Jinhua, a prefecture composed of eight counties in the middle of Zhejiang Province—six hours by slow train south of Shanghai—is hot and wet in June and just plain hot in July. Still, getting 13 graduate students working on Chinese history, religion, and art history to spend a month doing research on local history in the field—instead of in the air-conditioned stacks of the Harvard-Yenching Library—turned out to be quite easy, and Harvard's Asia Center covered their costs. Earthwatch, which recruits volunteers from throughout the world to study the earth's cultural and biological diversity, also sponsored our trip, sending two nine-person teams that included architects, businesswomen, administrators, and artists.

|

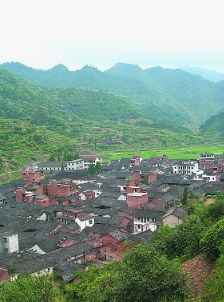

The village of Yuyuan, Wuyi County. |

Doug Skoniki |

Our purposes were multiple. We wanted to document groups of old buildings—the earliest dating to the fourteenth century—which had once served as the communal spaces for village, family, and religious life. Decades of rebellion and war in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the impoverishment of the countryside in favor of industrial investment in the 1950s, the massive destruction of everything old and private during the Cultural Revolution years (1966-76), and the building boom inaugurated by the new wealth of the 1990s have decimated traditional village architecture, which is characterized by multi-courtyard houses with whitewashed exterior walls and great wooden columns and beams supporting elaborate black-tile roofs. The three- and four-story semi-finished red-brick building is the hallmark of most Jinhua villages today. Some towns do care about preserving at least the best examples of what is left, but rarely do they get the financial support they need to restore and renovate what remains, and their own means are limited. We also hoped our presence would draw attention to a unique cultural legacy—at a moment when the pursuit of wealth leaves few people with the time to reflect on what is being lost—and support those local officials and villagers who are trying to save what they can.

|

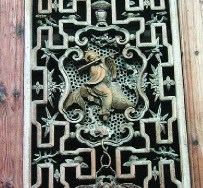

Detail of a lattice in Luzhai, an example of the sort of work for which the carvers of Dongyang gained national fame. |

Susannah Fone |

We wanted further to learn about the people who lived in and around these old buildings. I had begun research on local cultural history and settled on Jinhua as a case study in 1994, less out of personal interest than out of a conviction that the next generation of historians of China needed to see the local as part of the story of national history. Jinhua had one advantage over many other places: it had produced a number of literati who were at once locally active and nationally prominent, a combination that began to become important in the twelfth century. Like most of southeastern China, Jinhua has more written sources than one person can easily master even for the period I was most interested in, the twelfth through the fifteenth century. There are local histories for every county dating back to the twelfth century, hundreds of books by local men and (a few) women, and thousands of genealogies and family histories. And, as I was to discover, there is an artistic legacy: the remains of the great kilns that flourished into the fourteenth century, the painting and calligraphy of local artists, the portraits of ancestors, and the elaborate wood carvings that decorate structures built between the seventeenth and the mid-twentieth centuries.

But the idea of going to Jinhua itself did not at first appeal. A friend who had visited in 1985 found nothing but poor provincial cities and impoverished towns, with few historical sites well enough preserved to be open to the public. When I did decide to go, in 1998, it was more to get a sense of the landscape—Jinhua consists of several broad flood plains amidst the mountains—than with the expectation of learning much about history. However, two things had changed since 1985. First, the central government decided to allow the writing of the first local histories since 1949, and between 1987 and 1992 every county in Jinhua published a new local history, some more than a thousand pages long. Second, every county was told to identify the oldest historical buildings worthy of preservation. Thus in 1998, with a camera, a list of old buildings, and an introduction to a professor at Zhejiang Normal University, I made my way to Jinhua with a request to be allowed to spend a few days traveling around to see the oldest surviving buildings.

|

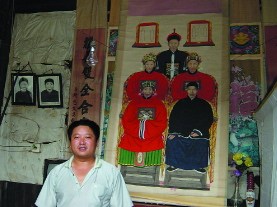

Chen Shouming at home, Zhiyan, Lanxi. The ancestor portrait is usually kept rolled up above the altar; he let it down for the photograph. |

Anna Lu Lane |

It was not until the third day of that trip, on a visit to Tower of Culture Village (Wenlou cun) in Yongkang County, that I discovered what the new local histories did not discuss. The old ancestral hall I wanted to visit dated back to the sixteenth century, to the time of Cheng Zi (1499-1586), a student of the great philosopher Wang Yangming (1472-1528), and of his son Cheng Zhengyi (1531-1610), who passed the civil-service examinations and became a high official. This time, instead of merely taking pictures of the building, I asked the inhabitants their names. They were all Chengs, descendants of Cheng Zhengyi. Within minutes they had brought out a newly published family genealogy, the first revision since 1949, and after that came portraits of their ancestors and an invitation to visit the family graves. It turned out that almost everyone in the village was a member of the Cheng lineage.

|

Beam structure and bracket carving in the Lu family compound, Luzhai, Dongyang. The county retains a thriving building and carving industry. |

Elizabeth Barrett |

At this point I stopped focusing so much on the old buildings and began to ask about the families who lived in them. The architecture of the county villages came alive: the buildings no longer appeared to be the residue of a bygone era—a traditional China that modernization is erasing—but an integral part of a dynamic society. As we have discovered, the Chengs were not unique. In every village, people are competing to update their genealogies, a difficult process since the Red Guards of the Cultural Revolution made a point of burning all the genealogies and ancestor portraits they could confiscate.

This year, we went to Jinhua with a mission: to create a visual record of buildings—through panorama and still photography and digital video—for a digital atlas, or GIS (geographic information system), of the research sites; and to learn as much as we could about the history of the social, cultural, and religious life of the villages and the lineages that had built them. Some of the sites, such as Luzhai in Dongyang County, were the compounds of great local families, now restored and treated as museums. Others, such as Zhiyan Village in Lanxi County, were poor farming villages trying to find the means to restore their ancestral halls and temples. Still others, such as Yuyuan in Wuyi County, were once well-to-do villages filled with old courtyard houses now refurbished with an eye to attracting tourists. Each site was different—in fact, once we began to make systematic comparisons, we began to see how great the differences in local architecture were—and each had its own history. In all of them the families welcomed us and our intrusive cameras into their homes and were extraordinarily generous with their time and with their historical records; in fact, our most unexpected expense was the cost of copying the massive genealogies loaned to us.

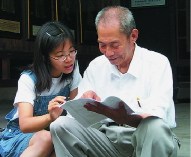

Our days began with a 6:30 breakfast, followed by a long and sometimes rough trip to a village. Eventually we figured out how to organize ourselves. First came an initial walk-through and introductions to local leaders. Then the mapping team would start on the most important or most interesting buildings. The video team would start to roam the streets. The GIS team would register the longitude and latitude of the town and climb a mountain to take overview shots. Two or three still-camera teams—a photographer and a note taker—would be assigned to photograph buildings systematically and the panorama team would set up for its shots. Two students would wander off in search of shrines and temples and the people who were responsible for rebuilding them (usually elderly women who had been charged with this responsibility in a dream), and everyone else would begin interviewing the village leaders and elders. But sorting and archiving photo documentation, knitting together the panoramas, typing up interview notes, scanning maps, and backing up all the computers kept us busy until late at night. We all learned to sleep on the bus.

|

Roof lines, Luzhai in Dongyang. |

Susannah Fone |

We also learned that what we saw was not a remnant of the past, but a revival of interest in the past. As the author of a newly revised genealogy explained, after the depredations of the Cultural Revolution and the recovery of prosperity, every town wants to update its local history and every family wants to update its genealogy.

But why? Our explanation goes something like this: During the first 40 years of its existence, the People's Republic of China sought to create a highly centralized state which would command the economy, define social status, suppress religion, break down extended kinship networks, monopolize culture, and control the distribution of wealth. From an historical perspective, this was a clear break in practice with the past: traditionally, despite the autocratic behavior of some emperors, the power of the central state and its local officials was matched by the ability of prominent local families to lead the community by building schools, sponsoring religious institutions, investing in local infrastructure, and defending their locale from lawlessness and banditry.

In southeastern China, the most successful of these families formed a local elite, intermarried, and prepared their sons for the extremely competitive national civil-service examinations; occasionally, one of the sons became an official. Their commitment to education as a means of rising in status (although it is clear that they invested in trade as well) created a stratum of local literati who gained local and sometimes even national fame as teachers, writers, philosophers, artists, and doctors. Essential to these families' survival was their ability to maintain different levels of community over extended periods of time. Ancestral halls provided the common space in which lineages and their various branches made offerings to their ancestors and placed the spirit tablets of the deceased; genealogies registered individuals' membership in the lineage; shrines and temples of local gods (the spirits of local men and women in many cases) provided a locus for community worship; clan schools provided a basic education and private academies schooled a smaller proportion of young men in high culture. All these institutions came under attack by the People's Republic precisely because they impeded the government's effort to create a state in which everyone's primary loyalty would be to nation and party.

|  |

Graduate student Chen Wen-yi interviews an elder of the Lu family, part of the committee that updated the family genealogy. | Peter Bol confers with the younger Lis, Lizhai, Dongyang. |

Susannah Fone | Susannah Fone |

What is happening today in many places throughout China is a recovery of a degree of local independence, space in which lineages and communities can gain some degree of autonomy—sometimes with the support of local governments, and sometimes against their will. In the countryside in particular, the forms of community that villagers themselves can construct, independent of the state and party, are those that existed before 1949: the lineage, with its genealogies and ancestral halls, and the shrines and temples of local gods. Every lineage we visited was updating its genealogy, if it had not already done so. Some of them were even building new ancestral halls (now called "memorial halls" to circumvent the prohibition on building new ancestral halls) and "taking back" shrines and temples that were destroyed to avoid the prohibition on building new religious sites. We should not expect families to build great wooden and stone houses, instead of the cheaper brick and cement "Western-style" houses of today, but it did not take us long to discover that the grand new four-story buildings that at first looked so out of place in the countryside were, in fact, the contemporary version of the great houses built by successful lineage members in the past. The difference is that, in place of the traditional horizontal extension, there is a vertical extension, with separate apartments, rather than separate courtyards, for the descendants.

There is a China of great urban centers, like Shanghai and Beijing, that already rival the great cities of Japan, the United States, and Europe. But our summer's work in Jinhua reminds us that there is also another China, a place less familiar to us, that is no less vital and no less interesting.

Peter K. Bol is Carswell professor of East Asian languages and civilizations. He is also serving a three-year term as a director of this magazine, nominated by the dean of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences. The material gathered during his recent trip will eventually become available on the website of a new course on the past thousand years of Chinese history as seen from the local perspective.