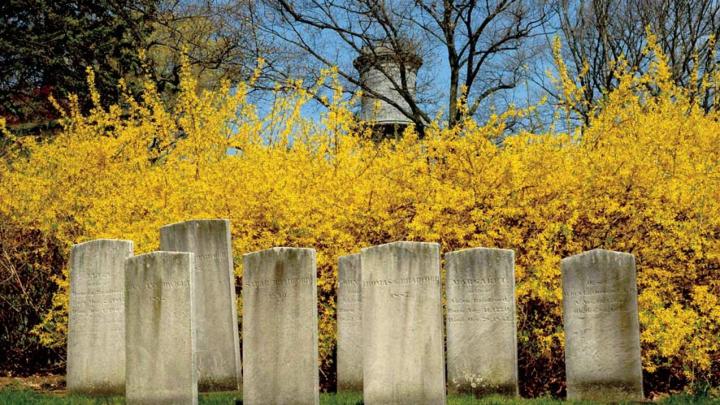

In April and May, birders flock to Mount Auburn Cemetery. Dressed in fleece and caps, binoculars slung around their necks, they enter by the Egyptian Revival gateway at 7 a.m., and spread stealthily across the sculpted 175-acre landscape. Winding pathways and grassy knolls lead to Halcyon and Auburn Lakes, or to the wooded Dell. Water and the flowering shrubs and trees attract thousands of migrating birds to this urban oasis each year. The birders’ hopes of hearing them, if not seeing them, rise with the sun.

Nestled in the arms of a copy of Lorenzo Bartolini's 1833 statue, Trust in God

Courtesy of Mount Auburn Cemetery

Red-winged blackbirds. Grackles. Scarlet tanagers. Baltimore orioles. Eastern phoebes. All of them are fairly common, says Jeremiah Trimble, assistant curator in the ornithology department at Harvard’s Museum of Comparative Zoology. He’s rambled through the cemetery since he was a boy, and currently leads bird walks on Thursday mornings through May 18. Rarer, he adds, are sightings of petite, jittery palm warblers, bay-breasted warblers, yellow-rumped warblers: “On a good day you can hear over 20 different species.”

Bird walks, formal and informal, occur almost every morning during migration season, but other visitors are drawn throughout the day to the cemetery’s historic arboretum and stunning array of plant life, especially as it’s emerging from a long, bleak winter. May brings flowering dogwoods, azaleas, and rhododendrons, along with weigela, mountain laurel, and Japanese snowbell. There are approximately 18,000 accessioned plants on the grounds, of which about 5,000 are trees, including 1,500 different conifers. Each year, the cemetery’s greenhouses also grow upwards of 32,000 annuals for planting in ornamental beds and within family plots. “The flowering trees and shrubbery have all the insects, which are what the birds are looking for,” Trimble notes, and lots of crevices for nesting. “Mount Auburn is just a very beautiful place to be in the spring.”

A common yellowthroat takes shelter

Photograph by Al Parker

That was always the point. Established in 1831, Mount Auburn Cemetery was at once a practical solution to Boston’s burial-ground crisis, and “the first designed landscape open to the public in North America,” says Mount Auburn’s curator of historical collections Meg Winslow. Boston’s population, spurred by increasing industrialization, had grown enormously by 1825, and even its cemeteries were overcrowded, she explains: “They were burying so many bodies that you might come upon bones and coffins sticking out of the ground.”

Yet Mount Auburn’s principal founders, Henry A.S. Dearborn and physician, botanist, and Harvard professor Jacob Bigelow, A.B. 1806, were leaders of the Massachusetts Horticultural Society. They seized the chance to develop an expansive “cemetery”—they were also the first to use that word, derived from the Greek “place of sleep,” Winslow adds, instead of “graveyard”—on a hilly rural property that would double as a place where people could escape the rising congestion of urban life. The men and their supporters (including then-Boston mayor Josiah Quincy III, A.B. 1790, who would become Harvard’s president) envisioned a tranquil landscape with ornate gardens, sculptures, funerary art, grand monuments, lakes, and exotic trees and plants.

As Bigelow wrote in A History of Mount Auburn, it was to be a sacred place, where “nature is permitted to take its course, when the dead are committed to the earth under the open sky, to become earthly and peacefully blended with their original dust…where the harmonious and ever-changing face of nature reminds us, by its resuscitating influences, that to die is but to live again.”

To receive curated picks of what to eat, experience, and explore in and around Cambridge from the editors of Harvard Magazine follow Harvard Squared.

To receive curated picks of what to eat, experience, and explore in and around Cambridge from the editors of Harvard Magazine follow Harvard Squared.

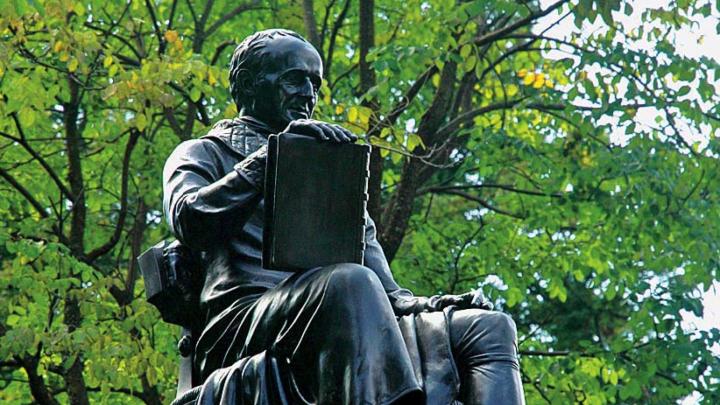

It was a major success. By the 1840s, other rural garden cemeteries had sprouted up, and Mount Auburn rivaled Mount Vernon and Niagara Falls as a tourist destination. Today, this National Historic Landmark is the top Cambridge attraction on TripAdvisor, Winslow says, and attracts about 250,000 visitors annually. Many come to pay tribute to their loved ones, or to the luminaries buried there. The more than 98,000 interees include social reformer Dorothea Dix, artist Winslow Homer, art patron Isabella Stewart Gardner, behaviorist B.F. Skinner, Ph.D. ’31, JF ’36, S.D. ’85, and the essayist, poet, and physician Oliver Wendell Holmes, A.B. 1829, M.D. ’36, LL.D. ’80.

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, LL.D. 1859, “still reigns supreme as a well-known and beloved resident” who attracts visitors, according to Bree Harvey, vice president of cemetery and visitor services. Christian Science founder Mary Baker Eddy follows close behind. Her memorial, a white granite neoclassical temple on the edge of Halcyon Lake, was inspired by the Tower of the Winds in Athens, and required 34 marble carvers to complete in 1917.

The landscape has always inspired writers and artists. Emily Dickinson wrote about her visit in 1846, and local wildlife artist Clare Walker Leslie often sketches there. The Friends of Mount Auburn Cemetery, a nonprofit conservation group, has also begun an artist-in-residence program.

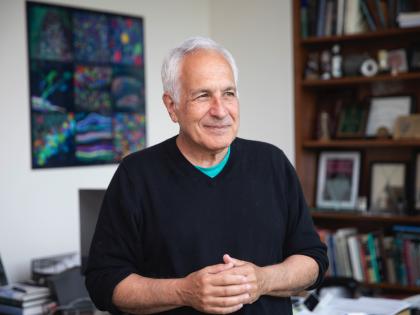

Artist Roberto Mighty

Photograph © Roberto Mighty

Inaugural artist Roberto Mighty, a filmmaker and photographer, began visiting the grounds in 2015, and this past February completed his resulting 29 short videos entitled “earth.sky” (viewable at www.earthdotsky.com). He describes the series as “a meditation on life, death, ritual, history, landscape, nature, and history.” The pieces spotlight the cemetery’s unearthly beauty, and offer insight into several individuals buried there.

A one-minute segment on Bernard Malamud (1914-1986), author of the Pulitzer Prize-winning novel The Fixer, features his tombstone inscription—“Art celebrates life and gives us our measure”—and former U.S. poet laureate Robert Pinksy reading an excerpt from Malamud’s 1984 address at Bennington College: “I don’t regret the years I put into my work. Perhaps I regret the fact that I was not two men, one who could live a full life apart from writing, and one who lived in art, exploring all he had to experience and know how to make his work right.”

Mighty highlights Soheyla Rafieezadeh (1954-2002) through interviews with her sister. Born and raised in Iran, Rafieezadeh moved to Boston for graduate school. She loved traveling, art, and the work of Iranian poet Forugh Farrokhzad, a line of whose “Let us Believe in the Beginning of The Cold Season” marks her gravestone: “Will I ever again dance on wine glasses; will the doorbell call me again toward a voice’s expectation?”

Artist-in-residence Mary Bichner

Photograph by Jen Johnston

The current artist-in-residence is singer, musician, and composer Mary Bichner. She’s composed 12 “classi-pop” pieces—about scampering chipmunks, bees and butterflies, the orbiting sun, seasonal changes—and performs them in live concerts at Mount Auburn on June 3 and November 4. The music will ultimately be released through the cemetery’s new phone app, she says, which will “allow visitors to listen to the compositions while in the settings that inspired them.” The first of six pieces in her Spring Suite, for example, is for a soprano and two altos, and expresses her experience of standing atop the cemetery’s highest point, the 62-foot Washington Tower, at dawn. (Visitors may also climb to the top for a panoramic view of Greater Boston.)

Views of Harvard and beyond from the top of Washington Tower

Courtesy of Mount Auburn Cemetery

Mount Auburn is likely the only cemetery in America to have such in-house artists, Harvey says. It’s also one of the few to encourage birding, and to offer a full plate of other year-round arts and educational events celebrating what Winslow calls “this very special community resource.”

A glance at the spring schedule shows:

- Satigatha Interactive Music and Chanting (May 7 and June 4). Buddhist and yogic songs, and devotional mantras and live music led by Harvard Divinity School friends Chris Berlin, M.Div. ’06, Darren Becker, M.Div. ’15, Alanna Cody, M.Div. ’18, and Andrew Stauffer, M.Div. ’18.

- “Memories of Mothers” (May 14), a walk with docents to explore funerary art symbolizing maternity and some of the prominent mothers buried there, such as writer and social activist Julia Ward Howe, author of the Mother’s Day Proclamation as well as “Battle Hymn of the Republic.”

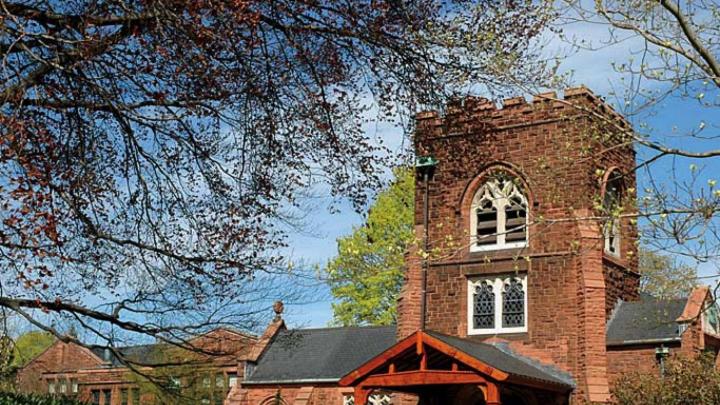

- Service of Commemoration (May 24) and Bigelow Open House (May 28). Both events are held in and around Mount Auburn’s first chapel, which was designed and built by cemetery co-founder Jacob Bigelow in the 1840s. (The chapel will be closed for renovations starting in July.)

- “Dances of the Spirit” (June 24). The New York City-based company Dances by Isadora performs Isadora Duncan’s “mourning” pieces.

Long before Mount Auburn was created, the landscape and farmland were “beloved” walking grounds for residents and Harvard students, including Ralph Waldo Emerson, A.B. 1821, LL.D. 1866, according to curator Winslow. Dubbed “Sweet Auburn” after Oliver Goldsmith’s 1770 poem “The Deserted Village,” the property had seven hills, woodlands and meadows, and ponds.

The rejuvenated Harvard Hill

Courtesy of Mount Auburn Cemetery

Just below Washington Tower is “Harvard Hill.” The 5,226-square-foot section, overhauled and cleaned up during the last two years, was donated to the College in 1833 by philanthropist and physician George Shattuck, A.B. 1831, M.D. 1835. Among the earliest burials were those of students such as Edward Thomas Damon, A.B. 1857, who was then enrolled at the Medical School. One of Roberto Mighty’s videos focuses on this 24-year-old, who died in 1859 after contracting smallpox—most likely from his work treating diseased patients quarantined in a hospital on Rainsford Island, in Boston Harbor. The chipped stone that marks his grave is inscribed: “This monument is erected by his classmates and friends.”

Not far away are the graves of renowned Harvard philosophy professors John Rawls and Robert Nozick (although the academic competitors might not have approved such close proximity), and of legendary professor and playwright William Alfred, Ph.D. ’54.

When Harvard Hill was donated, the new burial ground also reflected a cultural shift in views of mortality. The more punitive, Calvinistic approach to death as grim, as something to be feared, Winslow says, was giving way to the more romanticized notion of “eternal sleep.” Also influential in the cemetery’s design was the growing interest in the “picturesque” aesthetic (which would later inspire pioneering landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted). Many assume “that because Mount Auburn is a nineteenth-century designed greenscape, Olmsted designed it,” Winslow clarifies. “But he was a young boy of about 10 when the cemetery opened. Mount Auburn predated but set the stage for him and the entire American parks system.”

Jacob Bigelow was especially dedicated to the cemetery project, pushing it along for decades, and ultimately becoming the cemetery’s second president (after Joseph Story, A.B. 1798, an associate Supreme Court Justice and Harvard law professor). In the cemetery’s early years, Bigelow designed not only Washington Tower and Bigelow Chapel, but also the neoclassical Egyptian Revival gateway.

These principal structures set a visual tone of grandeur and gravitas, contributing to an overall design ethic rooted in English gardens and the Père Lachaise Cemetery, in Paris. The idea was to enhance the natural topography, balancing its inherent artistry with man-made sculptures, monuments, and other funerary art, according to The Art of Commemoration and America’s First Rural Cemetery, a booklet by Winslow and Melissa W. Banta, a consulting curator at the cemetery, and a curator at Harvard’s Weissman Preservation Center and Baker Library (see “Jolly Tippler,” May-June 2016, page 76).

The Sphinx is favored by children

Courtesy of Mount Auburn Cemetery

The Sphinx, sculpted by Martin Milmore in 1872, sits on the Bigelow Chapel lawn, and commemorates the Civil War. A model of it was transported from Milmore’s Boston studio by horse and carriage, and the statue was carved across the street from its final resting spot, from a 40-ton block of Maine granite. Another favored sculpture marks the grave of William Frederick Harnden (1812-1845). The entrepreneur developed one of the first express-package companies, but died of tuberculosis at age 31, Banta and Winslow write: “he’s buried next to his daughter Sarah, who had died two years earlier at the age of 10 months.” The granite, marble, and bronze monument consists of a base with a four-pillar canopy covering marble-slab gravestones and a Grecian urn, along with a life-size statue of an English mastiff, above which is inscribed: “Because the King’s business requires haste.”

“Everyone thinks they know about Mount Auburn Cemetery, but every time you come here you learn something new,” Winslow says. “And it’s a good place to meet, because as you walk through the landscape, you naturally talk about a wide range of topics—art and history, birds, and plants, death and life. We are so lucky to have this place.”

Some 2,000 people gathered for the cemetery’s consecration in September 1831. Joseph Story gave the address, according to Winslow, while still grieving the scarlet-fever death of his 10-year-old daughter:

….these repositories of the dead caution us, by their very silence, of our own frail and transitory being. They instruct us in the true value of life, and in its noble purposes, its duties, and its destination…As we sit down by their graves, we seem to hear the tones of their affection, whispering in our ears. We listen to the voice of their wisdom, speaking in the depths of our souls. We shed our tears; but they are no longer the burning tears of agony. They relieve our drooping spirits. We return to the world, and we feel ourselves purer, and better, and wiser, from this communion with the dead.

He died in 1845, and anyone can visit his grave, too. Lot 313, Narcissus Path.