Adapted by the author from the Convocation Address she delivered to the Divinity School community on September 19, 2005, at the opening of the academic year, half a century after the first female students matriculated there.

The admission of women to Harvard programs——a contentious question across the University——raised a particularly challenging set of questions and possibilities at the Divinity School (HDS). Many of the religious groups for whom the school trained clergy viewed women as incapable of ordained ministry. Nonetheless, when the first such proposal came from a group of the school’s graduates in 1893, the committee charged to respond noted, “There are many women now preaching in various denominations and it is clearly of importance that such women should receive adequate instruction before entering the ministry.” Even so, committee members found it “unwise and impracticable” to grant the petition because “in many courses graduates and undergraduates of the college outnumber the Divinity School men—in some courses forming a very large proportion of the class.”

This was enough to doom the proposal, because the undesirability of women in College courses was then the central pillar of Harvard’s policies toward women’s education. It dictated the novel form of “the Annex,” later known as Radcliffe College, in which women heard the same lectures, delivered by the same faculty members, as Harvard men, but at different times and places. Charles William Eliot, the president who transformed Harvard between 1869 and 1909 from a strong regional college into a world leader, was firm on this issue. He opposed the presence of women in Harvard classrooms precisely because he wanted to broaden the pool of men available to the academic meritocracy, including—with limits—the sons of immigrants, non-Christians, and Catholics. “[C]oeducation does very well in communities where persons are more on an equality,” he told the wife of a founding trustee of Johns Hopkins, “but in a large city where persons of all classes are thrown together, it works badly, unpleasant associations are formed, and disastrous marriages often result.” Coeducation might be all right where students shared a single faith, as with Methodism at Boston University, but not at an institution where, thanks to the elective system inspired by Eliot’s Unitarian rationalism, young minds were free to explore. Broad and Emersonian in outlook, Eliot made Harvard one of the first universities to abolish mandatory chapel, and helped the Divinity School live up to the nonsectarian principles on which it had been founded.

Eliot unburdened himself on the topic of women’s education at the inauguration of Caroline Hazard as president of Wellesley College in 1899. In the audience sat M. Carey Thomas, the Quaker president of Bryn Mawr, bedecked in academic regalia. Eliot’s speech, she recalled, “made me hot from head to foot.” He described the education of women as an experiment, wondering aloud about women’s intellectual capacities and about the ability of women’s colleges to inculcate good manners while providing an education that would not injure women’s “bodily powers and functions” [see “The Great Debate,” November-December 1999, page 56].

When gender entered the picture, Eliot’s views of the role of religion in education changed entirely. Harvard men, Eliot believed, in both the College and the Divinity School, should be free to worship or not as their consciences dictated, and should take an historical approach to the study of religion. The University should impart knowledge and foster moral development, so that the individual could choose the right. Wellesley women, in contrast, should have their “religious motives and aspirations” shaped by their college, and particularly by the “simplicity, dignity, and intellectual strenuousness of Congregational worship…where …‘vain repetitions’ are avoided, and the gregarious religious excitement so unwholesome for young women finds no place.” This gendered dynamic, in which the practice of religion, the continuity of tradition, and the benefits of religious authority are associated with women for whom higher education may be injurious, whereas the critical study of religion is associated with men for whom its practice is a private matter, provides an important backdrop for understanding what would transpire in subsequent decades.

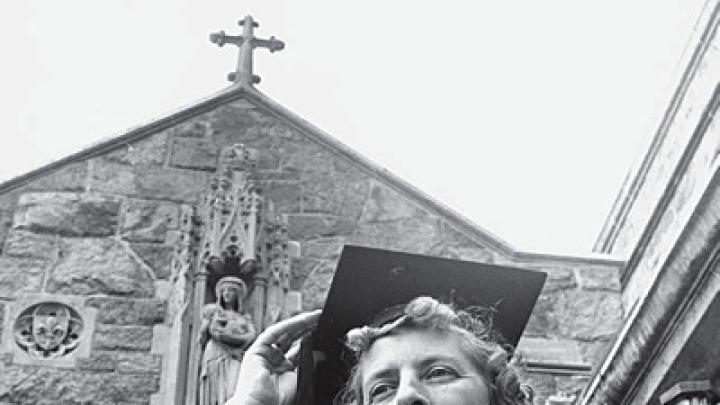

It would take 60 years, and many ups and downs in the life of the Divinity School, for the alumni proposal of 1893 to be accepted by the Harvard Corporation. But at the convocation of 1955, eight remarkable women joined the ranks of HDS students.

At that convocation, the newly appointed dean, Douglas Horton, chided the school for its tardiness in admitting women by remarking at the “mumbling and head shaking” that accompanied the admission of Anna Maria Shuman to study theology at the Frisian University in Holland 300 years before. He noted that Harvard Divinity School, in 1955, was adopting the thesis Shuman had developed in her seventeenth-century dissertation, that “the study of letters is becoming to a Christian woman.”

|

| "The question of the admission of women," Dean Willard Sperry wrote in 1949, "is sure to be reopened in the future …." |

| Harvard University Archives |

Horton himself had trained at the coeducational Hartford Seminary. Following the death of his first wife, he wed the 45-year-old president of Wellesley College, Mildred McAfee, a prominent lay leader in the Congregational Church. Many early HDS women students lived with the Hortons on the third floor of Jewett House. If any of them wanted a model for breaking gender barriers, Mildred McAfee Horton specialized in just that. During World War II, she had taken leave from her presidency to become the first woman commissioned officer in the U.S. Navy as director of its women’s reserve force, the WAVES. She excelled in electrical engineering, serving as the first female member of the boards of directors of both RCA and NBC. And she broke barriers in religion, where she served as the first woman vice-president of the Federal Council of Churches. Once, when asked her husband’s opinion at a committee meeting, she replied, “I really don’t know what it is. He is at home doing the breakfast dishes so that his wife can attend this meeting.”

In this environment the admission of women to the school could hardly be questioned. The dean’s report of 1955 states only that the Corporation had accepted the recommendation of the faculty. One suspects that the faculty might have recommended it long before that—if there had been one. But in the 1940s HDS had been a near-moribund institution, with a part-time dean and a limited curriculum delivered primarily by professors from the Faculty of Arts and Sciences (FAS). Interestingly, keeping women out merited more attention in the dean’s reports in the 1940s than letting them in did in the 1950s.

|

| Dean Douglas Horton welcomed the first women students to the school. |

| Harvard University Archives |

“The question of the admission of women,” Dean Willard Sperry wrote in 1949, “is one that has come up often over the past twenty-five years and is sure to be reopened in the future, particularly in view of their recent admission by the law school and the medical school.” Defending Harvard’s standards of excellence, he observed, “Most women divinity students devote themselves to the field of religious education, presumably proposing to become employed in Sunday Schools. We have no department of religious education as such, and there is at this moment no inclination to organize such a department, even had we the means to do so.” Further, he noted, “One cannot wholly escape the rather ungenerous suspicion that many a young woman enters divinity school with the unsuspected hope that she may become a minister’s wife.” “Whether or not women are going to be welcome and effective as parish ministers is not a problem which we can decide. That decision will have to be made by trial and error in the churches.” Sperry concluded, with remarkable candor, “I have no convictions and no wisdom on this matter.”

Whereas Eliot feared coeducation could cause poor marriages, Sperry feared it might lead to good ones, at least by the standards of his day. His comments recall the binary association of women with religious practice and men with religious ideas. Sperry’s dismissal of women’s place in theological education mirrored a view of the school’s mission as merely academic. HDS in his day offered no professional training in ministry, nor even academic training in the fields of theology or ethics in the modern world. The school was not viewed as having a transformative or leading role in religion or society, or even within theological education. It was not a place where new questions could be raised about the future or the past, or where the tools of critical inquiry could be used to answer them.

This latter view of the school, in which faculty members modeled intellectual innovation and its application in national and international conversations and professional contexts, would come to the fore in the 1950s, when HDS was reborn under the presidency of Nathan Pusey, the deanship of Douglas Horton, and the financial support of David Rockefeller. In 1955 women entered a school staffed by a youthful cadre of brilliant international scholars who felt the full support of their dean and president. They were inspired by the leadership of their professors in encouraging a social role for the churches, as well as by the faculty’s participation in the international ecumenical movement that would train a key generation of leaders in civil rights and social justice. But the women soon disappeared from the dean’s reports. Although Horton at least spoke appreciatively of wives of students and faculty who had formal roles in a number of school activities in the 1950s, in the 1960s women are not mentioned at all.

The school had done an about-face since the non-activist days of the 1940s. New departments of theology, ethics, and comparative religion brought stringent moral analysis to contemporary social issues. The school conducted a colloquium in Washington, D.C., where students participated in a debate over black power between the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and the NAACP and attended congressional hearings on the Civil Rights Act. While a summer program began to encourage able African-American undergraduates to enter the ministry, a faculty report found that “white concerns, attitudes and habits” pervaded the life and curriculum of the school, and the Black Caucus, composed of HDS students, found even this self-critical report to be based upon “racist paternalistic assumptions.” HDS also courted controversy with conferences on sexual ethics and abortion. Harvey Cox published the proto-feminist Secular City in 1965 and Joseph Fichter, S.J., the Stillman professor of Roman Catholic studies, offered the school’s first course on “Women in the Church” in 1967, before praising fiery feminist Mary Daly’s 1969 book The Church and the Second Sex as “the most sophisticated, the most progressive, and the most honest of all the works that have attempted to deal with women in the church.”

Harvard Divinity School by all accounts was, in the words of one alum, “a happenin’ place,” yet it consisted almost exclusively of men, with no women on the faculty and only two or three graduating each year. Then, in 1970, the tide began to turn. Thirty-five women enrolled, almost as many as had graduated during the previous 15 years. The catalog of that year expressed a commitment to “encourage women to seek theological education, including preparation for the ordained ministry.” The next year, 56 women entered, with a critical mass of seven preparing for ordination.

The religious leadership of women was far more than a question of access to education. It required a curricular response, including a fundamental rethinking of the meaning of texts, doctrines, practices, and his-tory. The University’s first women’s studies program resulted. Proposed by a talented and astute group of women students who founded a Women’s Caucus, it found support from a sympathetic dean, Krister Stendahl, affectionately known as “Sister Krister” by the women. Stendahl, who became dean in 1968, had tak-en a pioneering stance in support of the ordination of women as a biblical scholar in Sweden, when the Swedish parliament voted to ordain women in the state church in 1954.

|

| Dean Krister Stendahl had supported the ordination of women in his native Sweden. |

| Harvard University Archives |

In the fall of 1971 the Women’s Caucus, consisting of women students, staff, and wives of faculty and students, began meeting weekly. Two students from the caucus responded to an assignment in Harvey Cox’s course “Eschatology and Politics” with a proposal to devote two weeks of the course to women’s liberation and to halt the use of the masculine pronouns “to refer to all people or to God” in class discussions. Cox submitted the proposals to the class and the 80 students voted to accept them both. The instructional budget paid for the kazoos that class members blew when they heard gender-exclusive language. “We chose kazoos because it made the class as a whole responsible,” one student recalled. “Nobody wanted to be the language police and everyone loved the phallic symbolism.” After undergraduate class member E.J. Dionne reported the story on the front page of the Crimson, Newsweek picked it up (December 6, 1971). HDS students, trained in the analysis of texts, rituals, and doctrines, were attuned to subtle and not-so-subtle repercussions of naming, classification, and symbolic action. When they turned their analysis to gender, the school would never be the same, and neither would the world.

That same term, women students invited Mary Daly to a dorm-room discussion of the invitation she had received to be the first woman ever to preach at Harvard’s Memorial Church. It was there that Daly, with the students’ encouragement, conceived the walkout from patriarchal religion that she led on November 14. When Daly descended the pulpit and invited others to join her in walking out, some Divinity School women followed her out of the church never to return, some followed her in an act of love and anger that would make it possible for them to walk back in on their own terms, and others remained inside, committed to using what they learned to reform institutions to which they remained loyal. Differences fueled passionate arguments among allies. Roman Catholic women studied together with women who could be ordained, those committed to ordination studied with those who rejected it as patriarchal, and those who came to the school to study religion but not to practice it confronted the value of faith in the lives of other students. “Somehow,” one student recalled, “what everybody was bringing was combustible.”

Lack of difference also proved to be combustible. The Women’s Caucus modeled itself on the Black Caucus. Participants were conscious of both the similarity of their agendas and the possibility that the groups could be used against each other. In 1971, women and African Americans each represented approximately 11 percent of the student body. One student has recalled that the Black Caucus was all male and the Women’s Caucus all white because there were no African-American women students at HDS. This was not quite true. The handful of black women who began to matriculate in the late 1960s usually identified more with their fellow black students than with other women, even though many black male students opposed the ordination of women. Bobette Reed Kahn, one of the first African-American women to receive the master’s of divinity degree, in 1976, had been the first black woman to graduate from Williams College, and would be the second ordained in the Episcopal Church. (After one year of doctoral study of the Hebrew Bible, she left Harvard never to return. “I loved the Old Testament,” she has said, “but I never wanted to be another ‘first.’ You have no idea how hard it is.”) Rena Karefa-Smart, probably the first African-American woman to earn a doctorate in theology, also in 1976, had been the first black woman to graduate from Yale Divinity School, some 30 years before.

During the 1970s, the percent of women students would increase yearly, until women were a majority by the early 1980s and stayed that way, while the percentage of African-American students leveled, and sometimes declined.

Dean Stendahl provided funds for a number of women students to travel to annual meetings of the American Academy of Religion, where they helped found the Women and Religion Section. A number of their term papers were published in anthologies produced by that group, including Emily Culpepper’s essays on menstrual taboos in both Leviticus and Zoroastrianism. Concluding that she could spend the rest of her life analyzing negative attitudes towards menstruation, Culpepper decided to explore the subject from a positive point of view in her M.Div. thesis. Graduation requirements called for either a private examination or a public disputation of the thesis. Culpepper chose the public disputation. Her thesis consisted of a 10-minute color film titled Period Piece, intended to provide an alternative to conscious and unconscious versions of President Eliot’s concern that a conflict existed between the demands of higher education and women’s “bodily powers and functions.” The Sperry Room was packed. One student recalled sitting between two professors who were chattering away in German, having forgotten that they had required her to learn the language. “My mother would roll over in her grave,” one said to the other as the film alternated images of women divinity students engaged in serious intellectual activity with images of those same students inserting tampons and performing self-examinations.

The dean’s report of 1972 mentions the first appointment of a coordinator of women’s programs. The position was part of the recently established office of ministry studies, where the first director, Patricia Budd Kepler, and most of her successors would be women. Excitement about pathbreaking women’s ministries enlivened the project of preparation for ordination. In response to proposals from the Women’s Caucus, Presbyterian clergywoman Alice Hageman spent a year at the school in 1972 as the Lentz lecturer on women and ministry, and together with students published Sexist Religion and Women in the Church: No More Silences, based on 14 guest lectures that took place that year.Pioneer feminist scholar Rosemary Ruether also came to HDS for a year on the Stillman Chair and offered the first course on feminist theology. Out of these experiences came a successful proposal from the caucus for what would eventually become the women’s studies in religion program.

|  |

| Four lectures open to women in the Greater Boston community, given in April 1959 under the sponsorship of the newly formed Women's Committee of the Divinity School, were well attended and enthusiastically received. | |

| Courtesy of the Harvard Divinity School | |

Initially the program brought five scholars to the school each year with the modest assignment of transforming the sources, methods, and conclusions of the fields of study comprising the curriculum. The initial student proposal, authorized by faculty vote on February 16, 1973, provided that “The group will be interracial in order to represent the experience of both Black and white women.” Not yet attentive to religious diversity, the program in its early years brought in a stream of African-American scholars, including formative figures in womanist theology, Jaqueline Grant and Katie Geneva Cannon. They helped attract a dynamic cohort of students who would make black women an important presence during the 1980s. Other early faculty members of note include historian Caroline Walker Bynum and Islamicist Jane Smith. In 1983, HDS tenured its first woman professor, theologian Margaret Miles, and Diana Eck, then professor of comparative religion and Indian studies [in FAS; now Wertham professor of law and psychiatry in society, master of Lowell House, and a member of the Faculty of Divinity], convened a conference on women, religion and social change, for which 70 women from around the world gathered at the Center for the Study of World Religions. In 1988, the feminist biblical scholar Elisabeth Schussler Fiorenza became Krister Stendahl professor of divinity, the first woman appointed to a named chair at the school. Today, a third of the HDS faculty teach and publish in the field of gender, many of them graduates of the school or former advisers or scholars of the women’s studies program.

Perhaps the most important lesson of viewing the history of our school through the lens of gender has to do with the intellectual benefits of being an outsider. If you feel like an outsider to this august institution, you are in very good company. Almost everyone I know feels like an outsider here, either because of their religious commitments or their lack of them, because of the particular background and vantage from which they approach the study of religion, their disciplinary commitments, their national origin, their race, or their sexual orientation, or all of the above.

|

| Notices of interest were posted on a special women's bulletin board in Andover Hall. |

| Divinity School Bulletin |

Participants in the Women’s Caucus wore their outsiderhood proudly: they trumpeted it from kazoos, displayed it on panels in the hallways, and projected it on the screen in the Sperry Room. Certainly the critical mass of women students enabled them to overcome the most painful aspects of isolation—their path may not, or may not yet, be open to all students. Yet their sense of outsiderhood enlivened conversations, fueled creativity, and engendered a profound level of commitment to the school. They proved many times over Virginia Woolf’s observation about the admission of women to British universities, that it is better to be locked out than to be locked in. This is a sentiment with which any intellectual can agree, but it has a particular salience for this school, which makes the audacious claim to study religion from a non-sectarian viewpoint, a mission that challenges us daily to consider the ways in which we may still be locked in.

Every religion accounts for gender as part of a created order, and we all live with the repercussions. Religion’s role in constructing, maintaining, distorting, and subverting gender is played out every day in headlines and in homes and schools throughout the world, in debates over birth control, abortion, and family violence that spill into both domestic and foreign policy, in debates about the Iraqi constitution and the American invasion of Afghanistan, about the nature of marriage, about health, law, development, and globalization. We at Harvard Divinity School have chosen to be actors rather than bystanders in this drama, by taking gender as an arena for critical investigation, rather than as a given. While we have much left to do, we pause today to celebrate what we have accomplished in this short half-century.

Ann Braude is senior lecturer on American religious history and director of the women’s studies in religion program at Harvard Divinity School. She is the author of Radical Spirits: Spiritualism and Women’s Rights in Nineteenth-Century America and the editor of Transforming the Faiths of Our Fathers: The Women Who Changed American Religion.