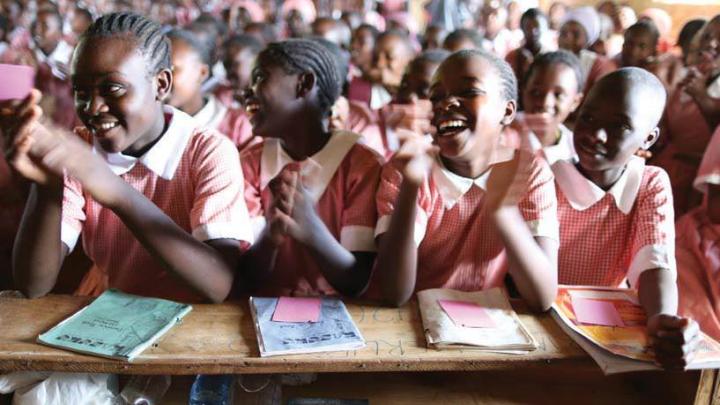

Megan white Mukuria ’99 is on a mission. The founder of the nonprofit ZanaAfrica Foundation works to promote awareness of an issue still taboo in polite conversation: menstrual health. Zana is the Kiswahili word for “tool,” and Mukuria started the organization in 2007 to give adolescent Kenyan girls tools they need to succeed: answers to their questions about reproductive health and sanitary pads. Today, ZanaAfrica Foundation distributes free pads, underwear, and reproductive health education to more than 10,000 girls a year.

The path to her mission was not obvious. Like many rising seniors, the cognitive-neuroscience concentrator “knew more what I didn’t want to do than what I did.” But that summer, she joined a group of Harvard and MIT students who traveled to Kenya to volunteer, and was placed with Homeless Children International–Kenya (HCI-K) in Kibera, an informal settlement in Nairobi. While helping girls who had just left the street transition to full-time school, Mukuria says, she realized “how truly some of these girls could be Harvard material, and how I could have ended up in their position if we had been placed in each other’s shoes.” That inspired her to think about how to help “break these girls out of systematic poverty,” on as large a scale as possible. Back at Harvard, she dropped her thesis to take classes in child psychology and Kiswahili. After graduation, she spent two years as a volunteer campus minister, but when she was asked to be HCI-K’s resource mobilization manager in 2001, she bought a one-way ticket to Kenya, and has been there since.

Working again with Kenyan girls, she began to realize that no one was providing them with information about reproductive health. The problem, Mukuria explains, was partly historical: traditional community rites of passage had been superseded by sometimes inadequate health education at school, and “the girls have kind of been lost in between.” The price of pads was an issue, too. As in many countries, and most of the United States, pads are taxed as a luxury item, like lipstick, and in Kenya this made them “the second biggest cost for girls every month after bread.” More than 65 percent of Kenyan girls don’t have access to them. Appalled by the situation, which caused girls to drop out of school at twice the rate of boys, Mukuria decided to do something about it.

ZanaAfrica’s approach reflects her experiences. The girls she worked with had many questions about their periods and reproductive health more broadly, so the foundation started by asking girls what they wanted to know, and built on that data, following UNESCO’s sexuality-education curriculum and consulting with the Kenyan ministry of health. The ZanaAfrica Group, the foundation’s social business partner, was set up to manufacture pads. The foundation now organizes health workshops during which it distributes pads; it is also at work on a monthly lifestyle magazine—to help girls understand their bodies and rights—as part of a research study, funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, to test the impact of delivering reproductive-health education coupled with sanitary pads.

Because its work remains sensitive, the foundation’s Partnership Program teams with local organizations in Kenya that have a direct relationship with schools in their communities, enabling ZanaAfrica to distribute pads and underwear and facilitate girl-centered reproductive-health lessons to students who need them. Its partner the Samburu Girls Foundation, for example, operates a rescue center for girls who are survivors, or at risk, of female genital cutting and child marriage; it also works to educate parents about the dangers of those practices. Girls’ and women’s reproductive rights remain an issue the world over, Mukuria says, and “part of the mandate of ZanaAfrica is that we feel we’re starting a movement” everyone is welcome to join. “One of the easiest things people can do” is discuss the topic among themselves, she adds: a simple conversation can go a long way toward ending stigmatization.

ZanaAfrica has won a Wharton Africa Business Forum Business Plan competition and three Gates Foundation grants. But for Mukuria, the most inspiring results are the personal ones. “When New Adventure School in Kibera called me and said that for the first time in their 13-year history, 100 percent of their girls had matriculated from seventh to eighth grade, that was incredibly validating—to see girls’ lives change so positively.”