This round-up is part of Harvard Magazine’s series “At Home with Harvard,” a guide to what to read, watch, listen to, and do while social distancing. Read the previous selections, featuring articles about climate change, racial justice, movies and theater, and more, here.

Harvard’s vast library system is a source of endless inspiration and knowledge for students, professors, alumni, and those of us at Harvard Magazine. The libraries’ ever-changing contents and exhibits also make for beautiful and captivating magazine stories, from massive, world-famous Widener to tiny Houghton. The selections below cover noteworthy exhibits, resources, and reflections on the role of libraries themselves in an online world.

The U.S. Army's 24th Infantry Regiment, an African-American regiment, arriving at Camp Wikoff in Montauk, New York, 1898

Roosevelt Class No. 560.3, Theodore Roosevelt Collection, Harvard College Library, Harvard University

Bringing Black History to Light. “These voices that exist in our collections, they’re always just waiting for us to listen to them.” That’s what Houghton archivist Dorothy Berry told me earlier this summer about the vast new project she is leading, to digitize thousands of documents and artifacts relating to African American history. She and a team of Houghton colleagues—whose regular ongoing projects were put on pause when the pandemic shuttered the campus—will spend the next year researching, organizing, and scanning books, photos, pamphlets, personal papers, and numerous other items dating from the late 1700s through the early 1900s. Once everything is digitized, the material will be added to a website accessible not only to scholars but also to the public. The project itself is incredibly exciting, but I was deeply struck by the profound personal connection it has for Berry, who grew up in the Missouri Ozarks, living in the house her great-great-great-grandparents built, on land acquired from their onetime enslavers after Emancipation. Her childhood experiences with cherished family artifacts taught Berry what it means to be able keep those belongings handed down through generations, and also what it means to lose them. Those experiences have shaped her work, and they shape this project.

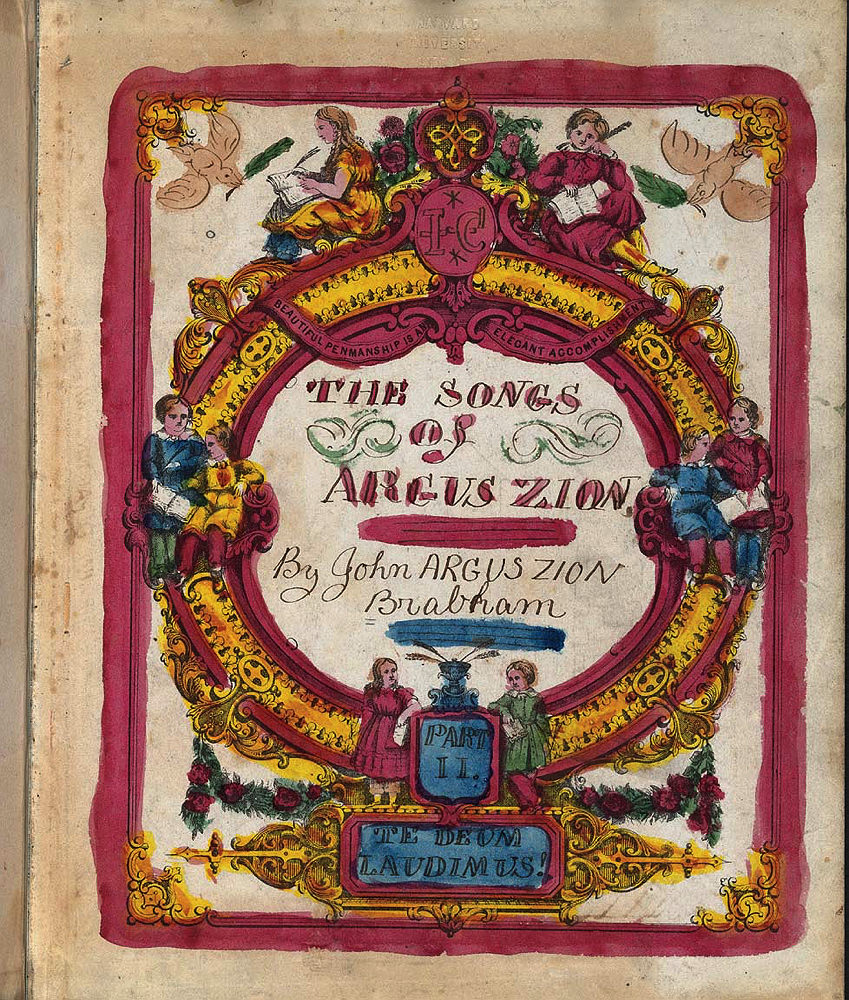

Journal from Houghton Library/Photograph by Harvard Library Imaging Services

Houghton Library, MS Eng 1610, vol. 2, frontispiece

The manuscript at the center of this delightfully weird story, “A Millennial Mystery,” sounds like fiction: a series of illustrated, handwritten journals, filled with visionary dreams, spiritual lyrics, and symbolic ciphers that may or may not map the way to a treasure chest of sealed revelations left behind by a nineteenth-century English millennialist prophetess. Part of the Houghton Library’s holdings, The Songs of Argus Zion is an unusual manuscript, and a persistent mystery. Writer Diane E. Booton dives into the vivid, enigmatic details.

An art installation designed by local architect Haydee Casellas sits in the center of “Passports: Lives in Transit,” created with glass plates and dozens of passports purchased by the curators on eBay.

Photograph by Brandon J. Dixon/Harvard Magazine

“Lives Glimpsed Through Passports,” by former Harvard Magazine Steiner Fellow Brandon Dixon ’19, gives a stirring glimpse of a powerful exhibit. “Passports: Lives in Transit” was on display at the Houghton Library in 2018 and told the stories of immigrants through the pages of passport booklets. “Those narratives reveal success and failure, migration and rejection, hope and frustration, and the fragility of a national identity,” Dixon writes. Curated by two graduate students who are themselves immigrants—one from Chile, the other from Argentina—the exhibit confronted the fraught politics of immigration and globalization. A banner at the entry read, “This exhibition conceives of passports as the ruins of a modern dream now in terminal crisis—the dream of a globalized world.”

~Lydialyle Gibson, Associate Editor

Portrait of Ruskin by Charles Herbert Moore

Courtesy of the Harvard Art Museums

In “John Ruskin, Victorian Radical and Art Historian,” I covered a small but delightful Houghton Library exhibit about “the foremost polemicist of the Victorian age.” This is an engaging look at the politics of the nineteenth century through the life of one man who helped shaped them. I wrote then: “Ruskin gave voice to the most radical responses to industrialism and inequality, and anticipated questions about labor, the environment, and the arts that resonate today.”

~Marina Bolotnikova, Associate Editor

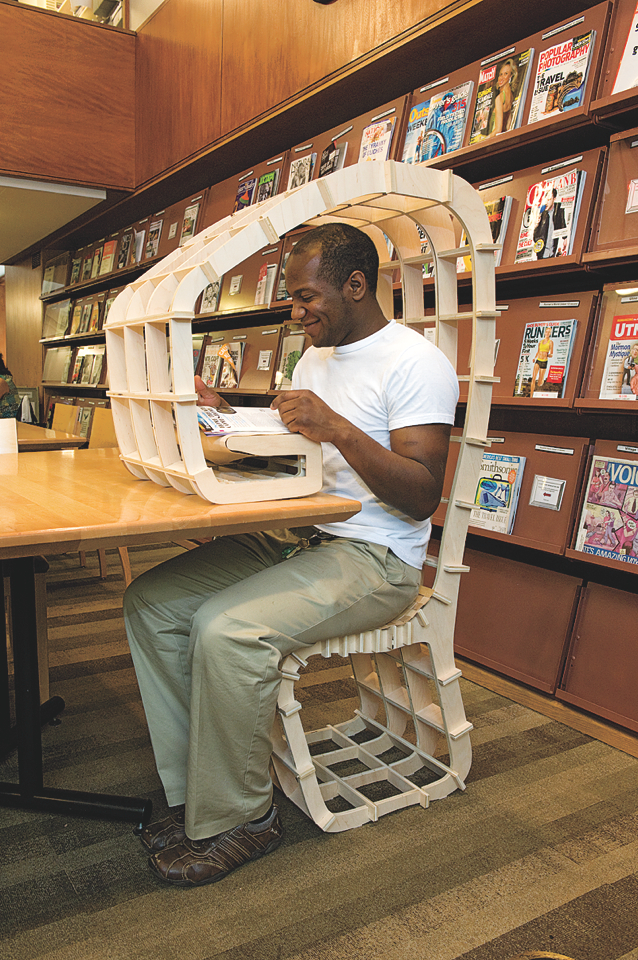

The Neo-carrel does triple duty as chair, laptop stand, and comfortable napping station.

Photograph by Jim Harrison

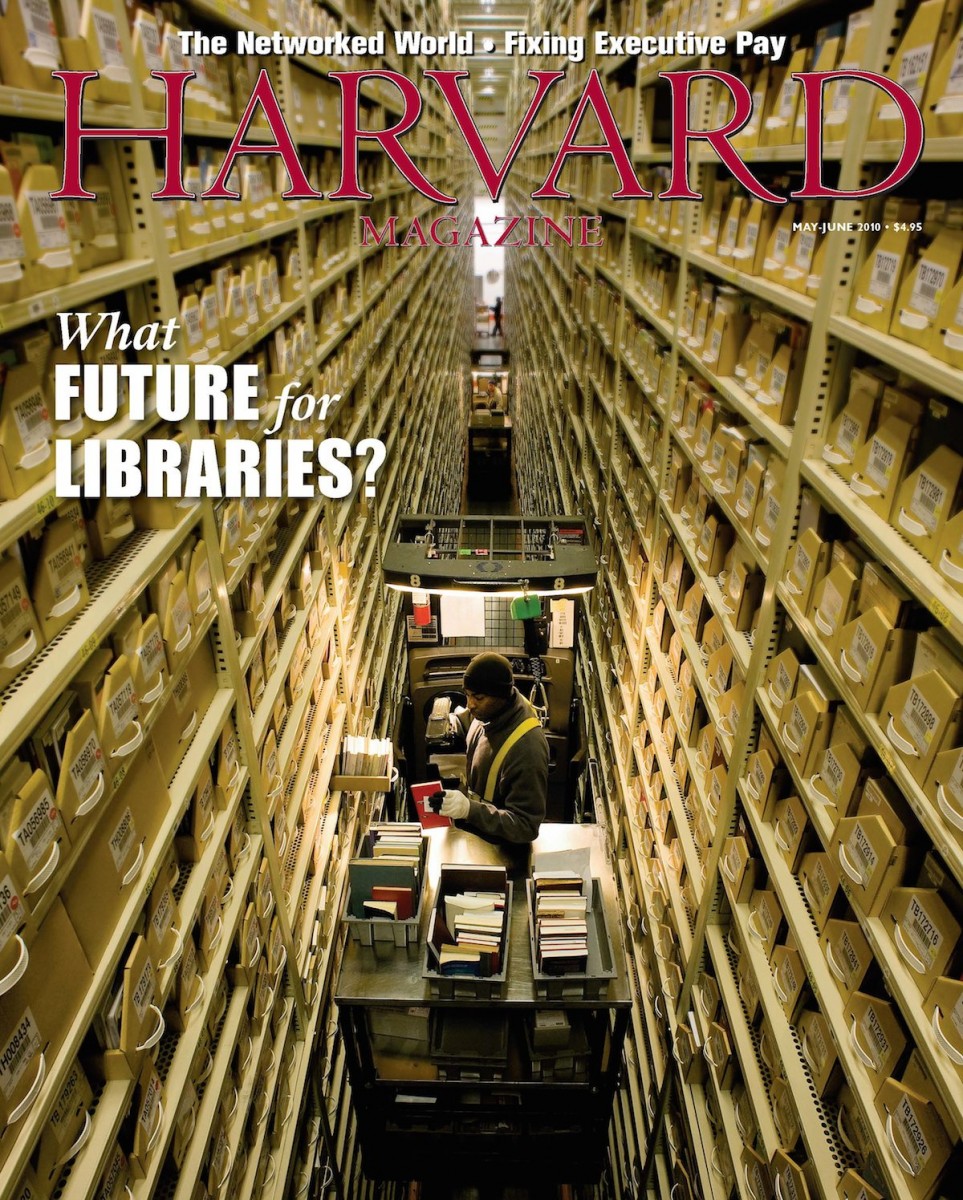

The Library Test Kitchen. If libraries are not just for books anymore, then what should they become? This is the question that Jeffrey Schnapp asked a class at the Graduate School of Design to consider in 2011. What services should a library provide? What kind of space do modern library users want? Schnapp, the Pescosolido professor of romance languages and literatures and of comparative literature, later chaired the faculty committee that provided input for the redesign of the Cabot Science library, a place popular with students pre-pandemic. The library was reconceived around spaces for making and doing. Abundant natural light, comfortable chairs, and the opportunity to purchase an espresso onsite are among the draws. Oh yes, and there are books.

As someone who loves lingering in libraries, browsing the shelves, it came as a shock to hear that some scientists find libraries full of books so useless that they compare them to museums. Knowledge, they say, is like a wave, and to be current, you have to surf off the front. That means reading the latest periodicals with cutting-edge research. And what of the books that contain specialized knowledge but are rarely consulted? Those now live in repositories, barcoded and arranged by size not subject, ready for rapid retrieval upon user request. This is the brave new world of knowledge curation described in Gutenberg 2.0.

~Jonathan Shaw, Managing Editor

Margaret Mee, Tabebuia umbellata, the yellow trumpet tree. Cult. São Paulo, Proc. Butantã, August 1964

Image courtesy of Dumbarton Oaks Rare Book Collection.

The Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, in Washington, D.C., is one of Harvard’s great humanities treasures: a center for scholarship on Byzantine, garden and landscape, and pre-Columbian studies. Under former director Jan Ziolkowski, Porter professor of medieval Latin, the institution extended its fellowship and internship programs, began commissioning new musical works, and, in important ways, augmented its exhibitions and outreach to the public and schools in its home community. A superb example of the latter—and a passion project of Ziolkowski’s, which put on display his formidable research prowess—traced a medieval European story, about a juggler who enters a monastery, and its many transformations and iterations through literary and cultural history, right up to modern resonances such as an American television version associated with Fred Waring (he of the Waring Blender fame), a staged version featured in Ebony, and an operatic interpretation by W.H. Auden (The Ballad of Barnaby), illustrated by Edward Gorey ’50. Sophia Nguyen put all these pieces together in “The Juggler’s Tale,” and a related sidebar conveys the experience of visiting the exhibition.

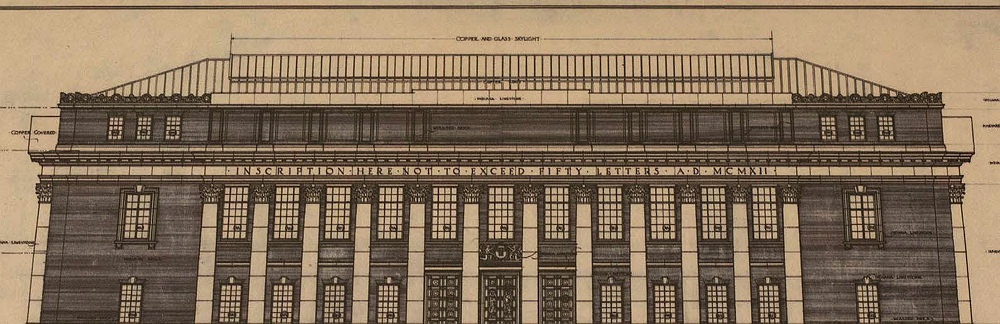

Photograph by Stephanie Mitchell/HPAC

Character Count. At a moment when Americans are coming to terms with the people excluded from or underrepresented within their national narrative, a small exhibition in Widener Library brought to light the overlooked role of Julian Abele, an African American architect, in designing that central part of the Harvard campus and determining some of its most cherished details. A single drawing from the exhibition, not definitively from Abele’s hand, nonetheless evokes the characteristics most associated with Widener—many of which can now more fairly be attributed to an unsung, and major, talent.

~John Rosenberg, Editor

I came into this piece knowing little about stolen library books. I’d heard that libraries were sometimes targets for theft, but I didn’t realize the scope and history of the illicit practice. This piece, by former (and beloved) editor Kit Reed, is a tour de force on the subject—deeply researched and vividly written. I’d recommend it for its engaging portraits of some of the most prolific book-stealers, and its analysis of the shifting ways in which libraries approach stolen books. Not only have security measures increased greatly over the past few decades, but librarians’ willingness to announce when a book is stolen or missing has also increased. Before, such an announcement was considered embarrassing, and few officials would bother informing the public when books were stolen. But as they found, it’s hard to find a book that no one knows is missing.

Why do professors love Widener Library and its stacks so much? Well, we can hear from them directly! These 12 personal essays from scholars across the University come from the Harvard Library Bulletin, and answer the question from former director of the Harvard University Library Sidney Verba: “How does one make Widener Library’s importance clear to those who do not already understand it?” The reasons vary widely, but are deeply felt in each.

~Jacob Sweet, Staff Writer/Editor

More from “At Home with Harvard”

- Spring Blooms: Your guide to accessing the Arnold Arboretum as the seasons turn in Boston

- Harvard in the Movies: Our favorite stories about Harvardians on screen

- The Literary Life: Our best stories about the practice and study of literature

- Night at the Museum: Our coverage of Harvard’s rich museums and collections

- Nature Walks: Walking, running, and biking in Greater Boston’s green spaces, even while social distancing

- Supporting Local Businesses: Our extensive coverage of local restaurants and retailers, and how you can support them during this time of crisis

- Medical Breakthroughs: Our best stories going deep into the ideas and personalities that will shape the medical care of tomorrow

- Rewriting History: From race and colonization to genetics and paleohistory, our favorite stories about the people reshaping the study of history

- The Climate Crisis: Highlights from our wide-ranging coverage of the environment

- Crimson Sports Illustrated: With 2020 winter sports ending early and the spring collegiate season wiped out almost entirely, we look back at Crimson highlights from past years.

- The Real History of Women at Harvard: Stories covering the admission of women, the Harvard-Radcliffe merger, the rise of women in the faculty ranks, Harvard’s first woman president, and more

- The Undergraduate: Our favorite student essays on the undergraduate experience

- The Secret Lives of Animals: From zoology and evolutionary science to animal-rights law to the joys of local wildlife, a selection of our favorite animal stories

- Harvard on the Small Screen: Our coverage of the creators, writers, and actors in your favorite TV shows

- Extraordinary Lives: From our “Vita” section, extraordinary profiles of authors, artists, activists, and more

- Great Legal Minds: Our favorite stories on the minds reshaping American law

- Harvard History through a New Lens: Some of our most notable stories about obscure, dark, or surprising episodes in Harvard’s history

- Health and Fitness: Our extensive coverage of Harvard’s breakthough health and wellness research

- Pride Month: Stories of Harvard's LGBTQ life, research and history

- Inequality in America: Stories of America’s extreme inequality

- The Immigrant Experience: A selection of our writing on immigration, displacement, and the global refugee crisis

- Harvard in the World: Harvard Magazine’s coverage of the University’s expanding global reach

- Theater & Broadway: Harvardians take to the stage.

- American Democracy: Our coverage of the nation's ailing democracy

- Traveling for the Story: Stories from all over the world