy governed by scholarly excellence began under Conant, who had publicly worried about “the curse of complacent mediocrity” that might threaten universities like Harvard. The defenders of the refugee-student initiative thus went to some lengths to argue that the foreign arrivals would not drag down Harvard’s academic average. The extensive inquiries on the refugee-scholarship application blank demonstrated how important evidence of academic achievements had become.

Obstacles and progress

Despite the initiative’s promising start, and the fears of its critics, fewer European students than the activists desired reached this country. Perhaps no issue was more troublesome to the refugee organizers than immigration regulations and visas. It was one thing to identify, admit, and fund accomplished students for study at Harvard or other American universities. It was an altogether different matter for those admitted students who were still in Europe to actually enter the United States, owing to difficulties in Europe, to problems with U.S. immigration regulations, or both. The main problem was that the U.S. government usually did not want to grant visas to students who would be unable to return home after completing their degrees.

Here the initiative hit a formidable obstacle, with two apparent consequences for the program at Harvard. Of necessity, attention now focused more on young refugees already in this country. And even so, only 14 of the 20 slots available at Harvard could be filled.

Nonetheless, there were triumphs. According to the Crimson, the selection committee processed some 170 applications and determined that all the scholarship recipients “have had scholastic records abroad equivalent to Dean’s list at Harvard.” The first two recipients—Karl Deutsch and Kurt Hertzfeld—matriculated in the spring of 1939 (in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences and in the College, respectively). Of the remaining 12 scholars, five were undergraduates, one attended the Medical School, and the rest enrolled in the graduate school. At Radcliffe, Rahel Kestenberg of Prague arrived on February 13; the friend of an English graduate student, she entered as a junior, concentrating in American history and psychology. Another refugee student, Regula Frankl (Davis), entered as a freshman that semester; she had been in the United States for some time.

The refugees’ careers at Harvard and beyond proved impressive, with many of them achieving doctorates in various fields (see below). Kurt Hertzfeld ’41, M.B.A. ’42, was elected to Phi Beta Kappa. (He had to borrow money to buy his key.) An Austrian immigrant, he had been supporting himself in New York as a dry-cleaner’s delivery boy when he chanced to see an article about the scholarships in the Times. After a career in business, he would become treasurer of Boston University. Indeed, compared with their Harvard classmates, the refugees’ eventual careers tilted toward the academic. Klemens von Klemperer, A.M. ’40, Ph.D. ’49, for example, became a professor of history at Smith College and made the study of the resistance to National Socialism a major part of his life’s work. Karl Deutsch, A.M. ’41, Ph.D. ’51, later Stanfield professor of international peace at Harvard, the most famous of the former refugee scholars, became one the foremost political scientists of the twentieth century.

Reunion

Despite its successes, the Harvard student initiative was soon forgotten. Most of its leaders graduated in June 1939, months before the majority of the refugees arrived in September. Many refugee students had no clear idea of the activities that had created their scholarships. Walter Pick, M.D. ’42, for example, who left Czechoslovakia for Cambridgeas soon as he learned he had won a fellowship—escaping arrest by the Gestapo only by hours, as he found out much later—became friends with fellow Harvard Medical School student Irving London without either knowing of their refugee-committee connection.

But in 1989, half a century later, former refugee student George Rohrlich, Ph.D. ’43, began planning a reunion of his fellows and of the committee organizers at Harvard to recognize the original activists. Early in June 1990, eight former refugee scholars and three members of the refugee-committee gathered in celebration. As part of the program, and in the presence of then-president Derek Bok and dean of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences Henry Rosovsky, a commemorative linden tree was planted near Boylston Hall in Harvard Yard. The bronze plaque embedded in the ground beneath the tree reads: “To Harvard University Students – Faculty – Staff – Alumni – whose generosity fifty years ago opened doors to Student Refugees from Nazi Persecution. May this tree express in grace and beauty the abiding and heartfelt gratitude of the recipients.”

Harvard Yearbook | Robert E. Lane ’39, Ph.D. ’50, then president of the Harvard Student Union, helped spearhead the committee to aid refugee students. |

| Irving London ’39, M.D. ’43, then president of the Avukah Society, a Jewish student group, helped Lane win Harvard administrators’ aid. |  |

| |

| Irving London ’39, M.D. ’43 | |

| Photograph by Jim Harrison | |

In supporting these refugee students, Harvard did well by doing good. The later achievements of the former refugee students confirmed the prediction in the Intercollegiate Committee’s pamphlet The Student Refugee Problem: that for “the youth in the fascist countries,” rescued or aided as they were by the work of the concerned students of 1938-39, “there can be no doubt that they will contribute richly to the culture of whatever country offers them a home.”

Gerhard Sonnert, M.P.A. ’88, Ph.D., is a sociologist of science and a research associate in the physics department. Gerald Holton, Ph.D. ’48, is Mallinckrodt Research Professor of physics and Research Professor of history of science. Their book What Happened to the Children Who Fled Nazi Persecution, presenting a detailed analysis of the larger stream of young refugees from Central Europe to the United States, is scheduled to be published by Palgrave Macmillan in December. They wish to acknowledge the fine archival work and excellent contributions of their faculty aide, Frederic Nolan Clark ’08, who helped prepare this article.

Harvard Refugee Scholars—Country of Origin—Career Fields and Major Professional Positions

Ernst Berliner, M.A. ’41, Ph.D. ’43—Germany—Professor of Chemistry, Bryn Mawr

Karl Deutsch, Ph.D. ’51—Czechoslovakia—Professor of Government, Harvard

Kurt Hertzfeld ’41, M.B.A. ’42—Austria—Business; Treasurer, Amherst College and Boston University

Hans Imhof ’42—Austria—Officer, U.S. Legation, Vienna

Herman Noether, M.A. ’40, Ph.D. ’43—Germany—Chemical Researcher, Celanese Corp.

Walter Pick, M.D. ’42—Czechoslovakia—Chief of Pediatrics, Burbank Hospital, Fitchburg, Massachusetts

Walter Robichek ’42, M.P.A. ’44—Czechoslovakia—Regional Director (Western Hemisphere), International Monetary Fund

George Rohrlich, Ph.D. ’43—Austria—Economist, U.S. Social Security Administration; Professor of Economics—Temple University

Milos Safranek ’42—Czechoslovakia—Adviser, International Civil Aviation Organization

Herbert Sonthoff, M.A. ’42—Germany—Railroad Director and Acting City Manager

George Springer ’42, Ph.D. ’54—Czechoslovakia—Dean of the Graduate School, University of New Mexico; Professor of Anthropology

Walter Stettner, Ph.D. ’44—Austria—Officer, U.S. Foreign Service

Klemens von Klemperer, M.A. ’40, Ph.D. ’49—Austria—Professor of History, Smith College

Thomas Winner ’42, M.A. ’43, Ph.D. ’50 (Columbia)—Czechoslovakia—Professor of Slavic Languages and Comparative Literatures, Brown University; Director, Program in Semiotic Studies, Boston University

Radcliffe Refugee Scholars—Country of Origin—Career Fields and Major Professional Positions

Regula Frankl (Davis) ’42—Germany—Assistant Editor, Physics Today (publication of American Institute of Physics)

Rachel Kestenberg ’40—Czechoslovakia—(Still being researched)

Leading Harvard Student Organizers—Position in Student Committees

Philip Bagby ’39—Secretary (1938-9)—Officer, U.S. Foreign Service (later studied at Oxford University)—Charles Ennis ’40, LL.B ’48 (Cornell)—Chair (1939-40)—Lawyer, Private Practice

Robert Lane ’39, Ph.D. ’50—Chair (1938-9)—Professor of Political Science, Yale University

Irving London ’39, M.D. ’43—Rep. of New England Avukah Society—Professor of Medicine, Harvard; Professor of Health Sciences and Technology, and of Biology, MIT; Founding Director, Harvard-MIT Division of Health Sciences and Technology

Robert Ridder ’41—Chair, Contact Committee (1938-9)—Chairman, WCCO Radio and Television

Abba Schwartz, LL.B. ’39—Chair of Law School Refugee Committee—Assistant Secretary of State, Security and Consular Affairs

Leading Radcliffe Student OrganizersóPosition in Student Committees

Alice Burke ’39—Chair—Reporter, Boston Herald

Lucille Radlo (Gray) ’39, M.S.W. ’41 (Simmons)—Business Manager—Social Worker