Harvard today released the results of a sexual conduct survey taken at the University during the spring of 2015, and the results—echoing those from the 26 other private and public AAU (Association of American Universities) institutions that participated—are troubling both for the University and for higher education more generally in the United States. In a letter to President Drew Faust that was released in conjunction with the AAU aggregate report, former University provost Steven E. Hyman, who chairs the Harvard Task Force on the Prevention of Sexual Assault that was formed in 2014, called “the incidence of nonconsensual sexual contact by physical force or incapacitation…unacceptable” and said that it “requires concerted action from the entire community.” Among the most pertinent results Hyman detailed in his letter:

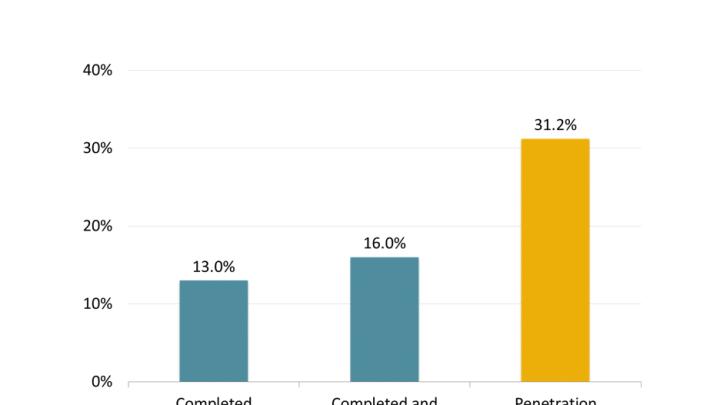

- 16 percent of female seniors in the College report completed or attempted penetration that was nonconsensual during their time at Harvard.

- When figures for nonconsensual touching are included, the above number rises to 31.2 percent.

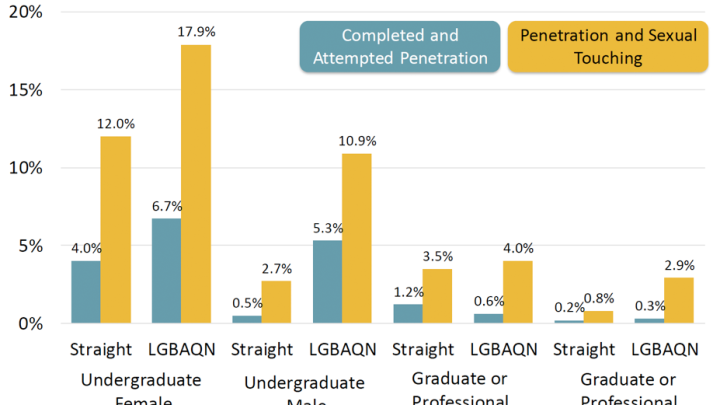

- Rates of nonconsensual penetration and touching are substantially higher among both men and women in the LBQAN (Lesbian or Gay, Bisexual, Asexual, Questioning and Not Listed) community throughout the University, particularly among men.

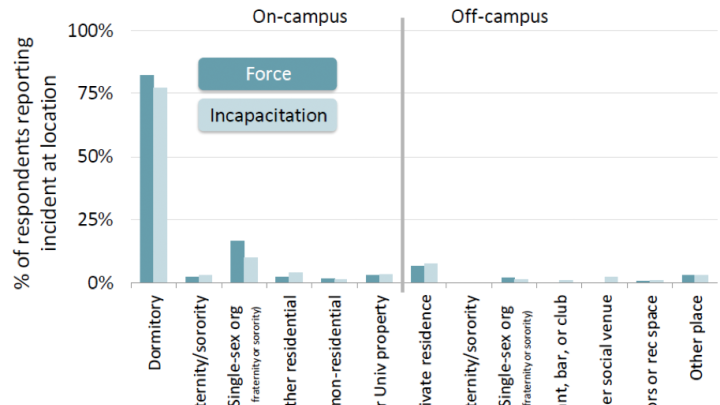

- While Harvard College females reported that the location where completed or attempted penetration most commonly took place (more than 75 percent) was in a dormitory, about 15 percent of incidents took place in single-sex organizations that were not a fraternity or sorority—final clubs and other club settings.

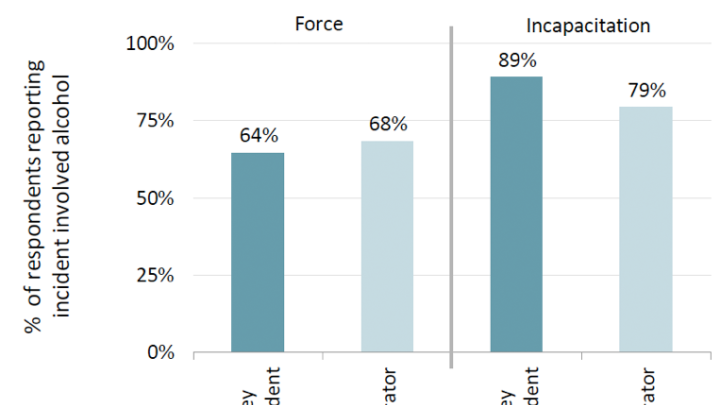

- Consumption of alcohol, either by the perpetrator, the victim, or both, played a role in the majority of incidents of complete or attempted penetration perpetrated by force, and for nearly 90 percent of the respondents who reported completed or attempted penetration by incapacitation.

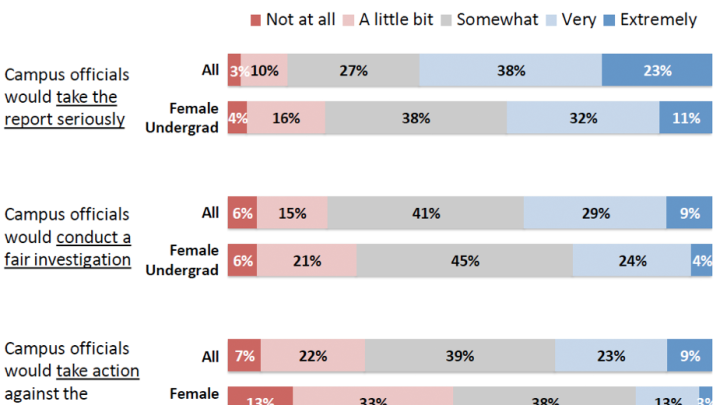

- Female undergraduates at Harvard are less likely to believe that campus officials would take a report seriously, conduct a fair investigation, or take action against an offender than the full set of students. Worse, only 16 percent of female undergraduates at Harvard believe it very or extremely likely that campus officials would take action against an offender, as compared to 37 percent of female undergraduates at the full set of AAU institutions surveyed, and 25 percent of female undergraduates at the subset of private AAU institutions.

These data buttress federal data that show that one woman in five is sexually assaulted while in college, a claim that had recently been called into question in the national press. The White House, which has been publicizing the one-in-five number, has taken an active stance against sexual violence on campuses by exerting pressure on colleges and universities through the Department of Education, The New York Times reported last year. The problem of sexual assault was brought to the forefront of discussion on the Harvard campus when The Harvard Crimson published “a long, anonymous, first-person account of an unwanted sexual encounter,” as reported at the time in Harvard Magazine. President Faust announced the formation of the task force headed by Hyman a few days later.

This morning, in a letter to the community, President Faust called the prevalence of sexual assault “a deeply troubling problem for Harvard, for colleges and universities more broadly, and for our society at large,” continuing:

These deeply disturbing survey results must spur us to an even more intent focus on the problem of sexual assault. That means not just how we talk to one another about it, not just what we say in official pronouncements, but how we actually treat one another and live our lives together. All of us share the obligation to create and sustain a community of which we can all be proud, a community whose bedrock is mutual respect and concern for one another. Sexual assault is intolerable, and we owe it to one another to confront it openly, purposefully, and effectively. This is our problem.

Only about one in 10 sexual assaults are reported, according to federal data cited by the White House; the Harvard survey indicates that 69 percent of female Harvard College students who indicated they experienced an incident of penetration by force did not formally report it, and neither did 80 percent of those women who experienced an incident of penetration by incapacitation. “The most frequently cited reason for not reporting,” Hyman writes in his letter, “was a belief that it was not serious enough to report.”

Surveys have therefore come to be seen as a key way to learn more about the scope of the problem on college campuses nationwide. Universities—reacting to government pressure and the threat of lawsuits brought by students under Title IX (the federal law that prevents discrimination on the basis of sex)—are therefore seeking more data so that they can figure out ways to increase reporting, prevent sexual misconduct, and comply with the law. (Harvard achieved a response rate of more than 50 percent in the recent survey, higher than any other AAU institution involved, thanks in part to the concerted efforts of administrators who even persuaded Conan O’ Brien ’85 to record a message urging participation.)

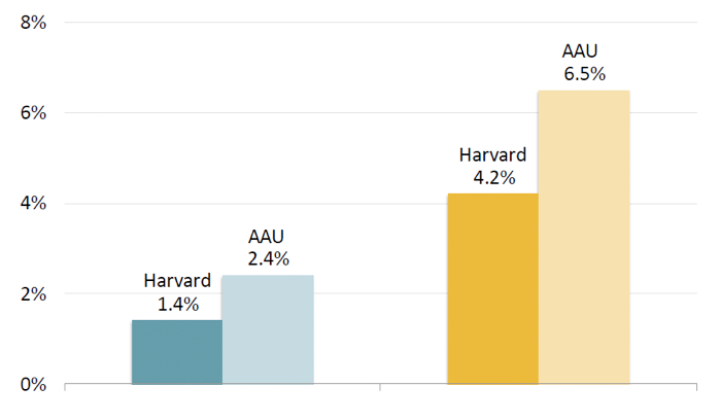

The data from the recent survey at Harvard show that the University overall, including the graduate and professional schools, had a lower rate of nonconsensual sexual contact than the AAU average in the eight months preceding the survey. But the reverse is true for the College, where Harvard’s numbers are slightly worse (i.e., higher) than for the average undergraduate student body among the AAU institutions that administered the survey.

Also disturbing is the lack of confidence in campus officials demonstrated by undergraduate women at Harvard: relative to the University-wide student body as a whole, they are less likely to believe that officials would take a report seriously, conduct a fair investigation, or take action against an offender. In fact, Hyman writes, “only 16 percent of female undergraduates at Harvard believe it very or extremely likely that campus officials would take action against the offenders,” as compared to 37 percent of female undergraduates across the AAU, and 25 percent of female undergraduates in private institutions.

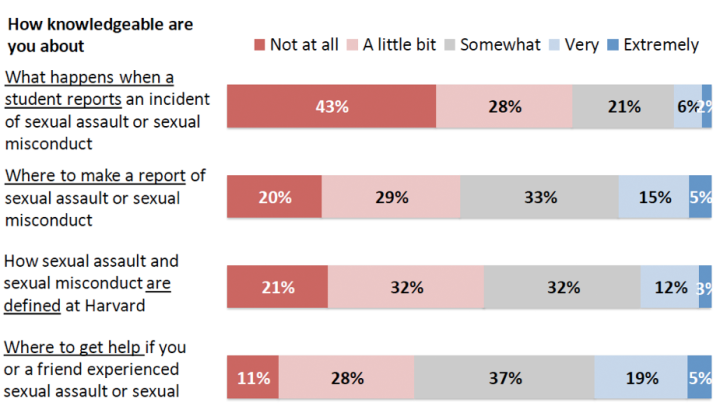

This lack of confidence in officials is matched by a paucity of student knowledge of University policies and procedures: about half or more of all undergraduate and graduate students said they knew little or nothing about what happens when a student reports an incident of sexual assault or sexual misconduct; where to make such a report; or even how sexual assault or misconduct is defined. More than a third said they wouldn’t know where to get help if they or a friend experienced such an incident. This lack of knowledge will doubtless be the focus of follow-up by Harvard researchers; the results suggest at the very least a profound need for better guidance and education.

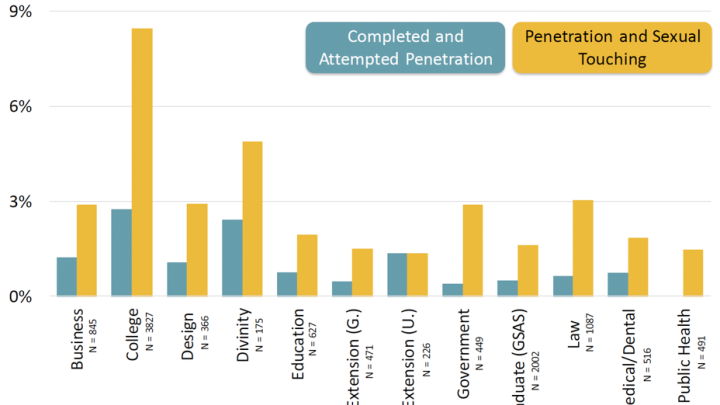

In her letter to the community, Faust pointed to several areas that “merit further exploration,” including the consistently higher rates of sexual assault reported by the BGLTQ community; the high correlation between sexual assault and the use of alcohol among both assailants and those who have experienced assault; the disturbingly low percentage of students who indicate they know where to get help or believe that the University will respond appropriately when assaults are reported; the activities that lead to assaults; and the locations where assaults occur, including the undergraduate Houses and freshman dorms as well as recognized and unrecognized student organizations. She has asked the task force to provide her with detailed recommendations by January 2016.

Faust also detailed some of the steps already taken: the adoption of a University-wide Title IX policy; the creation of the Office for Sexual and Gender-Based Dispute Resolution (ODR) to investigate reports of misconduct; the appointment of 50 [emphasis added] Title IX coordinators across campus; the doubling of staff at the Office for Sexual Assault Prevention and Response; the launch of a new web portal (Sexual Harassment/Assault Response and Education, or SHARE) to aggregate resources; and the expansion of orientation and training on sexual-assault issues. “Clearly, we must do more,” she wrote, seeking to engage the entire Harvard community:

University leaders—starting with the president, the provost, and the deans—bear a critical part of the responsibility for shaping the climate and offering the resources necessary to prevent sexual assault and respond when it does occur. But this challenge demands the insights and commitment of all of us—faculty, students, and staff—who are committed to building a community in which our care and respect for one another define who we are and aspire to be.

In the coming days and weeks, I want to hear your thoughts about what I can do, what you can do, and what we can do together to end sexual assault at Harvard. Meanwhile, I have asked the deans of each of our schools to present me with school-specific plans for community conversation, engagement, and action—drawing on the survey findings for their schools, on the ongoing insights of the Task Force, and on the many efforts they have already undertaken to engage their communities on this important issue.

For an account of the reaction from Harvard College students, please read the report filed by our former Steiner Fellow, Zara Zhang.