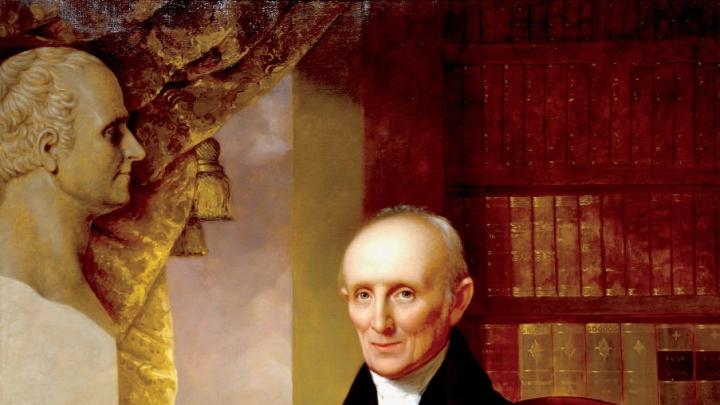

In 1816, Harvard awarded Nathaniel Bowditch an honorary doctor of laws, a decade after its (unsuccessful) offer of the Hollis professorship of mathematics and natural philosophy. These were remarkable moves, considering that Bowditch was entirely self-taught. But Bowditch was no less remarkable. He was the country’s most accomplished mathematician, the man Thomas Jefferson called “a meteor of the hemisphere.” Though remembered now largely for his New American Practical Navigator (1802), the ubiquitous guide for nineteenth-century mariners, he took much greater pride in his annotated translation of that apotheosis of Enlightenment quantitative sciences, Pierre de Laplace’s Mécanique Céleste.

So did his countrymen. For a young nation anxious to prove to Europe that it was not a cultural desert, this accomplishment would “be something to boast of,” wrote Harvard professor Edward Everett in 1818. Earlier Everett had complained that Europeans were barely aware of American scientific publications, noting that the only copies of Bowditch’s article on meteors to be found on the Continent were “the one my brother had brought in his trunk to Holland, and I in mine to Germany.” Citizens were therefore elated when in 1818 the Royal Society of London “paid a tribute to American genius,” as one Boston newspaper put it, designating Bowditch an honorary member of that august institution.

But why did he turn down the Harvard professorship? At the time, Bowditch already headed a marine insurance company in his native Salem, and unlike the Hollis chair, that post provided a generous salary and leisure to pursue his studies. He could hardly have doubted his ability to teach teenagers math and science (not until 1803 did the College add arithmetic to its admissions requirements), but he was haunted by his lack of a gentleman’s education, with its immersion in Latin and Greek. He was, one contemporary observer commented, afraid of “singing small on classic ground.”

Harvard tried again in 1810, seeking him as an Overseer. Once assured the “indispensable duties of the office” were minimal, he accepted. He assumed a far more significant role in 1826, when he was named to the Corporation, appointed this time for business, not mathematical, expertise. The College was in a financial mess and Bowditch, who had taken charge of a Boston trust and investment company, had a reputation for making it operate like a miniature solar system, a “great machine” running “with the regularity and harmony of clock-work.” Had Harvard’s powers-that-be known what he would do, they might have thought twice about their decision. “Order, method, punctuality, and exactness were, in his esteem, cardinal virtues; the want of which, in men of official station, he regarded not so much a fault as a crime,” Josiah Quincy reflected in his History of Harvard University, and when Bowditch detected such wrongdoing, he “would descend on the object of his animadversion with the quickness and scorching severity of lightning.”

Once Bowditch caught on to the loose, even negligent, way Harvard was run, the storm was not long in coming. College monies were mixed in with personal accounts, the books hadn’t been kept in years, and official papers consisted of “detached scraps” and shorthand “hieroglyphics.” President John T. Kirkland distributed scholarships without the Corporation’s knowledge or consent, awarded honorary diplomas against its explicit orders, regularly skipped chapel duty to dine with patrician friends in Boston—and then sought reimbursement for the bridge tolls. Bowditch set about cleaning house, social niceties be damned! Out went the College treasurer, the steward, and finally Kirkland himself.

Proper Boston was appalled, not so much by what Bowditch had revealed, or even by the results of his actions, but by the roughshod way in which he had conducted affairs. F.R.S. though he might be, Dr. Bowditch lacked the polished manners of the classically educated gentleman. It was all a “shameful business,” confided Charles Francis Adams in his diary. “But some men have no delicacy.” On campus, wrote Ralph Waldo Emerson, Bowditch “is sincere assafoetida”—a foul-smelling gum.

Eventually the Brahmins realized that Bowditch’s forthright ways had their uses. The patrician corporations he administered—financial, educational, and cultural alike—ran efficiently and profitably, and his willingness to offend powerful people had political utility. In maintaining the rule-bound Bowditch as a standard-bearer of their class, Brahmins promoted the notion that their institutions operated impartially, treating wealthy capitalists and poor folk with the same no-exceptions, clockwork regularity. When Bowditch received more European honors in the 1830s for his newly published Laplace volumes, elite Bostonians eagerly embraced this American Newton as a cultural ornament to the Athens of America.

Bowditch made no permanent mark as a scientist, but his methodizing, systematizing, rationalizing ways shaped American institutional life and the modus operandi of American capitalism. Harvard is a case in point. He left his Laplace manuscript to the College, and somehow it ended up at the Boston Public Library, sidelined like Laplacean science itself. But a numbering system for Harvard’s libraries? Printed annual reports of the President? That carefully managed endowment? Look no further than the Laplacean businessman on the Corporation.