Though snow may fall outside, inside their special exhibition galleries the Harvard Art Museums host some heat from desert Australia. Composed of 70 artworks—many of which had never left their native land before now—the exhibition Everywhen: The Eternal Present in Indigenous Art from Australia opened on February 5.

The project was some five years in the making for visiting curator Stephen Gilchrist, an associate lecturer at the University of Sydney, and its planning required many late-night conference calls. “I felt,” he jokes, “like I was calling from the future.”

That’s appropriate, perhaps, for an exhibition so interested in how people observe the passage of time. Most of the objects—including bark paintings, works on canvas, photographs, and sculpture—were produced within the past 40 years; they are shown alongside hair belts, woven baskets, and wooden vessels collected by Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology in the 1930s. Australian anthropologist William Stanner coined the term “everywhen” in the 1960s as a way to translate the Aboriginal experience of past and future as unified and overlapping: time is cyclical and circular, rather than unidirectional and linear, and the ancestral realm pervades the present. To express this concept spatially, designer Justin Lee shaped the exhibition’s floor plan like an unending figure eight. It was further divided into four thematic sections: “Seasonality,” “Transformation,” “Performance,” and “Remembrance.”

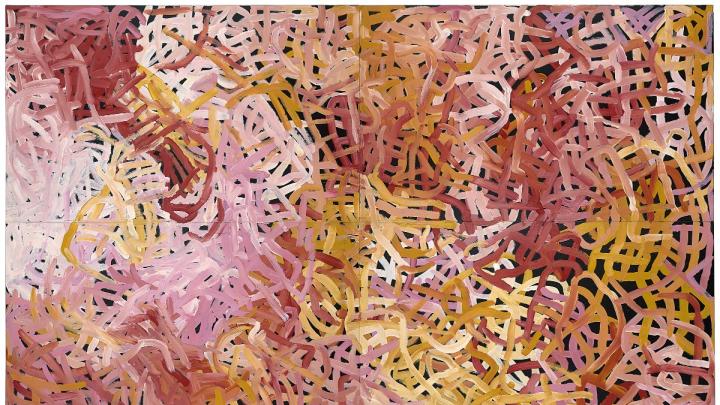

Visitors enter through “Seasonality,” which explores human relationships with the natural world and environmental transitions. Its gallery space is anchored by a four-paneled painting by Emily Kam Kngwarray, Anwerlarr angerr (Big yam), and by a trio of larrakitj, hollow log coffins for holding the bones of the dead, painted in earth pigments by Djambawa Marawili, Yumutjin Wunugmurra, and Djirrirra Wunungmurra. From memorial poles for the end of life, viewers can move on to see objects used at its beginning: the “Transformation” section displays coolamons, multifunctional wood vessels sometimes used to cradle babies.

Gilchrist selected these items from the Peabody in part to subvert what he considers the artificial divide between art and anthropology. As he puts it, “Art and practice are like hardware and software”: they make sense only when considered together. The curator also aims for the display to be a kind of “intervention” into the Peabody’s collections. Although museums typically recorded acquisition dates and collectors’ names for accessions, they often neglected to note the names of original owners or even makers. Placing the objects in their original context—their use by actual human beings—underscores a larger lesson: “You can’t have Aboriginal art without Aboriginal people.”

“You can’t have Aboriginal art without Aboriginal people.”

Other scholars are bringing the choices within artists’ work to light through scientific analysis of their innovations. In conjunction with the exhibition, researchers at the museums’ Straus Center for Conversation and Technical Studies undertook the first large-scale technical examination of indigenous Australian bark paintings. Across three years, the team collected 200 samples and surveyed 50 paintings, and traveled throughout Australia to interview artists about their methods. One focus was binders, the substances used to fix pigment to a surface. The earliest literature, from the late eighteenth century, claimed that bark paintings originated as temporary wet-weather shelter. As a result, scholars assumed that artists had not used fixatives until the 1920s, when a wider commercial demand for bark paintings created pressure to make them more permanent. But neither this conclusion, nor many suppositions about current artistic practices, had been scientifically tested.

“When we started, people said there was no binding agent,” recalls Narayan Khandekar, senior conservation scientist and director of the Straus Center. “They said, ‘You’re wasting your time, there’s nothing to find.’”

In fact, their research showed that binders were used far earlier, and more widely, than previously assumed. The conservation scientists detected binders in 77 percent of the samples, including in the oldest paintings examined, which dated back to no later than 1878. And though it was speculated that artists today used a number of different substances as binders—including beeswax and yolk from sea-turtle eggs—they found only two: orchid juice and bloodwood.

The conservators also analyzed the chemical makeup of the red, white, yellow, and black pigments (primarily derived from ochres, or earthen, mineral materials) used in traditional indigenous painting. In the process, they came upon a few nontraditional pigment sources, including blacks made from dry cell batteries, and silver pigment from two 1920s works that the researchers theorize came from the corrugated rooftops of buildings. Using two methods of trace element analysis, they will continue to study their samples, adding to what they hope will eventually become a larger, more comprehensive “atlas” of Australian pigments and trade routes. “There’s an awful lot to learn—we’ve just scratched the surface,” says Khandekar.

A few bark paintings can be seen in the exhibit, as well as works using traditional pigments and binders on canvas. Several pieces on display in “Performance” draw on iconography from indigenous ceremonies. These rituals are performed less and less often, Gilchrist explains in the exhibition catalog, but the artists express and transmit their ceremonial gestures and rhythms through the movements of their brushes, communing with ancestors and preserving traditional practices in a material form. In the exhibition, he says, “We wanted to reflect the Aboriginal beliefs not as mythology, but as reality.”

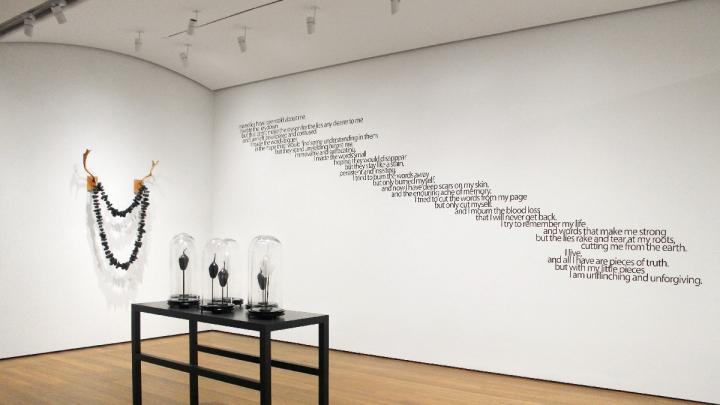

The section “Remembrance” grapples most explicitly with Australian colonial history. The black-and-white, blown-glass bush-fruits in Yhonnie Scarce’s installation The Silence of Others form her meditation on the hierarchies and taxonomies of race, especially in Australia, where aboriginal people were counted like fauna on an otherwise “empty” land, their bodies measured like specimens under scientific scrutiny. The rest of the art in “Remembrance” shares this restricted color palette: a digital image’s melting pixels, shiny acetate, the shadows cast on the wall by a sculpture’s jutting antlers. Such starkness not only draws attention to the variety of texture on display, but also serves as a kind of visual “palate cleanser,” suggests Gilchrist, clearing the way for the visitor to confront political issues.

“I don’t know what the color of memory is,” he says—though he notes that Judy Watson, whose painting bunya hangs elsewhere in the exhibition, says it’s blue—“but I wanted to strip away the inessential.”

Throughout “Everywhen's” stay at Harvard (until September 18, 2016), Gilchrist will open his biweekly gallery talks with a “Welcome to Country” or “Acknowledgment of Country” statement, showing respect to the traditional custodians of the land; the custom has been spreading at public events in modern Australia. The opening celebration to Everywhen on February 4 commenced with music from the didgeridoo (a long wind instrument), but even more startling than that instrument’s low, sonorous drone was what happened afterward. Gilchrist introduced members of the Mashpee Wampanoag Tribe and the Wampanoag Tribe of Gay Head (Aquinnah)—“on whose land the Harvard Art Museums stand,” he reminded the audience, eliciting a disconcerted chuckle—who then had the lecture hall stand for a prayer.

The Welcome to Country is, of course, a symbolic gesture, Gilchrist says: “Obviously there is no political outcome.” But in the realm of art history especially, he continues, symbols are important. Gilchrist, who belongs to the Yamatji people of the Inggarda language group, wanted to connect the experiences of Aboriginal people in Australia with those of indigenous people worldwide. In his view, the ritual may trigger a new awareness in museum visitors, making them see the gallery space as one in which “Aboriginal art, lands, and bodies are all sovereign.”

“Invisibility has been a precondition of indigeneity for so long,” says Gilchrist. Careful research and curation of contemporary art and older artifacts can help dispel the notion that indigenous people “belong to the past.”